John Paul Vann: American Hero

John Paul Vann: American Hero

A lot of people wail that the age of heroes is long gone....

ONE SUCH MAN WAS JOHN PAUL VANN.

"The Age of heroes is not past....

so long as there remains ONE MAN

who contributes to sustain the weak,

mold the characters of the young

and bring hope to the lives of the needy."

We strongly encourage you to read the best book yet written on

the Vietnam war, A

Bright Shining Lie by Neil Sheehan and learn about this great human being.

John Paul Vann was a "mini-model" of America in her two Asian wars, travel

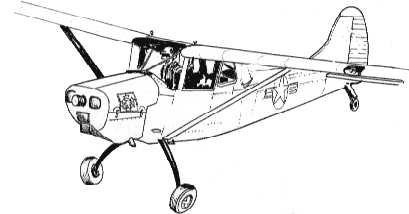

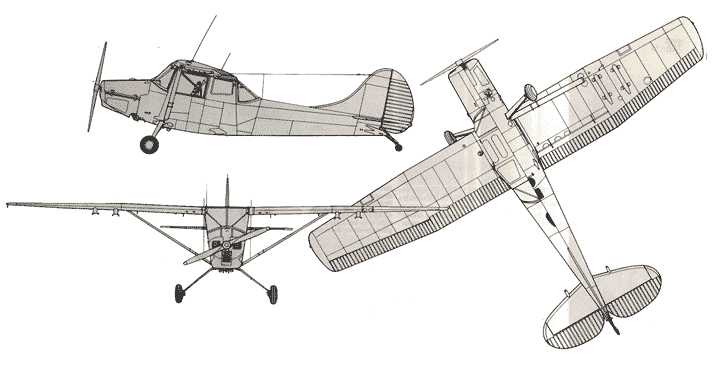

with him as a young U.S. Army officer he leads by example and personally drops ammunition from a L-19 "Bird Dog"

small plane to troops surrounded by the enemy in the Korean War.

SUB-NATIONAL CONFLICT #1: VIETNAM, THE BATTLE OF AP BAC

Follow him later as a LieuTenant Colonel (LTC), he advises the South Vietnamese Army at the 1963

epic battle of Ap Bac,

(scroll down after going to the link) again from a L-19 (O-1 Bird Dog) observation plane where a technical/tactical level of war pair of errors gives the VC their first victory against the U.S. war machines: the VC are operating a radio which a small plane direction finds locates; rather than run or disperse, the Viet Cong (VC) decide to stand and fight.

One of the easy-to-maintain, inexpensive fixed-wing STOL aircraft the U.S. Army used to operate before the rotorheads-for-everything crowd corrupted Army Aviation into its own branch off into their own little world

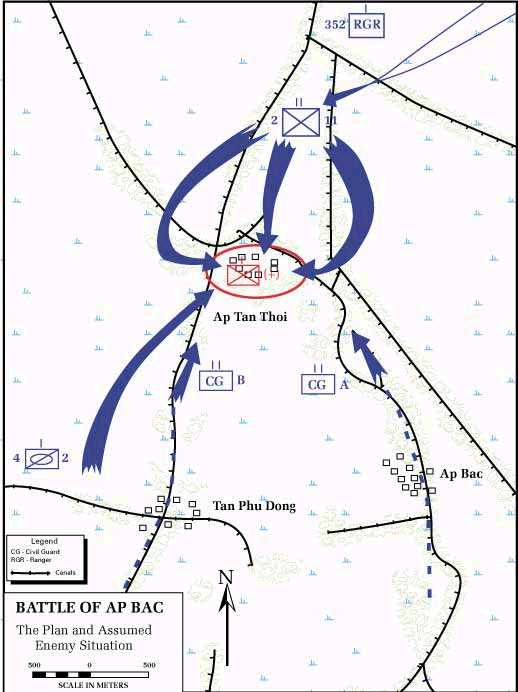

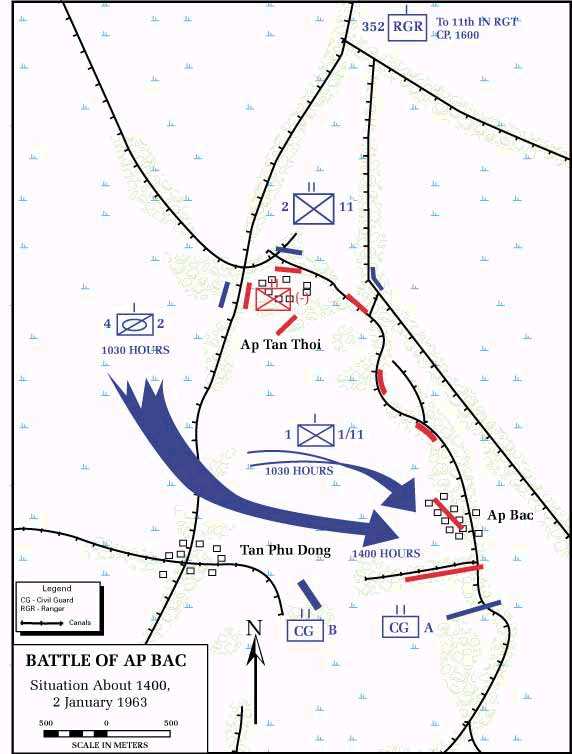

PLAN A: what we wanted to do and where we expected the enemy to be: Attack on Ap Tan Thoi village where the transmittor was located

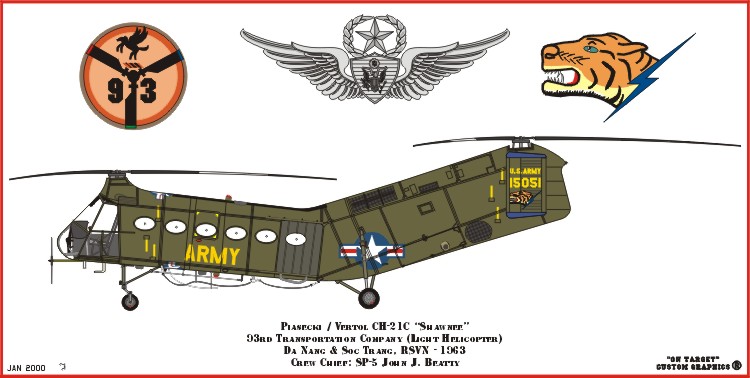

1/11th ARVN foot infantry flying by H-21 "Flying Banana" helicopters would land in the open rice paddies and converge on the enemy transmitter at Tan Thoi.

Unfortunately, the U.S. pilots flying the H-21 "Flying Banana" helicopters carrying the ARVN troops land within effective small-arms range (300 meters) of the dug-in VC despite Vann's radio instructions from the L-19 not to make that the landing zone (LZ).

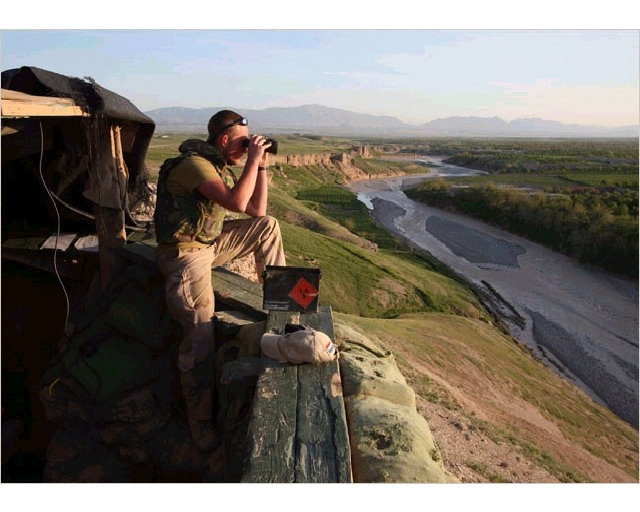

VANN'S VIEW OF THE LZ

Vann can clearly see from his L-19 that they are landing too close to the treeline, but the cocky American pilots don't heed his directions to land farther away.

ENEMY'S VIEW OF THE LZ

The picture above shows what the Viet Cong rebels saw as the H-21s landed; notice the Thompson .45 sub machine gun in the VC's hands...they opened fire concentrating in the exposed pilot's clear canopy area, killing several Americans and disabling 5 helicopters.

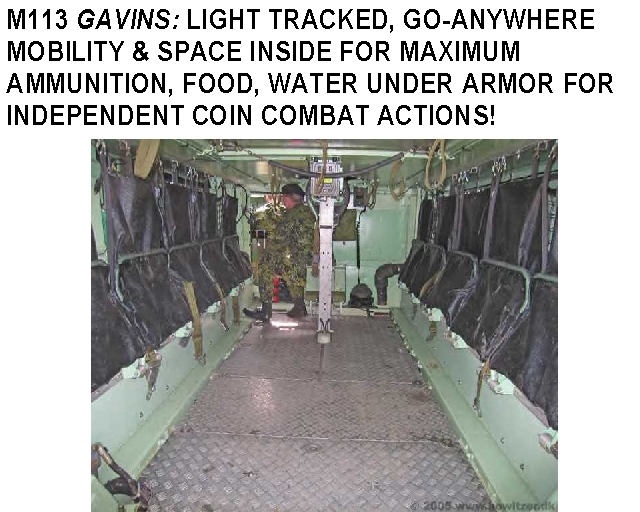

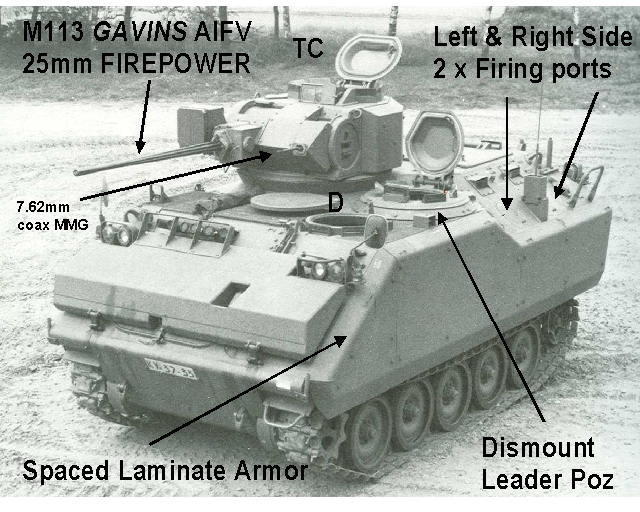

PLAN B: Vann orders 4/2 ARVN M113 commander, Ba to hurry up and drive to where the downed foot infantry force is clinging to its life and assault the VC in the treeline to the east. Ba is reluctant to use his M113s too aggressively as the President of South Vietnam, Diem expects him to use these armored vehicles to keep him in power from possible coups. Ba takes his sweet ass time to get to the scene.

