Those who Put Planes in the Air From the Sea Win: Those who Don't, Lose

By Mike Sparks

One of my gripes with the 1965 movie "Thunderball" and the 1983 remake "Never Say Never Again" is that they are not faithful to Commander Ian Fleming's book which has fixed-wing SEAPLANES figure prominently in the story. Evil villain Largo operates a seaplane from his high-speed yacht, the Disco Volante which he uses to move the nuclear bombs he captured from a British bomber flown by a traitor who earlier in WW2 had stolen a Fw-200 Condor maritime patrol bomber to England.

When CIA agent Felix Leiter and James Bond go looking for where the British bomber was ditched into the sea, they fly a SEAPLANE to get the long-range endurance and necessary ability-to-land-on-the-water-to-investigate capabilities. In the first screen adaptation of the Fleming novel, Leiter and Bond fly a short-range helicopter with floats that frankly is unlikely to have even offered enough flight time to find a bomber even resting in shallow water.

At least later on in the 007 movie series, Roger Moore playing Bond flies a Republic SeaBee amphibian in a daring low-level penetration to Scaramanga's island fortress in The Man with the Golden Gun to showcase seaplanes as Fleming intended.

WHAT RIGHT LOOKED LIKE: Long-Range Seaplanes that Could Patrol

What's worse is that life is even more emasculated than art: the U.S. Navy has abandoned long-range seaplanes in favor of short-range helicopters--placing their entire survival in a modern war in question.

WHAT WRONG LOOKS LIKE TODAY: Short-Range Helicopters Cannot Patrol

As THE leading naval intelligence expert in WW2, Fleming knew the value of seaplanes provided by their fixed-wing efficiency and speeds rotary-wing aircraft cannot match since during the war we were stung many times by the actions of enemies in seaplanes. Our laziness with helicopters threatens us into a repeat of WW2 mistakes when we didn't put planes into the air from the sea.

www.combatreform.org/seaplanefighters.htm

Fleming was also directly involved in breaking the German codes via the "Ultra Secret" and to protect it from the Germans realizing it, we had to be able to send planes in quickly to "find" Axis ships to create a cover story like during the Battle of Matapan:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cape_Matapan

The interception was made possible by

The Italian Fleet was spotted by a

War in the Atlantic: British Seaplanes Win--Beware of the Lessons of the Graf Spee

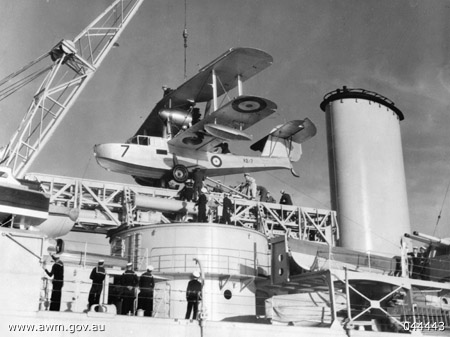

Manned Royal Navy seaplane launches from her ship to direct naval gunfire against German and/or Italian targets