With the helos shot to pieces, ARVN and American advisors wounded and dying, LTC Vann returns to base, gets in yet another small L-19/O-1 "Bird Dog" Grasshopper plane (Like Rommel and Patton, he knew how to fly) to spur the reluctant ARVN M113 commander to save the day and seize victory from the "jaws" of defeat.

What Vann saw from the air from his O-1 Bird Dog

However, the M113 force takes too long to get there by not having fascines to cross rice paddy dikes.

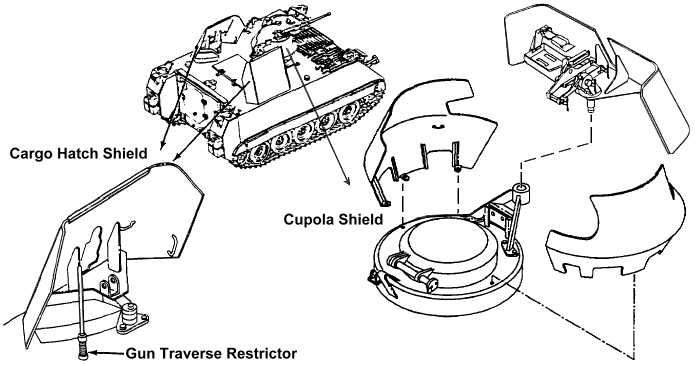

Ba's M113 Gavin light tracked Armored Fighting Vehicles (AFVs) do not have gun shields to protect their track commanders (TCs) manning their .50 caliber Heavy Machine Guns.

Thus, when the M113s arrive, the VC concentrate fire on the exposed TCs and they are turned back.

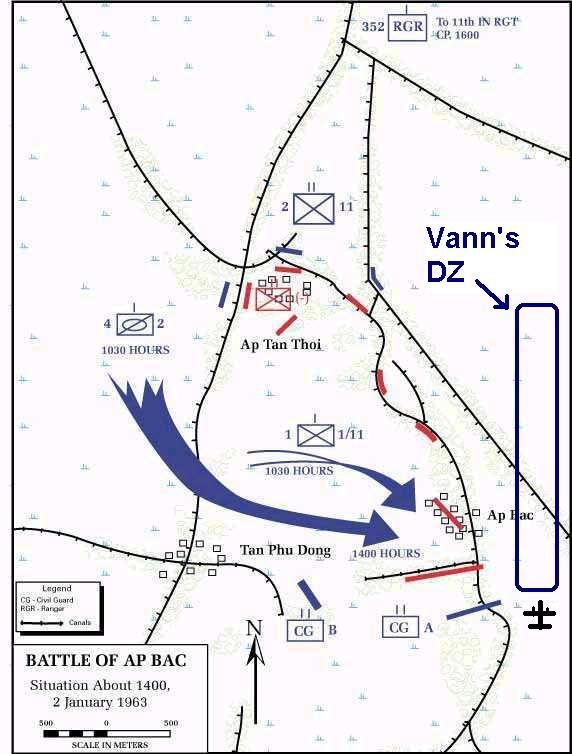

PLAN C: Vann flies back to base undaunted and gets the South Vietnamese Paratroopers ready to drop while he flies over with an American pilot in a borrowed L-19 to draw enemy fire and call in B-26 Invader air strikes.

Vann asked Porter to have Cao drop the paratroops in the rice fields and swamp land on the east side of Tan Thoi and Bac, the one open flank that the guerrilla battalion commander could not retreat across during the day, but that would become the logical escape route after dark.

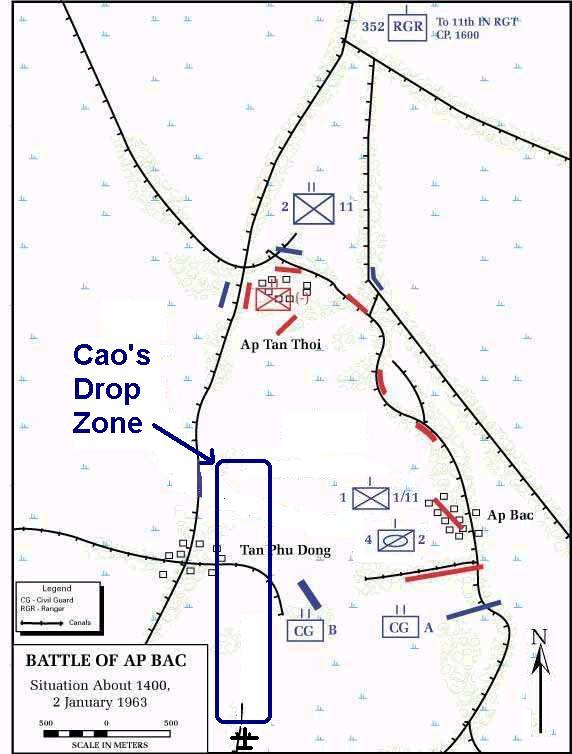

However, ARVN Paratroop commander Cao does not want to fight the VC, just land safely behind the Civil Guards and M113s as a "show-of-force". Sheehan continues:

"Topper Six, I've already told him to do that and he says he's going to employ them on the other side," Porter replied.If Vann had been commanding U.S. Paratroops he could have ordered them to drop behind the VC and even went up in his Bird Dog plane and personally guided the USAF C-123 transports to the proper drop zone (DZ). Since Vann was an "advisor" he can't make the ARVN fight and win if they didn't want to."I'll be right there, sir," Vann said, and instructed the pilot to return to the airstrip as fast as possible. He knew instantly what Cao's game was. As he was to put it in his after-action report for Harkins, Cao intended to use the airborne battalion not to trap and annihilate the Viet Cong but rather "as a show-of-force...in hopes that the VC units would disengage and the unwanted battle would be over."

Vann clambered out of the little plane and strode into the command-post tent. He told Cao that on this day he could not spend all of this blood for nothing. He had to close the box around the guerrillas and destroy them. Porter supported him, both of them arguing that Cao had no choice as a responsible commander. "You have got to drop the airborne over there," Vann said, poking his finger at the big operations map where it showed the open flank on the east side of the two hamlets.

He became so angry and was jabbing so hard at the map that he almost toppled over the easel on which it rested.

Cao would have none of this Soldier's logic. "It is not prudent, it is not prudent," he kept replying. It was better, he said, to drop the Paratroops on the west behind the M113s and the Civil Guards where they could tie-in with these other units. "We must reinforce," he said.

Vann was later to sum up Cao's logic with the tart remark: "They chose to reinforce defeat."

He lost his temper one more time. "Goddammit," he shouted, "you want them to get away. You're afraid to fight. You know they'll sneak out this way and that's exactly what you want."

Embarrassed at being driven into a corner, Cao pulled a huffy general's act on Vann, the lieutenant colonel. "I am the commanding general and it is my decision," he said. Brig. Gen. Tran Thien Khiem, the chief of staff of the Joint General Staff, who had flown down from Saigon at Cao's request and was present during the argument, did not object. Harkins had not come down to find out why an unprecedented five helicopters had been lost, nor had any of his subordinates appeared, so there was no American general in the tent to brandish his stars for Vann and Porter. Cao then attempted to mollify Vann by pretending to move up the drop time. He said, "We will drop at sixteen hundred hours"-4:00 P.M. civilian time. Knowing that it was useless to argue further and hoping that he might at least get a Paratroop battalion early enough to be of some use, Vann went back to his spotter plane.

He spent the rest of the afternoon asking when the Paratroops were going to arrive and attempting to persuade Cao and Dam and Tho to turn what was about to become the biggest defeat of the war so far into its biggest victory. They still had the opportunity to redeem the day. All they had to do was to pull the two Civil Guard battalions and Ba's company together for a combined attack on Bac. As demoralized as Ba's men were, they could have at least supported the Civil Guards with their .50 calibers, and the guerrillas could not have withstood the total force. Neither Cao nor Tho, who were the men in control, could see that the sensible and moral course was to press ahead and accept the further and proportionately minor casualties that would be necessary to give meaning to the sacrifice of those who had already been killed and maimed.

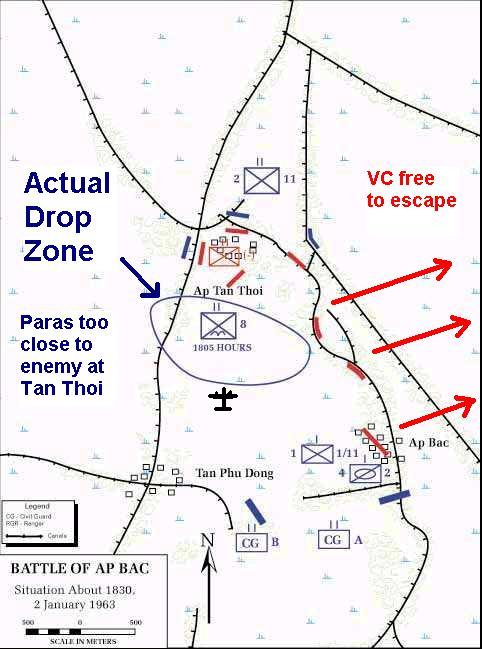

However, either the American C-123 flight leader or the ARVN Jumpmasters, initiated the drop on the west of Ap Bac too late instead of having green light begin at the southernmost beginning of the DZ; the ARVN Paratroopers landed too far north and west; in effective small arms-fire range of the VC at Tan Thoi, resulting in the two American "Red Hat" advisers getting wounded and a dozen of their men killed. Night fell and the VC escaped.

Paratroops dropped but inside forward line of troops instead of behind enemy route of retreat

The VC won despite their outnumbered odds because non-motivated ARVN officers refuse to launch a timely parachute assault to the VC's rear to trap them from escaping.

M113A3 Gavins now have gunshields for the TCs IF commanders are combat-oriented and not bogged down with garrison non-sense to order them...Iraqi Freedom's only Congressional Medal of Honor winner, SFC Paul Smith died in a M113A3 Gavin WITHOUT a gunshield kit; a hero who died needlessly from an U.S. Army and marine bureaucracies that don't even know their own history or studies the profession of arms...Look how long it took for gunshields to get back on top of vehicles after Soldiers began dying in Iraq in 2003!

M113A3 Gavins now have gunshields for the TCs IF commanders are combat-oriented and not bogged down with garrison non-sense to order them...Iraqi Freedom's only Congressional Medal of Honor winner, SFC Paul Smith died in a M113A3 Gavin WITHOUT a gunshield kit; a hero who died needlessly from an U.S. Army and marine bureaucracies that don't even know their own history or studies the profession of arms...Look how long it took for gunshields to get back on top of vehicles after Soldiers began dying in Iraq in 2003!

After Ap Bac, gunshields were placed on M113s like this modern A3 model has:

The loss at Ap Bac in 1963, emboldens the VC and the ARVN are routed continually thereafter when they try to fight the VC/NVA "even" rifle vs. rifle on foot; LTC Vann's Army career is destroyed as he is made the "fall guy" for ARVN corruption and incompetence.

The ARVN that wanted to fight effectively create the gunshielded M113 "ACAV" and their light mechanized infantry forces, though a minority---are the only bright spot in their force structure.

The situation deteriorates and this leads to the full-scale U.S. troop landings to fight off the VC from over-throwing the South, particularly the deployment of better Air Assault -trained U.S. Army 1st Air Cavalry Division troopers to prevent the nation being cut into two in the central highlands.

Maneuver Air Support Video: in praise of the O-1 Bird Dog

www.combatreform.org/airmobileAFACandMAS.wmv

www.combatreform.org/airmobileAFACandMAS.wmv

Unfortunately, America today has no manned, fixed-wing observation/attack planes like the L-19/O-1 Bird Dog to perform COIN/SASO operations correctly. What a travesty. Thank the fighter-bomber and rotor-head egomaniacs.

"Men don't follow titles........

they follow COURAGE..."

Mel Gibson as Freedom fighter, William Wallace in the film, Braveheart

What is so AWESOME about LTC Vann, is he doesn't give up! He makes countless briefings to those in power at the Pentagon to win the "hearts and minds" of the Vietnamese people, reform the South Vietnamese Army/government and not over-rely on refighting WWII in the rice paddies.

The recent film adaptation of Sheehan's book, A Bright Shining Lie starring Bill Paxton does a wonderful job of showing this. He becomes a civilian AID worker and he then goes about taking apart the VC infrastructure in the villages by Civic Action and fighting corruption. Vann networks---finds allies and leading-by-example makes it happen. After the Tet offensive gamble decimates the VC to nothing, the provinces are secure, though back home in America public support for the war has collapsed. Now for the Communists to win, The North Vietnamese Army (NVA); an external nation-state foe will have to invade. Which is what they do in 1972. The Army and marine generals now had a "WW2" type fight they longed for. Be careful for what you wish for...their FUBAR light infantry foot-sloggers from helicopters approach didn't work for them, and it certainly didn't work for the ARVN in 1975...

Before the 1975 collapse, in his finest hour, Vann gets in a helicopter and single-handedly directs air strikes and U.S. military/ARVN forces to repel the 1972 NVA invasion. One man can and did make a difference! NVA General Ngo Giap, victor at Dien Bien Phu, arguably one of THE greatest military generals of all time--no slouch himself, gets fired for this failure!

Sadly, Vann dies shortly thereafter in a helicopter crash. The state funeral he has opens Neil Shehann's AWESOME book which Oliver Stone should make into a movie. Our conjecture is that had Vann lived, the South would not have been lost to the Communists in 1975. He would have seen to it that people in Washington D.C. and the Pentagon would have not thrown away our hard-won victories in Vietnam. His loss was the turning point in the Vietnam War. He would have found a way to win because he was a PROFESSIONAL--not a bureaucrat.

JOHN PAUL VANN AS A METAPHOR FOR U.S. INVOLVEMENT IN VIETNAM?

Neil Sheehan in an extensive interview describing how he wrote his book said:

After all of this experience, both there and here, you chose this Colonel to focus on as a metaphor for American involvement. Why that choice?

He had influenced that band of war correspondents who first clued America in to what was going on in Vietnam during the last period of the Kennedy administration.

Oh yes, he'd influenced us enormously because his first year in Vietnam was during my first assignment as a reporter and David Halberstam's first American war assignment. Vann had an extraordinary mind. He had an incredible capacity to relate to human beings. He was a wonderful actor. He could manipulate people. He could sense human issues. At the same time, he had a capacity to deal with hard facts, like statistics. He was a statistician. Usually those qualities seem to cancel each other out, but they didn't in him. So in that first year, we were faced with the problem of covering a war where the advisors in the field were telling us we were losing the war. We could see that as well when we went out on operations, which was pretty frequent. The General in Saigon, a man named Paul Harkins, always saw the world through

rose-colored glasses and kept seeing it through them. He would maintain we were winning the war. You were caught between the two. It was an adversarial relationship. And Vann helped us to understand the war in a way that other advisors couldn't, because he was fearless. He would work down on a tactical level, and he could apply what he saw down there at the strategic level. He gave us perspectives and information that we didn't get from other advisors. He shaped our reporting because we were trying to come to grips with this ourselves, and this man helped us come to grips with it in a way we wouldn't have been able to without him."

Quantitative attrition/annihilation mentality:

We know one bitter Vietnam vet criticized the book, A Bright Shining

Lie, but needs to rethink his position: Vann is the model of the leader we need today who can network and orchestrate a victory on complex, Non-Linear Battlefields (NLBs).

To this may be added a further set of observations drawn from current events. Most adversaries that the United States and its allies face in the realm of low-intensity conflict, such as international terrorists, guerrilla insurgents, drug smuggling cartels, ethnic factions, as well as racial and tribal gangs, are all organized like networks (although their leadership may be quite hierarchical). Perhaps a reason that military (and police) institutions have difficulty engaging in low-intensity conflicts is because they are not meant to be fought by institutions. The lesson: Institutions can be defeated by networks, and it may take networks to counter networks. The future may belong to whoever masters the network form."

These guys are right-on-target at the source of our temporary loss in Vietnam 1975-1991?. However, war is not just a lethal sporting contest among combatants, its about whose IDEAS will dominate, in the case of FREEDOM, in the end the truth has won out over communism. It could have won out sooner at less human cost--had the U.S. military/industrial complex not been deliberately racketeering the conflict for greed/ego.

In fact, Sheehan returns years later to Vietnam in the book, After the War is over, Hanoi and Saigon a review states:

However, if the forces of freedom were more open-minded and networked like the Vann did while he was alive and the enemy did, we could have won the struggle sooner on the battlefield and not just wait for cultural changes to do it for us. The men who fought in Vietnam need to know that their sacrifices did count-just ask the people of Thailand. But if we are to learn from our war there, we must not make excuses that the politicians "did this or that" when there is plenty to do at our own level within the military to reorganize for better 2D/3D maneuver, network and "out-guerrilla-the-guerilla", which is what Vann did. We also have thanks to Ben Works of SIRIUS, the British example in "Imperial Policing" in the 1920s/30s and Malaya in 1950 to see what "right looks like".

Imperial Policing (entire book online)

John Paul Vann is one of the greatest American heroes to ever live, America's "Lawrence of Arabia" in the far instead of middle east; Sheehan's book is a classic, the major fault we have is the "lie" ending in the title, probably a sop to get anti-war types to read it! I would change the word to "Hope" that was lost that we need to rekindle by reading this fine book. Webster should contact Sheehan and have him write a sequel book to ABSL on the "missing" period of Vann's Vietnam adventures when he was Mr. Ruff Puff. Congressman Charlie Wilson was to Afghanistan what Vann was to Vietnam; but note both men did not get the chance to do the job right. Which is why we need a specialized Sub-National Conflict Stability Corps so the milbureaucracy doesn't racketeer and both SNCs.

SUB-NATIONAL CONFLICT #2: IRAQ, JOHN PAUL VANN COIN TECHNIQUES FOR TODAY?

COUNTERINSURGENCY: The John Paul Vann Model

In November of 1968, I can remember the legendary John Paul Vann speaking to our graduation class of newly trained advisors at Di An, South Vietnam. You can't win a guerrilla war by dropping bombs from the air, he said. You may kill some of the enemy, but you will alienate the people you are there trying to help, and they will turn against you.

John Paul Vann was our "Lawrence of Arabia" in Vietnam. He spent 10 years there, first as an American infantry officer, then later as the main architect of the Vietnamization/Pacification program.

Other words of his I remember were, 'You need to go after the guerrilla with a rifle at the village level and kill them face-to-face. And to do that effectively, you need local Soldiers from the area to assist you. If the locals are properly led and equipped, they will do the job.'

What Vann was saying seems to me to be applicable to Iraq today. You need the support of the local population and indigenous troops to combat the guerrillas/terrorists/thugs on their own turf. Large conventional American military infantry units aren't necessarily best suited for this task.

Most think that it was just the Special Forces who were conducting counterinsurgency (COIN) operations in Vietnam. Very few have heard about the Co Van Mis (Vietnamese for American Advisors) and the mobile advisory teams (MATs). After 1968, fewer than 5000 assisted, advised, and to use a recently coined term, were 'embedded' with a 500,000 Regional Force/Popular Force Army that took the war to the enemy at the local level for a period of over five years.

There were 354 mobile advisory teams made up of five U.S. Army personnel (two officers and three NCOs). The MATs were really a scaled-down Special Forces team with one of the NCOs being a medic and there was a Vietnamese interpreter for communication purposes. As a young lieutenant, I served with a number of Popular Force platoons and Regional Force companies while a member of Advisor Terms 49

and 86.

Very little has been written about this little known aspect of the Vietnam War. In the book about John Paul Vann and the advisory effort, A Bright and Shining Lie, the big lie is what the author, Neil Sheehan, leaves out of the book. Most of the book deals with the South Vietnamese Army and the advisory effort up to the Tet Offensive in 1968, and very little if any detail or mention is given to the many years afterward where the Regional Forces and Popular Forces gave quite a good accounting of themselves against the enemy.