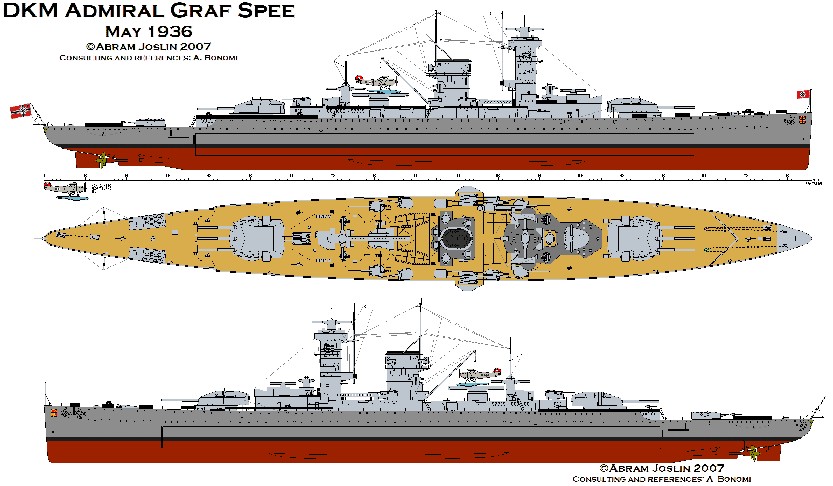

The concept of a pocket battleship--a cruiser's speed and range but with heavy armament and armor to be able to ward off enemy cruiser attacks while sinking civilian cargo ships during independent actions is a good one IF it has "hip-pocket" air cover in the form of seaplane fighters. We believe bringing our Iowa class battleships back to active duty with F-35B Lightning II stealthy STOVL fighter-bombers can achieve this. Moreover, if the Iowas were fitted with nuclear propulsion means, their fuel tanks could be used to store more JP-8 aviation fuel and they could sail at high speeds despite having a fat hull shape all over the world like a slim hulled cruiser--but without having to refuel except once every 10 years. Only the Iowas have the required armor to withstand precision guided munitions (PGM) attacks in the current era of flimsy ships fatalistically surrendered to the notion that everyone is going to be hit and there's nothing that can be done about it--except to hit first.