Sheehan spends the first 700 pages of his book detailing how bad the South Vietnamese Army was up to the end of 1967 (parts of which are true), then spends several pages on the Tet Offensive in early 1968, in which he fails to emphasize that the main fighting units of the Viet Cong army including their commanders and NCOs were eliminated, never again to become a viable fighting force. Some interpret this sound defeat of the Viet Cong as a deliberate attempt by the Hanoi Leaders to eliminate their comrades in the south.

Sheehan then skips five years of the war effort where the Regional Forces/Popular Forces held their own against the NVA/VC and defeated them in most of the smaller unnamed battles of the war at the village level. Then he picks up again with the 1972 Easter Offensive where Vann was killed, not by enemy contact, but by a helicopter crash during the monsoon rains. Barely 30 pages of Sheehan's book are devoted to Vann's success with Vietnamization. There was hardly mention of the Regional Forces/Popular Forces [RF/PF] the home militias, the little guys in tennis shoes, who inflicted over one-third of the casualties against the enemy.

I spent almost nine months with these little guys as a lieutenant taking the fight to the VC at the hamlet and village level. Not all the RF/PFs were great Soldiers, but many of them were if properly led, just as Vann had told us at the advisor school.

Nicknamed the 'Ruff-Puffs', they were not configured to stand up against a large force of NVA regulars, but they could provide security for the locals in a hamlet or village. The Soldiers either had their families living with them, or in the nearby village. Who better to know when the enemy was coming into a village than those who lived there?

There were many times when I knew when the Vietcong were coming into the village at night to recruit or create havoc. And then instead of being ambushed, I and my little band of Popular Force Soldiers became the ambusher. We beat the guerrillas at their own game. We took the night away from them. We no longer patrolled endlessly and aimlessly looking for a needle in a haystack, waiting for the enemy to initiate contact.

We waited for them in the darkness of the night, and kicked hell out of them. In today's military vernacular, we preempted them. That's how you fight the guerrilla and the terrorist and beat him at his own game.

I cringe now watching news clips on TV as young American Soldiers in Iraq are ambushed by snipers and blown up with the new version of the command-controlled booby trap, the IED (improvised explosive device). But how would the young American Soldiers be able to distinguish the al-Qaida terrorist from a local Iraqi civilization? The simple answer is, they can't.

And how do they find the IED? The answer is they can't unless an informer warns beforehand as to the location.

I believe the answer to this problem is found in the type of force that Vann created in Vietnam, coordinated by CORDS (Civil Operations for Revolutionary Development Support). So different was this approach to conventional warfare tactics that Vann insisted it be operated under civilian control on equal footing with the military hierarchy. Vann really wanted the U.S. military advisors to be in command of the Ruff-Puffs instead of being advisors, but Robert Komer, the first director of CORDS, resisted this idea.

Vanns approach to counterinsurgency was the blending of all civilian agencies in Vietnam under CORDS with a loan of 1800 U.S. military personnel to serve as advisors to local Soldiers to provide security for all aspects of the U.S. effort in Vietnam. These were the front line guys who made up the mobile advisory teams, who moved from one RF/PF unit to another accompanying them on day and night time operations.

It seems to me we are always waiting for the enemy to ambush us in Iraq. The first strike is always thrown by the terrorist, and then we react by sometimes killing Iraqi civilians as the sniper fades away into the crowd. This unfortunate response is, in itself, a tactic of the terrorist/insurgent/enemy combatant.

Don't we need to pre-empt the terrorist as he is preparing the IED to blow up an unsuspecting U.S. Soldier and don't we need to know that a terrorist cell from outside Iraq has begun operating in a neighborhood? To do so, we need intelligence from the local civilians and Soldiers from the area who understand the language, customs, and dynamics of the local situation, who can easily point out strangers in the area even though they speak the same language, but look different.

The best of the MAT teams helped perform all of the above missions because they lived with their Vietnamese counterparts 24 hours a day, ate their food, got to know their families and developed friendships that last even today, 28 years after the war. The Co Vans did not retreat back to a secure base camp far removed from the people they were trying to help and defend.

So where do we get the local Soldiers in Iraq to perform this mission? As a former Co Van, I sat in astonishment when I saw the 500,000 man Iraqi Army being disbanded and sent home immediately after Saddam's main army collapsed. For the most part, they surrendered without firing a shot. Why send home a trained army, although obviously not well trained according to Western standards, but surely part of them could have been used along the guidelines of the MAT team concept in Vietnam?

I realize that all of Saddam's army could not have been used like we used the RF/PF in Vietnam, but surely some of them could. It was obvious that a large number of Saddam's conscripted forces were not loyal to him.

We could have had local Iraqi Soldiers patrolling under the command of small military advisor teams to help flush out enemy combatants and newly arrived in-country al-Qaida terrorists. The advisor teams would provide the coordination and communication with the larger American units in the area. This would enhance security for the civilian efforts and NGOs in Iraq. The Iraqi civilians must feel safe and secure before a new form of government can develop without the imprint of a terrorist stamp.

I believe that what Vann said in the 1960s in Vietnam is relevant today in Iraq as it relates to counterinsurgency. All the high-tech gadgetry and firepower that our military has today, leaves us relatively helpless when it comes to fighting the insurgent who blends in with the civilian population. An innocent civilian killed translates into a win for the terrorist. To avoid this, it takes the Soldier-on-the-ground with a rifle taking the fight to the terrorist, in an area that he previously thought was a safe sanctuary. And to do that, you need local Soldiers familiar with the terrain, the language and the customs of the area. John Paul Vann understood that.

The Vietnam Was has been mis-remembered, mis-understood, and mis-reported in regard to John Paul Vann's effort with Vietnamization and the fighting ability of the South Vietnamese Soldier. Sheehan has done them a great disservice in his book, A Bright And Shining Lie, from which a movie of like title was made.

Few know that the Viet Cong lost the war, and that they were no longer a viable force after 1968. The Viet Cong could not have won the war and bested the South Vietnamese Army in battle. The advisory effort in Vietnam wasn't perfect, but the South Vietnamese forces held their own in the 1972 Easter Offensive by the North.

The South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) was finally defeated in 1975 when they were invaded by the fifth largest army in the world. They were invaded by 17 divisions of the North Vietnamese Army to include over 700 tanks that steamrolled everyone in front of them. The North Vietnamese were still being supplied with war materiel by their allies, the Soviets and Chinese, while the allies of the South Vietnamese, the United States, abandoned them in their hour of need.

The ARVN were also disadvantaged and vulnerable because they had to defend everywhere, and the NVA could concentrate superior forces at weak points in the South.

The myth perpetuated by the anti-war media was that the South Vietnamese military was no good. I returned to the province capital of Xuan Loc, Vietnam, in 2002 and visited the large communist cemetery there filled with 5000 graves. This is where the last battle of the Vietnam War was fought, where the 18th ARVN Division defeated three NVA divisions before finally being overrun by 40,000 of the enemy.

Would Vann's model of counterinsurgency work in Iraq today? That's a good question, but what is the alternative? Our Soldiers now are getting tired, and our forces are being stretched too thin to continue the mission indefinitely.

The architect of the 1975 invasion of South Vietnam, North Vietnamese Tein Van Dung, in an indirect manner, gave Vann a complement for his conduct of the pacification program. In his book, Great Spring Victory, he never once mentions revolutionary warfare or the guerrilla tactics of the Viet Cong as aiding him in his final assault on the South. That's because Vann's program of Vietnamization had basically wrested control of the south from the guerrillas who we no longer

a viable fighting force.

That's rather ironic, isn't it? The myth exists today that peasants wearing rubber tire sandals employing guerrilla tactics won the war in Vietnam.

Our officials in Iraq are saying it will take three to five years to build an Iraqi Army. With Vann's model, we could have taken the best of the 500,000 former Iraqi military, and put them under the control of U.S. military advisors. Instead of having young American Soldiers patrolling the streets of Baghdad and the smaller cities around the country, surely we could have used Iraqi Soldiers advised by several thousand American military personnel. Instead, we sent them home to do what?

Unlike Vietnam, there is no outside Army that is going to invade Iraq in division-size strength and overwhelm our military units there. Our powerful and well-trained military units, with the aid of the British, have already won the big battles of the war. Now we need small units of local Soldiers taking the war to the enemy at the village level. I see no other way to preempt the terrorist before he has the time to act.

The small suitcase bomb, the suicide bomber, chemical and germ warfare, and the IED, all weapons used by the terrorists in the 21st century, make it necessary to defend everywhere. The terrorist will always go for the target of opportunity, searching for the most vulnerable target.

And this appears to be the difficulty of the are of the future the preempting of the terrorist before he can strike. Or, even before that, having the will and knowledge of how to preempt the terrorist.

Note: The above article appeared in Counterparts quarterly journal Sitrep in the Winter/Spring 2004 issue. Counterpart is an association of U.S.-Vietnamese advisors and their Vietnamese counterparts.

For more information on the author, the association and its periodical, contact: Ken Jacobsen; kjacobsen@knology.net

UPDATE 2008: TIME TO LEARN FROM VIETNAM AND JOHN PAUL VANN

PROBLEM #1. Snobby U.S. Military lusting for nation-state wars (NSWs) wrong for COIN/SASO operations: Consequences of American Narcissism in Iraq

"It was an accident to begin with. John Vann was my friend, I had known him in those three years I'd been in Vietnam and I'd see him periodically afterwards. When he was killed, I went to his funeral at Arlington in 1972, and it was like an extraordinary class reunion. Here were all the figures of Vietnam in this chapel. This man had left the army as a renegade lieutenant colonel, had gone back to Vietnam as a civilian, and ended the war holding a General's position even though he was a civilian. General Westmoreland was his chief pallbearer, and a few minutes before the ceremony started, Edward Kennedy, the last of the Kennedy brothers, came in. And I thought of the older brother who sent the country to fight this war in Vietnam in '62 when I first went there, already buried in this cemetery, and here was the youngest brother coming ... he was a friend of Vann's. Sitting with the family was Daniel Ellsberg, who was about to go on trial for copying the Pentagon Papers. He and Vann had remained best friends, despite going in totally opposite directions on the war. It was very moving. I realized that we were burying more than John Vann. We were burying the whole era of the war. We were burying the era of boundless self-confidence that led us to Vietnam. By that time, John had come to personify the war. He'd spent the better part of ten years there. Everyone else would go for a year or two, three at the most, and he'd spent the better part of ten. And I realized that if I wrote a book about him, I could write a history of the war. I could put the two together, and people might be able to understand the war because they would be reading about it in human terms, though the story of a man whose life turned out to be like a novel.