combatreform.org/battleships.htm

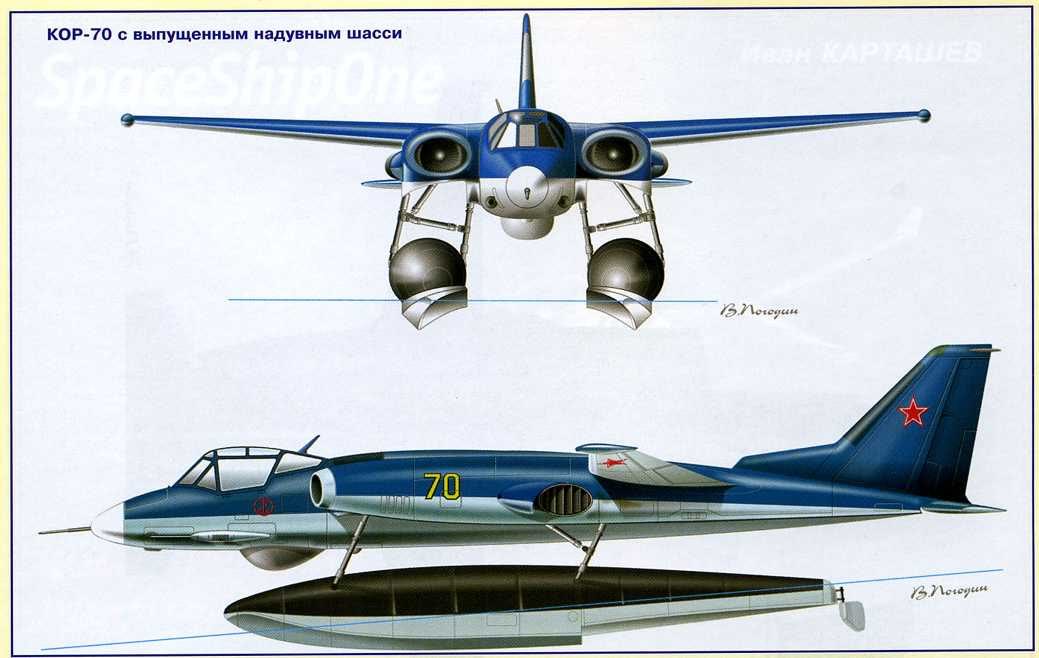

What is extremely fascinating in the account of the Graf Spee is the awareness on the part of both the German and British navies of the need to BREAK CONTACT in a surface action if not a part of a powerful surface fleet. As great as the Graf Spee was she had the fatal flaws of still being 7 knots (9 mph) slower than a Royal Navy cruiser and her AR-196 seaplane fighter was carried exposed and could be easily destroyed in combat if enemy fire were received---of course she should be up in the air before this happens to direct gunfire or attack or defend but this is not always possible. A nuclear-powered Iowa aircraft battleship would have raw power and have the combat seaplane fighters to not allow enemy ships to shadow her out of range as the Exeter, Ajax and Achilles did to the Graf Spee. The fascinating problem of independent actions is how to break contact on the surface; submarines can hide by being under the water. The clever German captain Langsdorff--a veteran from the WW1 battle of Jutland--had the Graff Spee fly British or French flags, call-in their name as other German warships and even built fake turrets and engine stacks from wood/canvas to appear like a RN battleship. A couple years later, the RN would trick the Germans by making the HMS Campbletown look like one of their destroyers by REMOVING engine stacks and reshaping her bridge for the St. Nazaire Raid! Flying false flags was SOP for the German armed civilian cargo ships.

www.bobhenneman.info/bhrcgs.htm

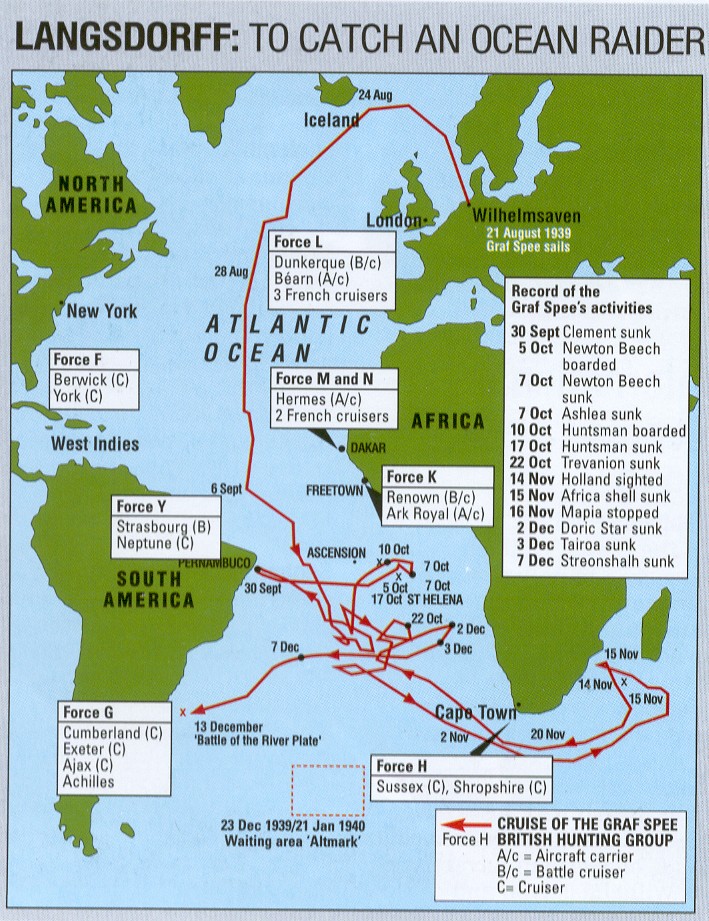

The Raiding Cruise of the Admiral Graf Spee

With the invasion of Poland pending, as war imminent, Germany dispatched her two available panzerschiffe into the Atlantic. Supply ships and tankers were dispatched also, to keep the warships at sea in the absence of German bases.

Admiral Graf Spee, under the command of Captain Langsdorff, slipped out of Wilhelmshaven on August 21, 1939, and sailed up the coast of Norway. The ship then turned west, passing unseen between the Faeroes Islands and Iceland on August 24. Graf Spee headed south, passing through the main Atlantic shipping lanes at night, to take up station northeast of the Azores. Here, on the 28th, Graf Spee met up with the supply ship Altmark, which, in the guise of an ordinary merchant tanker, had filled her holds in Texas with fuel oil for the raider. After topping of Graf Spee's bunkers, Altmark fell in behind the warship as they headed further south.

On September 3, 1939, British and France declared war on Germany over the invasion of Poland. Graf Spee and Altmark were west of the Cape Verde Islands, still heading south.

Despite the outbreak of hostilities, the raider was not allowed to commence warfare against Allied shipping, but was rather ordered on September 5 to avoid all contact with other ships. In the vain hope that a quick German victory in Poland and a lack of hostile action against British and French forces would lead to a very quick end to the war. So Langsdorff kept clear of shipping routes, crossing the equator on September 8 and taking up station in a seldom-frequented area of the South Atlantic.

The twin float design causes a seaplane to land very hard on the water; a single float cuts through waves better; the hard landing properties of the AR-196 resulted in water splashing into its air-cooled engine cracking the cylinder heads. A fortunate design flaw for the Allies.

On September 11, Graf Spee's Arado seaplane, on a routine recognizance flight, spotted the British heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland on an intercept course with the German ships. The British lookouts did not spot the plane, which was able to alert Langsdorff to change course and avoid detection. Cumberland continued on her way from Freetown to Rio de Janeiro, none the wiser. Graf Spee remained in a holding pattern north of the River Platte - Cape of Good Hope shipping route, refueling twice from Altmark.

On September 26, Langsdorff finally received new orders. Her was to commence hostilities immediately, but with several restrictions: he was to attack only British ships, and not French ships. Actions with enemy warships were to be avoided, so as to not risk his ship. He was also to conduct warfare within the rules of the International Prize Law, in that all ships needed to be stopped and searched, and their crews and passengers taken off before it could be fired upon. Lastly, he was to avoid any incident that would alienate U.S. opinion. Parting company with Altmark, Graf Spee went off to war.

As a lone unit in a hostile sea, Graf Spee would rely on cunning and confusion to avoid being cornered by enemy warships. She would display British and French flags to approach unsuspecting victims, and would change the name painted on her hull and her report signal ID several times, from Graf Spee to Deutschland to Admiral Scheer and back, so that any intercepted signals or reports of her sighting would cause confusion at the British Admiralty and lack credibility: a report from a neutral freighter of a "confirmed sighting" of a ship know to be in the Baltic would be looked upon skeptically.

Not being required to respect the U.S.'s self-declared "neutrality zone," Langsdorff headed towards the coast of Brazil, to disrupt the flow of meat and grain to Britain along the shipping routes off Pernambuco. 75 miles northeast of the Brazilian port of Pernambuco, Graf Spee found her first victim just before noon on September 30. The captain of the 5050-ton freighter SS Clement spotted an approaching warship, and thought it was the British cruiser HMS Ajax. But it was Graf Spee, who's Arado 196 seaplane was launched, and few machine gun bullets were sprayed at the bridge of the freighter. Clement's captain, F.C.P. Harris, stopped engines immediately, and ordered his crew to the boats after sending a distress message. Five rounds of 11" and 25 rounds of 5.9" gunfire then sank the abandoned freighter. The sea was calm, so Langsdorff took captain Harris, his chief engineer, and a hand injured while abandoning ship on board the Graf Spee, while the rest of the crew were given the correct course back to the South American port of Maceio, all reaching that location safely the next day. After treating the wounded man and questioning Harris, Langsdorff stopped the Greek steamer SS Papelemos. Her captain promised not to send a signal until reaching the Cape Verde Islands (a promise he kept), so the three British men were transferred to the neutral freighter and Graf Spee went on her way.

Knowing that Clement had gotten off a radio signal, Langsdorff took the Graf Spee off at high speed, choosing the Cape of Good Hope - Europe route as his next hunting ground. In that shipping route on October 5 Graf Spee found the British freighter SS Newton Beach (4650-tons) with a cargo of corn. The ship was stopped and a prize crew put on board so she could be used as a source of supplies, but not before a distress message was transmitted. Another British merchant ship heard this call, and passed it on later in the day to the HMS Cumberland. This was the worst case scenario for the Germans: a powerful British warship was in the area, the location of the raider was known, and heavy Allied reinforcements could be rapidly dispatched from Dakar, the West Indies, and Pernambuco to track down the raider within a few days. But Captain Fallowfield of the Cumberland, concerned with tipping off the position of his own vessel, incorrectly assumed that the radio call had been heard at Freetown, so he maintained radio silence. Graf Spee's luck had held out again.