There was a moral outrage in what he was telling you about the war that you wound up conveying to the audience back home in the United States.

"Yes, there was a moral outrage on several levels. First of all, you've got to remember in that period of time, this country was at the high noon of its power. We thought that whatever we wanted to do was right and good, simply because we were Americans, and we would succeed at it because we were Americans. And Vann embodied that, and so did the reporters. We wanted to see this country win the war just as much as those advisors did. We felt we would help to do that by reporting the truth. And so there was the moral outrage over this General and the ambassador in Saigon who kept denying the truth we would see. I discovered later on that they believed these delusions. We thought they were lying to us; I discovered later on they believed what they were saying. They were really deluded men. And then there was the moral outrage over the way the war was being conducted. Vann had the keen sense of honor as a Soldier and he was enraged at the bombing and shelling of peasant hamlets, which was routinely done by the Vietnamese and American Generals. He thought, first of all, this was terrible. When I say keen sense of honor as a Soldier, he was in Vietnam to fight other men, not to kill somebody's mother or sister or kid. And he felt that, first of all, this was wrong, and secondly, it was stupid, because it was going to turn the population against us, and of course he was quite right. So a sense of moral outrage was conveyed on several levels, yes."

You quote him at one time as saying, "This is a political war, and it calls for the utmost discrimination in killing. The best weapon in killing is a knife." You emphasize his criticism of the indiscriminate bombing, which was really the way that we chose to pursue the war. The Generals were fighting another war, they were still fighting World War II, and it made no sense in the Vietnam context.

"When I got at the records, I realized that they also understood what they were doing. I mean, they thought that they could -- you know, Mao Zedong described guerrillas as fish swimming in the sea; well, they were going to empty the sea. And the Vietnamese Generals on the Saigon side thought that they could terrify their peasantry into ceasing to support the guerrillas. I think the American Generals, as it turned out later on, deliberately wanted to empty these areas of population".

JOHN PAUL VANN AS THE MODEL FOR TODAY'S U.S. ARMY LEADER

"The Mongols, a classic example of an ancient force that fought according to cyberwar principles, were organized more like a network than a hierarchy. More recently, a relatively minor military power that defeated a great modern power--the combined forces of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong--operated in many respects more like a network than an institution; it even extended political- support networks abroad. In both cases, the Mongols and the Vietnamese, their defeated opponents were large institutions whose forces were designed to fight set-piece attritional battles.

"Cyberwar is coming" by John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, International Policy Department

RAND

"Sheehan sees a Vietnam suffering not from the American war but from a prolonging of the agony by the rigid regime of Le Duan, with its prosecution of new wars and its Stalinist economics. In 1986, as General Giap relates in a longish and candid interview, came doi moi, or ``the new way.'' Out went the collective farms and heavy industrial projects; in came a free market. Within a year, Vietnam was exporting rice, and the currency had stabilized. Still, it's a desperately poor country, the North in particular, as Sheehan's tour of hospitals demonstrates: They are under-equipped and cannot afford to stock antibiotics or basic vaccines. In Saigon, Sheehan is overcome with memories and seeks out his and Susan's old haunts, as well as those of John Vann, subject of much of A Bright Shining Lie. Like the North, the South is a society run by party faithful--and the privileges of rank have hearkened to them, leaving out a great many of the ``mutilated.'' Even so, the armies of homeless have been eliminated, and no one is starving. In Saigon, Western influence is strongest, ready for the moment when the American embargo drops and Vietnam becomes the economic powerhouse everyone is anticipating. Already the BMWs proliferate."

Garrison Mentality in Iraq/Afghanistan: the "Presence Patrol" = Delegating COIN/SASO Dirty Work like it were lawn care

VIDEO PROOF: WHAT WRONG LOOKS LIKE: Trucks on Roads = Land Mines = Deaths

www.youtube.com/watch?v=txfHswsVJqg

www.youtube.com/watch?v=txfHswsVJqg

1. Stop "Presence patrolling": there is no PEACE to "keep"--so stop driving around aimlessly like a beat cop when being seen ENRAGES the populace as a foreign occupier; this isn't New York City where being seen deters crimes--it INVITES violence

2. STAY OFF ROADS: stop being so damn lazy.

Park ALL wheeled trucks since they cannot leave roads where land mines wait. WHY GIVE THE REBELS EASY TARGETS TO BLOW UP? If you have to go somewhere to set-up a checkpoint, guard an area, lay an ambush (security creating maneuvers) go in TRACKS and go by unpredictable, cross-country routes.

www.combatreform.org/armoredhmmwvsstrykersfail.htm

3. Don't Clusterfuck: no troops on foot in WW2 style formations in bad camouflage bunched together

www.combatreform.org/camie.htm

4. No Half-Assed Vehicle checkpoints: use BLAST WALLS to channelize incoming cars and compartmentalize any car bombs going off. Use a robot and/or bomb dog to inspect car for guns or explosives. No more than 1 man near the car and only if you have to; use loud speakers from a tracked armored vehicle and/or a guard tower covering the inspection proicess with rifle and machine gun fire and have person get out of car if IDed as a rebel and walk through a blast wall lane and have him swiped for guns/explosives--if he's wearing a bomb he only takes out some easily replaced blast walls

www.combatreform.org/highexplosives.htm

5. Stop accepting any war situations given; the responsibility of the general officer is to insist that the goals and means are moral and feasible

This video shows in alarming detail the incompetent "From Here to Eternity" U.S. Army and USMC suffering as victims due to its failure to know WHAT RIGHT LOOKS LIKE for a sub-national conflict.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=DnVZRgiOw-o

www.youtube.com/watch?v=DnVZRgiOw-o

The non-linear battlefield (NLB) is dominated by high explosives (HE); not feel-good, kinetic energy (KE) bullet gunslinger duels. Combat Engineering is the key. War is not a macho ego trip; its about whose WILL dominates the situation. A competent, professional Army SMOTHERS sub-national conflict violence and does not add to it. This can give time for a political settlement to be had, but we can ill afford to drag our feet on it...and if Iraq is just a corporation feeding frenzy backed by an illegitimate puppet government, then military men damn well better open their mouths to Congress and get a legitimate mission to accomplish by demanding real elections be held immediately--monitored by outside agencies to insure we just don't lie again and put another puppet in charge like Mr. Maliki.

BOTTOM LINE: Let's stop looking like and acting like a gadgetized version of the Red Coats.

Canadians in Afghanistan Fail in LAV3Stryker Trucks

www.youtube.com/watch?v=rm2cuwJati8

www.youtube.com/watch?v=rm2cuwJati8

PBS Documentary Afghanistan: The Other War, reveals that the emasculation of western armies into wheeled trucks like the LAV-III/Stryker to not LOOK war-like (ie; look less capable, which they are) cannot even overcome the battle against earth terrain to have basic mobility to reach people in closed terrains in jeopardy at the hands of sub-national groups rebelling against the nation-state. You look less capable means you ARE less capable and being weak with a "glass jaw" neither protects the good civilians nor engenders respect from the enemy. "Nation-building" in war zones in wheeled trucks is a disaster.

Also telling is the Canadian Multi-National Force Commander's obsession with self; who cares how history will judge him? The Mission and the Men should come before "Me". By being in road-bound wheeled trucks, the NATO MN forces have a "glass jaw" that makes it impossible to "turn- the-other-cheek" so they are trigger-happy trying to use firepower to compensate for a lack of M113 Gavin-type tracked cross-country mobility (avoid road troubles in first place) and armored protection. When NATO forces are caught red-handed needlessly killing Afghan civilians, as a Cover-Your-Ass (CYA) politician--maybe without a technotactical grasp of what his subordinates are doing--he gives the standard c'est la guerre (it is war, blame it not our incompetence or willful wrong-doing) excuses sure to infuriate the people whom we want to stay out of the Taliban's camp. He offers that the Soldiers might be court-martialed but he doesn't show any grasp that he has them in bad situations setting them up for such failures; for example they live in exposed tents when they should be in dug-in and Hesco-covered ISO shipping container "BATTLEBOXes" at their forward operating bases (FOBs).

WRONG

RIGHT

www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qdHqBKbaAI

www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qdHqBKbaAI

Hopefully, he and others will watch this PBS video and realize they need to hand out bright-orange traffic cones or saw horses so his troops can start actually visibly marking impromptu road blocks (place a sign on one of the cones/saw horses saying "STOP!" in the local language) at THE PROPER DISTANCE TO GIVE CAR BOMB STAND-OFF PROTECTION and stop the gleeful "warning shot" BS which lets cars/trucks get too close in the first place and results in needless dead/wounded innocent civilians.

WRONG

www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAJ46Wosrn0

www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAJ46Wosrn0

RIGHT

www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJpYvbu4KhU

www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJpYvbu4KhU

Do we want an excuse to open fire and kill "ragheads" confirming we are just there to take their oil/natural resources or do we want to do what's morally RIGHT and technotactically BEST to protect our troops and avoid misunderstandings that kill innocent civilians and feed the rebellion? For all the $$$ millions going into sexy helicopters to fly him around, surely he can afford some traffic cones/saw horses? Or some spark plugs? (see part 2). Watching the PBS video clipabove may not make these lessons obvious; maybe he and other decision-makers will read our captions here and follow the lead of the British and Dutch and re-equip ALL NATO forces with M113 Gavin or other type light tracks since Afghanistan's terrain is traversable by these low ground-pressure vehicles and not wheeled trucks with any armor protection. The Canadians to their credit, have since this video factored in their constant LAV3Stryker truck failures in Afghanistan and turned more and more to tracked vehicles.