Heading east in the company of her prize, Graf Spee surprised the British steamer Ashlea (4220-tons) on October 7, which was loaded with sugar. Her radio operator had no chance to send a message, and the ship was boarded. The Germans gained useful intelligence when her captain, C. Pottinger, failed to destroy his confidential instructions from the Admiralty. Clement's captain had made the same mistake, and the German raider was now in possession, among other valuable documents, of a complete copy of the code given by the Admiralty to merchant ships. Langsdorff now had Ashlea's crew was put onto Newton Beach, and Ashlea was sunk with scuttling charges.

On October 8, German High Command dispatched the battlecruiser Gneisenau, the light cruiser Koln, and nine destroyers into the North Sea. They were to simulate a sortie into the Atlantic, going only as far as the south coast of Norway, attacking any light craft or merchant ships they encountered. After being sighted by Coastal Command, they would slip back to Germany. This had the effect of the Home Fleet being put to sea immediately, and the Admiralty, fearful of a German breakout into the Atlantic, was dissuaded from sending heavy units to join the hunt for Graf Spee.

On October 9, aircraft from the [aircraft carrier] Ark Royal sighted Altmark southwest of the Cape Verde Islands. Captain Dau of the Altmark indicated that he was the American ship Delmar, and unwilling to take his flagship too far off its course for Freetown, Vice-Admiral Wells chose not to investigate, and the German supply ship was allowed to go on her way without even a cursory check. Altmark met with Graf Spee later that day, and received the transferred the crews of the two British ships. Having gotten all he wanted off Newton Beach, Langsdorff ordered her scuttled.

On the evening of the 10th, Graf Spee approached the British liner Huntsman (8200-tons), on passage from Calcutta to London with a cargo of tea. The liner's captain, A.H. Brown, mistook Graf Spee for a British cruiser, and allowed her to approach. The Germans then sent a signal threatening to open fire if the radio were used. Unwilling to risk the lives of his crew, Brown complied, and a prize crew took over Huntsman.

Returning to the waiting area outside the sea-lanes, Graf Spee refueled from Altmark. Though the Huntsman would make a good addition to the German war effort, Langsdorff realized that the chances of sailing her to Germany past the Royal Navy blockade were slim. Her captain joined the Graf Spee, while the rest of her crew was put on Altmark, and the ship was scuttled.

Using intercepted radio transmissions and his captured codebook, Langsdorff headed south for another try at the Cape - UK trade route. On October 22 Graf Spee, flying a French flag, approached within a mile of the 5300-ton Trevenion. Her captain, J. Edwards, recognized the pocket battleship and sent off a distress call at the last minute, completing it despite machine gun fire to the bridge of his ship. The Germans boarded the vessel, took off the crew, and scuttled her, but a British liner relayed her message to the C-in-C at Freetown. Realizing that his game was up, Langsdorff left the shipping lanes once again. He rendezvoused with Altmark on October 29 to refuel and transfer all of his prisoners. Admiral Raeder in Berlin suggested new hunting grounds, and Langsdorff agreed: the Indian Ocean. It was time for the wool harvest in Australia, and the Cape of Good Hope - Australia trade route should be both filled with valuable prizes and poorly defended.

Heading southeast, Graf Spee sailed for over 3000 miles, staying far south of the cape of Good Hope, which the raider passed on November 3. A message from Berlin commended the Graf Spee for her efforts and 100 Iron Crosses were awarded to her crew.

But the Cape - Australia trade route in the Indian Ocean did not bring the prey the Germans anticipated. The wool clipping in Australia came late that year, and the ships carrying it were sitting in Australia, not yet loaded. For 10 frustrating days Graf Spee slowly cruised in search of ships, sighting none.

So Langsdorff headed to the Mozambique Channel, between the African coast and Madagascar. On November 15 Graf Spee took the tiny British tanker Africa Star (700-tons) by surprise, capturing her before a distress call could be sent. The captain, P. Dove, and his crew were taken on board Graf Spee and the diminutive tanker, loaded only with ballast, was scuttled.