Its clear that to do SASO/COIN operations properly, we need a dedicated non-linear, battlefield stability corps composed of older, more mature, psychologically-screened to not be narcissist "shooters" properly equipped with light M113 Gavin armored tracks, affordable 2-seat observation/attack, simple rotary and fixed-wing STOL aircraft to scour the skies 24/7/365 and not constantly crash like UAVs do and see hiding enemies with human eyesight plus sensory help---and plenty of combat engineers to repair the country's infrastructure and separation wall apart warring factions and security fence trouble-makers out.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=DsO54MQi6es

www.youtube.com/watch?v=DsO54MQi6es

PBS documentary shows a Canadian Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) at an isolated FOB in Afghanistan trying to win over a nearby village from Taliban rebel sympathy by repairing their water pumps and supplying other needed items. The kingdom is lost for want of a nail when the native contracted supply column is turned away because the bomb sniffing dog discovers a driver has traces of explosives. Why OPSEC is violated by having locals drive supplies to FOBs in the first place? Thus, they cannot get measly spark plugs and LAV-III/Stryker clusterfuck drive into a run-down road-side black market where their "shooter" foot narcissists hop out and proceed to "block" the road by NOT blocking it as if Afghans who have lived with guns for centuries are going to cower at them brandishing firearms.

"Look-At-Me-I-Have-A-Gun-Treat-Me-Like-god" Complex

When Afghans continue to drive because the Canadians didn't even post traffic cones or forward vehicles to stop traffic for convoys to pass, they eagerly open fire with "warning shots". Even when moving they don't feel safe in their allegedly "armored" LAV3Strykers spitting out warning shots left and right and causing a truck to over-turn and nearly killing an innocent Afghan. How many spark plugs would the UH-60 MEDEVAC helicopter flight have paid for if it had been prevented? How many brand-new water pumps?

A "pound-of-cure" MEDEVAC helicopter is flown in to fly him out, but the "ounce preventable" damage is already done. So much for "winning hearts and minds" this day. Emasculated ground troops in wheeled LAV-III/Stryker trucks are set up for road/trail restricted failure wherever they are.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZandbBaUw_U

www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZandbBaUw_U

Video begins with the PRT female officer explaining the need to win over the villagers to a smartass kill/capture enlisted narcissist obsessed with the "Taliban all around".

By conveniently being in wheeled LAV3/Strykers without cross-country mobility he is exempt from having to patrol or set up LP/OPs to scour the immediate area of his own FOB of Taliban asking for a M16 vs AK47 firefight.

What he can do when not sharpshooting his officers is play kill/capture on a laptop as his buddy nearby is doing. Me thinks he could better spend his time making some "STOP!" signs in the local Afghan language to bolster impromptu road blocks and prevent the need to "bust caps" into civilians. At 2: 58 yet another LAV3/Stryker clusterfuck convoy is sent down the road hit by a little rain to make contact with another village to win them over when they can't even keep their promises to their first village adjacent to their FOB. A LAV3Stryker gets stuck in a little mud ON THE ROAD and breaks its main bearing. While their officer spins a tail almost as fast as the rubber tires are in the deepening mud, the mission is ABORTED. The "recovery" LAV3Stryker yanks out the first truck but its hitched up to a regular LAV3Stryker to tow back to base. Then as the pair start to move--THEY BOTH GET STUCK in a minor mud rut that would be nothing for a light M113 Gavin armored track to drive through without even stopping to blink. With darkness falling, they need to get back to base before the Taliban come out; the NCOIC walks away in disgust he's been given crap wheeled vehicles to work with.

STILL PHOTOS OF THE LAV-III DEBACLE IN AFGHANISTAN (AMERICANS EXPERIENCE THIS DAILY, TOO)

2: "We are going to make contact with a new village and reach out to them and win over their hearts and minds in our low-maintenance, all-terrain, high-speed SASO wheeled vehicles. Our LAV-IIIs are used by the Americans who call them 'Strykers'".

3: "WAHOO! Look at Me! I'm going 60 miles per hour on the road!!" (Not for long!)

LAV-III stuck a 1st time; Road Speed: 0 MPH

4: "Ohhh....sh$%^&! I drove into a rut....."

5: "Can we get it out?"

6: "We had technical difficulties and had to cancel the mission to the village"

7: "What's that dangling underneath the LAV-III?"

8: "Oh No. Its the main bearing. Its broke, man. This thing won't run its trashed."

9: "What a Piece-of-Shit (POS)."

10: "Careful! Don't get the 'recovery' LAV-III stuck, too!"

11: "Oh Boy. The 'recovery' LAV-III is spinning in the mud, too."

12: "Please...please grip...grip....we don't want to be stuck here outside the wire when the sun goes down..."

LAV-III stuck a 2d time: and it gets another truck stuck, too!

13: "Gun it!!! Get through the dip!"

14: "Damn! We are Stuck Again! BOTH LAV3STRYKERS!!! Dude! It's Getting Dark!"

15: "We Got to get Back to the FOB before the Taliban come out!"

16: "Go Easy! Easy! Let the Wheels Catch!"

17: "Damn. Forget it. Cut the Engine!"

18: "Mission Aborted! Maybe an officer will figure this out."

"We REALLY showed our Afghan allies today why they should trust their very lives to us.

Yeah, Right. We need to turn these pieces-of-shit in and get tracks so we can win"

Fortunately, they survive the debacle and ask the nearby villagers to WALK TO THEM at the FOB to receive the supplies that finally arrive, compromising their own security as well as revealing the villagers to any watchful Taliban as being NATO sympathizers.

If this isn't bad enough, the smirking "shooters" tell them the doctor has run out of supplies and they must walk back to their village, essentially empty handed.

If these Canadians had M113 Gavins instead of LAV3Stryker wheels they could have DROVE the doctor cross-country to the village and done medical assistance and passed out whatever supplies they had---discreetly in a designated home.

Clearly, smirking nation-state war narcissists receiving full-time pay/benefits (welfare recipients in sexy uniforms) wrongly look down on these "ragheads" as "slackers" looking for a "free hand-out" when really they are Islamofascism victims who with a little help might be our friends-for-life if we respect their dignity and follow-through with our promises.

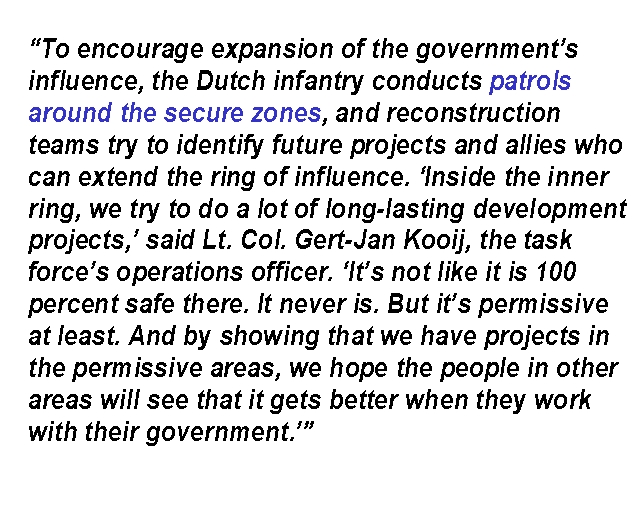

To CYA, the FOB is suddenly dismantled and removed from the area; violating the proven ink blot strategy of counter-insurgency which is to stay and expand goodwill--which is what the Dutch are succeeding at doing in Afghanistan using light mechanized M113 Gavins.

LAV-3/Strykerrrrs fail in Afghanistan and the Canadians ditch their own wheeled trucks they make for more mobile and better armored tracks!

Enter the Leopards and M113 MTVL Gavins!

www.youtube.com/watch?v=GrATZkFUhaI

www.youtube.com/watch?v=GrATZkFUhaI

The Dutch are using M113 Gavin tracks, too and are being VERY successful in counter-insurgency operations!

www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZKa3tK3zi4c

www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZKa3tK3zi4c

What caused the turn-around?

COMBAT.

REALITY.

AFGHANISTAN.

A DESIRE TO WIN, NOT CONTINUE TO LOSE IN WHEELED TRUCKS...

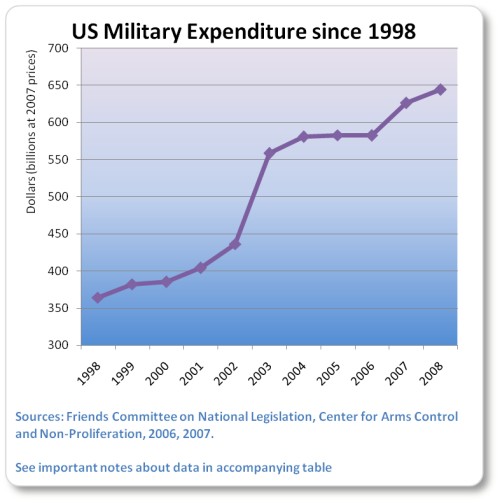

We need to stop wasting billions on fatally flawed, break-down-prone wheeled Stryker trucks that fail to get the job done and put our men into constant road/trail ambushes and put our money into M113 Gavin light for cross-country mobility but medium-weight in armor protection tracks that don't get stuck and break down in a mere light rain and minor mud.

Tom Ricks' article in the Washington Post reveals yet more reasons why we need a dedicated Non-Linear Battlefield or Sub-National Conflict Stability Corps (NLB-SC OR SNC-C) that would listen to all its Soldiers regardless of rank and not treat rebellions like it was just lawn care dirty work that lower ranks need to go out and prune. If what you are growing is "poison ivy" trimming it isn't the solution...the solution is to STOP GROWING WEEDS (making rebel humans). If we don't form a NLB-SC OR SNC-C we will have learned nothing from Iraq like we failed after Vietnam....and we will repeat all these mistakes again with more thousands of our young people paying for it with their lives and limbs! We need a NLB-SC OR SNC-C that is ready BEFORE the war to rapidly bring back TV, radio and telephone service and call out to former Army Soldiers and government employees to return to work the next day, and have THE MONEY TO PAY THEM to restore social order. We need to stop being so stingy. This also applies to Afghanistan (see article below Ricks' article). Garrison Army and marine generals who have everything provided to them, chow halls, direct deposit every 2 weeks etc. have no clue whatsoever of how civilian life is a struggle to make ends meet and that SOMEONE has to grow and prepare the food they take for granted as they walk intro a DFAC.... They all live in a phony, cloistered mini-society of "From Here to Eternity" garrison BS each day subsidized by U.S. tax payers to allegedly be "attack dogs" let out once every 10 years to do nation-state war, then returned to their garrison "cages". What we need to prevail in COIN/SASO is a helpful "Lassie" that can when threatened fend off attacks not kill/capture "Attack of the Dobermans" 24/7/365.

Living in Former dictator Palaces Enrages the Populace: DON'T DO IT!

www.youtube.com/watch?v=SmAhL8iPutA

www.youtube.com/watch?v=SmAhL8iPutA

The "presence patrol" mentality now ensconced in the new COIN manual FM 3-24 (LTG Petraeus is co-author with marine general Mattis) despite being a miserable failure in Iraq for over 4 years and Afghanistan for 5 years, is senior generals getting to live in comfortable palaces on FOBs as they delegate the dirty work of appeasing the masses to lower-ranking Soldiers who try to "cut deals" with them when the situation itself is already damned by the higher ranks' parameters. Its just the garrison mentality back in the states of the generals and colonels and majors ordering lower ranking personnel to mow lawns and polish floors, except this time its having Soldiers expose themselves to constant enemy ambush to placate the locals or to kill/capture the rebels to "tidy-the-area". Its not lower ranking "empowerment" its snobby delegating the "dirty work" to lower-ranking Soldiers to do EVERYTHING and somehow try to overcome SYSTEMIC problems CREATED BY THE SENIOR OFFICERS. For example, maybe the best CONOPS is to rehire the old Army and create town/village RF/PF security forces to keep rebels out, not have U.S. forces enter/leave villages/towns with "presence patrols" which exposes our men to road ambushes and yields control right back to the rebels? Real empowerment would not be a top-down, one-way RHIP tidy-my-area drill, it would be the lower-ranking Soldiers sitting at the table of the "councils of war" (Bible, God: "with wise counsel make war") and CHANGING THE SYSTEMIC PARAMETERS of the operation with their input so we have a WINNING CONOPS. "Presence patrolling" is senior officers trying to have junior Soldiers do their jobs without their power, funds and authority to change the conditions so they can at least have a chance to succeed.

Iraq: Kill/Capture/Torture: have U.S. troops tidy the area

www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/07/22/AR2006072201004.html

In Iraq, Military Forgot Lessons of Vietnam

Early Missteps by U.S. Left Troops Unprepared for Guerrilla Warfare

By Thomas E. Ricks

Washington Post Staff Writer

The real war in Iraq -- the one to determine the future of the country -- began on Aug. 7, 2003, when a car bomb exploded outside the Jordanian Embassy, killing 11 and wounding more than 50.

That bombing came almost exactly four months after the U.S. military thought it had prevailed in Iraq, and it launched the insurgency, the bloody and protracted struggle with guerrilla fighters that has tied the United States down to this day.

There is some evidence that Saddam Hussein's government knew it couldn't win a conventional war, and some captured documents indicate that it may have intended some sort of rear-guard campaign of subversion against occupation. The stockpiling of weapons, distribution of arms caches, the revolutionary roots of the Baathist Party, and the movement of money and people to Syria either before or during the war all indicate some planning for an insurgency.

But there is also strong evidence, based on a review of thousands of military documents and hundreds of interviews with military personnel, that the U.S. approach to pacifying Iraq in the months after the collapse of Hussein helped spur the insurgency and made it bigger and stronger than it might have been.

The very setup of the U.S. presence in Iraq undercut the mission. The chain of command was hazy, with no one individual in charge of the overall American effort in Iraq, a structure that led to frequent clashes between military and civilian officials.

On May 16, 2003, L. Paul Bremer III, the chief of the Coalition Provisional Authority, the U.S.-run occupation agency, had issued his first order, "De-Baathification of Iraq Society." The CIA station chief in Baghdad had argued vehemently against the radical move, contending: "By nightfall, you'll have driven 30,000 to 50,000 Baathists underground. And in six months, you'll really regret this."

He was proved correct, as Bremer's order, along with a second that dissolved the Iraqi military and national police, created a new class of disenfranchised, threatened leaders.

Exacerbating the effect of this decision were the U.S. Army's interactions with the civilian population. Based on its experience in Bosnia and Kosovo, the Army thought it could prevail through "presence" -- that is, Soldiers demonstrating to Iraqis that they are in the area, mainly by patrolling. "We've got that habit that carries over from the Balkans," one Army general said. Back then, patrols were conducted so frequently that some officers called the mission there "DAB"-ing, for "driving around Bosnia."

The U.S. military jargon for this was "boots-on-the-ground," or, more officially, the presence mission. There was no formal doctrinal basis for this in the Army manuals and training that prepare the military for its operations, but the notion crept into the vocabularies of senior officers. For example, a briefing by the 1st Armored Division's engineering brigade stated that one of its major missions would be "presence patrols." And then-Maj. Gen. Ricardo S. Sanchez, then the commander of that division, ordered one of his brigade commanders to "flood your zone, get out there, and figure it out." Sitting in a dusty command tent outside a palace in the Green Zone in May 2003, he added: "Your business is to ensure that the presence of the American Soldier is felt, and it's not just Americans zipping by." [EDITOR: he wouldn't be in that tent for long with a posh palace nearby]

The flaw in this approach, Lt. Col. Christopher Holshek, a civil affairs officer, later noted, was that after Iraqi public opinion began to turn against the Americans and see them as occupiers, "then the presence of troops . . . becomes counterproductive."

The U.S. mission in Iraq is made up overwhelmingly of regular combat units, rather than smaller, lower-profile Special Forces units. And in 2003, most conventional commanders did what they knew how to do: send out large numbers of troops and vehicles on conventional combat missions.

Few U.S. Soldiers seemed to understand the centrality of Iraqi pride and the humiliation Iraqi men felt in being overseen by this Western army. Foot patrols in Baghdad were greeted during this time with solemn waves from old men and cheers from children, but with baleful stares from many young Iraqi men.

Complicating the U.S. effort was the difficulty top officials had in recognizing what was going on in Iraq. Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld at first was dismissive of the looting that followed the U.S. arrival and then for months refused to recognize that an insurgency was breaking out there. A reporter pressed him one day that summer: Aren't you facing a guerrilla war?

"I guess the reason I don't use the phrase 'guerrilla war' is because there isn't one," Rumsfeld responded.

A few weeks later, Army Gen. John P. Abizaid succeeded Gen. Tommy R. Franks as the top U.S. military commander in the Middle East. He used his first news conference as commander to clear up the strategic confusion about what was happening in Iraq. Opponents of the U.S. presence were conducting "a classical guerrilla-style campaign," he said. "It's a war, however you describe it."

That fall, U.S. tactics became more aggressive. [EDITOR: kill/capture] This was natural, even reasonable, coming in response to the increased attacks on U.S. forces and a series of suicide bombings. But it also appears to have undercut the U.S. government's long-term strategy.

"When you're facing a counterinsurgency war, if you get the strategy right, you can get the tactics wrong, and eventually you'll get the tactics right," said retired Army Col. Robert Killebrew, a veteran of Special Forces in the Vietnam War. "If you get the strategy wrong and the tactics right at the start, you can refine the tactics forever, but you still lose the war. That's basically what we did in Vietnam."

For the first 20 months or more of the American occupation in Iraq, it was what the U.S. military would do there as well. "What you are seeing here is an unconventional war fought conventionally," a Special Forces lieutenant colonel remarked gloomily one day in Baghdad as the violence intensified. The tactics that the regular troops used, he added, sometimes subverted American goals.

Draconian Interrogation Ideas

On the morning of Aug. 14, 2003, Capt. William Ponce, an officer in the "Human Intelligence Effects Coordination Cell" at the top U.S. military headquarters in Iraq, sent a memo to subordinate commands asking what interrogation techniques they would like to use.

"The gloves are coming off regarding these detainees," he told them. His e-mail, and the responses it provoked from members of the Army intelligence community across Iraq, are illustrative of the mind-set of the U.S. military during this period.

"Casualties are mounting and we need to start gathering info to help protect our fellow Soldiers from any further attacks," Ponce wrote. He told them, "Provide interrogation techniques 'wish list' by 17 AUG 03." [EDITOR: instead of stopping the BS presence patrolling in Humvee trucks/on foot with tracked Security Creating Maneuvers, let's kill/capture/torture and try to attrit the bad guys with RMA air strike rather than change ourselves to do maneuver better]

Some of the responses to his solicitation were enthusiastic. With clinical precision, a Soldier attached to the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment recommended by e-mail 14 hours later that interrogators use "open-handed facial slaps from a distance of no more than about two feet and back-handed blows to the midsection from a distance of about 18 inches." He also reported that "fear of dogs and snakes appear to work nicely." The 4th Infantry Division's intelligence operation responded three days later with suggestions that captives be hit with closed fists and also subjected to "low-voltage electrocution."

But not everyone was as sanguine as those two units. "We need to take a deep breath and remember who we are," cautioned a major with the 501st Military Intelligence Battalion, which supported the operations of the 1st Armored Division in Iraq. "It comes down to standards of right and wrong -- something we cannot just put aside when we find it inconvenient, any more than we can declare that we will 'take no prisoners' and therefore shoot those who surrender to us simply because we find prisoners inconvenient." Feeding the interrogation system was a major push by U.S. commanders to round up Iraqis. The key to "actionable intelligence" was seen by many as conducting huge sweeps to detain and question Iraqis. Sometimes units acted on tips, but sometimes they just detained all able-bodied males of combat age in areas known to be anti-American. [EDITOR: creating rebels for sure]

These steps were seen inside the Army as a major success story, and they were portrayed as such to journalists. The problem was that the U.S. military, having assumed it would be operating in a relatively benign environment, wasn't set up for a massive effort that called on it to apprehend, detain and interrogate Iraqis, to analyze the information gleaned, and then to act on it.