The next day Graf Spee closed on another vessel, only to find that it was the neutral SS Mapia, of Dutch registry. Her neutrality was respected and she was allowed to go, but Langsdorff decided that between her inevitable report upon reaching port, and the Africa Star being eventually reported late, he had just about worn out his welcome in the Indian Ocean. He sailed back to the Atlantic, passing the Cape on November 21.

Two days later Graf Spee arrived back at her original South Atlantic waiting area, where four days were spend in company with Altmark making repairs and adjustments to Graf Spee's engines. To confuse any ships that may have stumbled upon him in such a vulnerable state, Langsdorff ordered a second forward turret and second funnel constructed out of wood and canvas, radically altering the silhouette of his vessel to resemble HMS Renown. To pull British warships away from the area, the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau put to sea for a feint into the North Atlantic, disrupting Allied shipping and trying up the Home Fleet for a week before returning unseen to Germany.

Langsdorff decided that his ship and crew were about ready to go home. Having sailed over 30,000 miles, Graf Spee's engines were in need of more repairs than could be made at sea. Langsdorff decided to make one more sweep of South America to disrupt trade along the coast to the UK, and then head back to Germany for a well-deserved overhaul for his ship and R&R for his crew. He would first hunt the Cape-UK trade route until December 6, and once the enemy was aware of his presence he would take his ship to the River Plate area for a final sweep against beef and wheat from Argentina, and head for Germany with the New Year. Refueling and provisioning from Altmark on November 26, Langsdorff decided to redistribute his prisoners. Captains and first officers would return to Germany on Graf Spee, while Altmark would land the rest at a neutral port. Ironically, Langsdorff wrote that because Graf Spee's period of commerce raiding was nearing the end, it was no longer absolutely necessary to avoid action with enemy warships. Should an enemy warship sight and attempt to follow Graf Spee, he would close the range and use his ship's powerful guns to at least damage it so as to eliminate the threat of a shadowing warship calling in reinforcements.

The two ships separated, and Graf Spee made her presence known off Africa on December 2. The liner Doric Star (10,100-tons) was sighted bound for Britain from New Zealand with mutton, butter, cheese, and wool. Rather than use disguise, Langsdorff opened fire from long range, which allowed the liner to send a distress call before being overwhelmed. This properly stirred up a hornet's nest in the area, and the Germans planned to put a prize crew on the liner for later use as a supply ship before dashing across the Atlantic. But just as German seamen boarded this valuable prize with her rich cargo, Graf Spee's seaplane ran out of fuel and had to make a forced landing. Recalling his crew, he ordered the liner scuttled, and raced off to recover his valuable aircraft and its crew, which were located just before nightfall.

At sunrise on the 3d, Graf Spee captured the steamer Tairoa (7980-tons), sinking her after taking off the crew. But Tairoa's captain Star had gotten off a distress signal before is radio room was wrecked by gunfire.

On December 6, Graf Spee met up with Altmark again. After exchanging prisoners for fuel and provisions, Graf Spee headed westward to the River Plate area. Captains Star and Brown (Huntsman) were also transferred to Altmark, so that they might look after the captive crewmen.

On the evening of December 7, Graf Spee sighted the freighter SS Streonhalh (4000-tons) bound for Britain from Montevideo. Her captain, J. Robinson, hoped that Graf Spee was a British cruiser and delayed sending a distress call until it was too late. Robinson attempted to dispose of his secret documents in weighted bags, but a German sailor saved one before it sank. From this packet Langsdorff learned that British shipping leaving Buenos Areas and Montevideo steered for a point 300 miles east of the River Plate, before turning north-northeast past Pernambuco for Freetown. Langsdorff now knew where to find rich pickings before heading back to Germany. After taking off the crew, the ship was scuttled, bringing Graf Spee's total to nine vessels totaling more than 50,000 tons, without a sailor on either side being killed or wounded.

Langsdorff was warned of the great numbers of British and French warships hunting for him, but German High Command indicated that all the heavy units were at Freetown or Cape Town. Four British cruisers were known to be off South America, but they were expected to be operating independently either on patrol or escorting merchant ships. Alone, each was no match for Graf Spee. Langsdorff headed for the newly discovered British shipping route, and planned to intercept a convoy of four ships that would sail from Montevideo without escort on December 10.