"As commanders at all levels sought operational intelligence, it became apparent that the intelligence structure was undermanned, under-equipped and inappropriately organized for counter-insurgency operations," Lt. Gen. Anthony R. Jones wrote in an official Army report a year later. Senior U.S. intelligence officers in Iraq later estimated that about 85 percent of the tens of thousands rounded up were of no intelligence value. [EDITOR: they are now rebels for sure] But as they were delivered to the Abu Ghraib prison, they overwhelmed the system and often waited for weeks to be interrogated, during which time they could be recruited by hard-core insurgents, who weren't isolated from the general prison population.

In improvising a response to the insurgency, the U.S. forces worked hard and had some successes. Yet they frequently were led poorly by commanders unprepared for their mission by an institution that took away from the Vietnam War only the lesson that it shouldn't get involved in messy counterinsurgencies. The advice of those who had studied the American experience there was ignored. [EDITOR: who has time to sudy COIN/SASO? We got lawns to mow, change-of-command ceremonies to attend etc.]

That summer, retired marine Col. Gary Anderson, an "expert" in small wars, was sent to Baghdad by the Pentagon to advise on how to better put down the emerging insurgency. He met with Bremer in early July. "Mr. Ambassador, here are some programs that worked in Vietnam," Anderson said. It was the wrong word to put in front of Bremer. "Vietnam?" Bremer exploded, according to Anderson. "Vietnam! I don't want to talk about Vietnam. This is not Vietnam. This is Iraq!". [EDITOR: Bremer should have been fired immediately after issuing his De-Baath and fire Iraqi Army orders, and these ordered counter-manded]

This was one of the early indications that U.S. officials would obstinately refuse to learn from the past as they sought to run Iraq. One of the essential texts on counterinsurgency was written in 1964 by David Galula, a lieutenant colonel in the French army who was born in Tunisia, witnessed guerrilla warfare on three continents and died in 1967. When the United States went into Iraq, his book, "Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice," was almost unknown within the military, which is one reason it is possible to open Galula's text almost at random and find principles of counterinsurgency that the American effort failed to heed. Galula warned specifically against the kind of large-scale conventional operations the United States repeatedly launched with brigades and battalions, even if they held out the allure of short-term gains in intelligence. He insisted that firepower must be viewed very differently than in regular war.

"A Soldier fired upon in conventional war who does not fire back with every available weapon would be guilty of a dereliction of his duty," he wrote, adding that "the reverse would be the case in counterinsurgency warfare, where the rule is to apply the minimum of fire."

The U.S. military took a different approach in Iraq. It wasn't indiscriminate in its use of firepower, but it tended to look upon it as good, especially during the big counteroffensive in the fall of 2003, and in the two battles in Fallujah the following year.

One reason for that different approach was the muddled strategy of U.S. commanders in Iraq. As civil affairs officers found to their dismay, Army leaders tended to see the Iraqi people as the playing field on which a contest was played against insurgents. In Galula's view, the people are the prize. [EDITOR: why we need a NLB-SC OR SNC-C to be Civil Affairs Command's body guards/muscle so the dumb-ass nation-state war kill/capture/torture types don't run the show into the ground]

"The population . . . becomes the objective for the counterinsurgent as it was for his enemy," he wrote.

[EDITOR: Oh really? According to FM 3-24, MILITARY CONTROL is the number #1 priority, the support of the populace is secondary].

From that observation flows an entirely different way of dealing with civilians in the midst of a guerrilla war. "Since antagonizing the population will not help, it is imperative that hardships for it and rash actions on the part of the forces be kept to a minimum," Galula wrote. Cumulatively, the American ignorance of long-held precepts of counterinsurgency warfare impeded the U.S. military during 2003 and part of 2004. Combined with a personnel policy that pulled out all the seasoned forces early in 2004 and replaced them with green troops, it isn't surprising that the U.S. effort often resembled that of Sisyphus, the king in Greek legend who was condemned to perpetually roll a boulder up a hill, only to have it roll back down as he neared the top.

Again and again, in 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2006, U.S. forces launched major new operations to assert and reassert control in Fallujah, in Ramadi, in Samarra, in Mosul.

"Scholars are virtually unanimous in their judgment that conventional forces often lose unconventional wars because they lack a conceptual understanding of the war they are fighting," Lt. Col. Matthew Moten, chief of military history at West Point, would comment in 2004.

When Maj. Gregory Peterson studied a few months later at Fort Leavenworth's School of Advanced Military Studies, an elite course that trains military planners and strategists, he found the U.S. experience in Iraq in 2003-2004 remarkably similar to the French war in Algeria in the 1950s. Both involved Western powers exercising sovereignty in Arab states, both powers were opposed by insurgencies contesting that sovereignty, and both wars were controversial back home.

Most significant for Peterson's analysis, he found both the French and U.S. militaries woefully unprepared for the task at hand. "Currently, the U.S. military does not have a viable counterinsurgency doctrine, understood by all Soldiers, or taught at service schools," he concluded.

Casey Implements a New Tactic

In mid-2004, Gen. George W. Casey Jr. took over from Sanchez as the top U.S. commander in Iraq. One of Casey's advisers, Kalev Sepp, pointedly noted in a study that fall that the U.S. effort in Iraq was violating many of the major principles of counterinsurgency, such as putting an emphasis on killing insurgents instead of engaging the population.

A year later, frustrated by the inability of the Army to change its approach to training for Iraq, Casey established his own academy in Taji, Iraq, to teach counterinsurgency to U.S. officers as they arrived in the country. He made attending its course there a prerequisite to commanding a unit in Iraq. "We are finally getting around to doing the right things," Army Reserve Lt. Col. Joe Rice observed one day in Iraq early in 2006. "But is it too little, too late?"

One of the few commanders who were successful in Iraq in that first year of the occupation, Lt. Gen. David Petraeus, made studying counterinsurgency a requirement at the Army's Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, where mid-career officers are trained.

By the academic year that ended last month, 31 of 78 student monographs at the School of Advanced Military Studies next door were devoted to counterinsurgency or stability operations, compared with only a couple two years earlier.

And Galula's handy little book, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, was a best-seller at the Leavenworth bookstore.

Here are the Kill/Capture/torture "weeds" the garrison generals want "pulled" as if once these folks are annihilated, there will be no rebellion.

Occupation Racket: Corporations Get $$RICH$$$; Soldiers Get Dead, Maimed and Ruined for Life

Having 158, 000 American troops--troops in trucks and "boots" on the ground is NOT the best way to handle a SASO/COIN operation--LESS men say 50, 000 in well-armored TRACKS backed by separation walls and border fences--combat engineering means--otherwise we will ruin 1/3 of all the Soldiers for life and bankrupt the nation.

The Joseph Stiglitz Report

Nobel Prize Winner in Economics Harvard University

Stiglitz report says 1/3 of our troops whenever they deploy overseas to a combat zone will be scarred for life and every 100, 000 of these equals $1 BILLION of annual VA medical care costs for the rest of their lives.

353, 000+ out of 1.6M deployed = $3.5 BILLION per year from now until at least another 40 years. If these 20-year olds live to 60ish the costs of the Iraq debacle to make corporations rich will be the current $2 BILLION/week until we leave plus $140 BILLION in VA care by 2048.

http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20080505/ts_alt_afp/healthuspsychiatryiraqafghanistan

Soldier suicides could trump war tolls: U.S. health official

Mon May 5, 2008

1:11 PM ET

WASHINGTON (AFP) - Suicides and "psychological mortality" among U.S. Soldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan could exceed battlefield deaths if their mental scars are left untreated, the head of the US Institute of Mental Health warned Monday.

Of the 1.6 million U.S. Soldiers who have been deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan, 18-20 percent -- or around 300,000 -- show symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression or both, said Thomas Insel, head of the National Institute of Mental Health.

An estimated 70 percent of those at-risk Soldiers do not seek help from the Department of Defense or the Veterans Administration, he told a news conference launching the American Psychiatric Association's 161st annual meeting here.

If "one just does the math", then allowing PTSD or depression to go untreated in such numbers could result in "suicides and psychological mortality trumping combat deaths" in Iraq and Afghanistan, Insel warned.

More than 4,000 U.S. Soldiers have died in Iraq since the U.S. invasion of 2003, and more than 400 in Afghanistan since the U.S. led attacks there in 2001, of which some 290 were killed in action and the rest in on-combat deaths.

"It's predicted that most Soldiers -- 70 percent -- will not seek treatment through the DoD or VA," Insel said at the meeting, at which the psychological impact of war is expected to top the agenda over the next four days.

Left untreated, PTSD and depression can lead to substance abuse, alcoholism or other life-threatening behaviors.

"It's a gathering storm for the civilian and public health care sectors," Insel said.

He urged public-sector mental health caregivers to recognize the symptoms of psychological troubles resulting from deployment to a war zone and be ready to provide adequate care for both Soldiers and their families.

Other items on the agenda at the meeting, set to be attended by some 19,000 psychiatrists and mental health practitioners from around the world, include violence in schools, the psychology of extremism, and more light-hearted topics such as how music affects mood.

Below offers a list of major known Sunni insurgent/terror groups identified in Iraq and some very top level info about them. For some absurd reason It ignores the Shi'ite militias, the al-Qaeda "foreign fighters" cells, and the Iranian and Saudi agents supporting "their side." The listing was drawn from (other) websites by the folks at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the publishers of Foreign Policy magazine and long-time apologists for the UN and its internationalist, one-worlder agenda.

www.foreignpolicy.com/resources/alert.php

Foreign Policy, Posted June 19, 2006Before the U.S. military killed Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of al Qaeda in Iraq was the face of the insurgency. Yet his group was probably responsible for only 5-10 percent of the insurgent attacks. What about the other 90 percent? FP takes a look at the other major [Sunni] insurgent groups in Iraq--who they are, what they are trying to accomplish, and which ones are more likely to negotiate than fight to the death.

1. Ansar Al Islam

courtesy IslamOnline www.islamonline.net/english/In_Depth/Iraq_Aftermath/2003/12/ article_05.shtml

First surfaced: In December 2001, before the war.

Ideology: Ansar Al Islam is a violent group of extreme Islamist fundamentalists, not unlike the Taliban in Afghanistan. With close ties to al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, the group fervently opposes the U.S. presence in Iraq. More specifically, it rejects the U.S.-backed Patriotic Union of Kurdistan Party, which favors Kurdish self-determination and is led by the prominent Iraqi politician Jalal Talabani.