On December 11, Graf Spee's seaplane took off for its usual dawn patrol, sighting nothing. But the plane suffered another in a series of cracked engine cylinders, and Graf Spee was fresh out of spares, so Langsdorff would no longer have the benefit of his eyes in the sky.

December 13, Graf Spee reached the point 300 miles from Montevideo where she expected to find her final four victims. The lack of aerial recognizance caused Graf Spee's luck to run out: dawn broke, but no merchant ships were sighted. Instead, at 0552, two, and then four masts broke the horizon. Graf Spee went to action stations at 0600, and by 0610 her lookouts had correctly identified the newcomers: the heavy cruiser HMS Exeter, and the light cruisers HMS Ajax and HMAS Achilles.

Outnumbered and with a speed disadvantage of seven knots, Graf Spee had no chance to outrun her opponents. Langsdorff turned his ship at the British cruisers, ran his ship up to 24 knots (the most it could do with a fouled bottom), and engaged the enemy. The raiding cruise of the Graf Spee was about to come to a dramatic end at the Battle of the River Plate.

The important of naval air reconnaissance cannot be under-stressed. The old adage, "Look, before you leap" if not followed is often fatal. With today's over-reliance on even more mechanically unreliable helicopters than fixed-wing seaplanes, the chances of a repeat of the fate of the Graf Spee are high. www.bobhenneman.info/bhbrp.htm

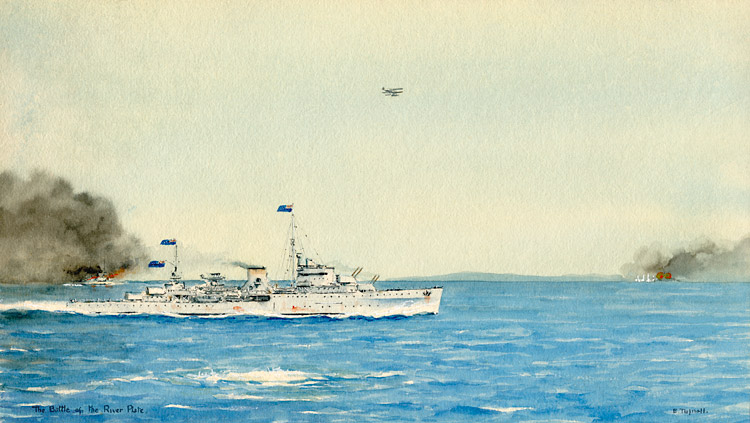

Battle of the River Plate

Near the end of a successful raiding cruise the panzerschiff Graf Spee, under the command of captain Langsdorff and searching for merchant ships sailing from Montevideo to the UK via Freetown, was some 150 miles east of the estuary of the River Plate. Her lookouts spotted masts on the horizon at 0552, off the starboard bow. These were the masts of British warships--not unarmed merchant ships. Graf Spee went to action stations, and turned to engage, as the lookouts at first identified at least two of the newcomers as destroyers. Near the end of her cruise, Graf Spee no longer had to avoid enemy warships at all costs, and Langsdorff planned to engage and disable any warship capable of shadowing his ship. Destroyers were ships Graf Spee could not hope to outrun, but could easily destroy. More importantly, destroyers were used to escort convoys. The German lookouts soon corrected their mistake, identifying the heavy cruiser HMS Exeter at 0600, and correctly identifying two light cruisers by 0610. But Langsdorff continued the approach, knowing that he could not outrun, but did outgun, the British ships.

The British warships were under the command of Commodore Henry Harwood, along with a fourth ship under Harwood's command, were collectively known as Force G. Harwood had previously had his ships spread out to cover a wide area of the ocean: The light cruiser HMS Ajax watched the River Plate estuary, the light cruiser HMAS Achilles patrolled further north off Rio de Janeiro, while the heavy cruisers HMS Exeter and HMS Cumberland guarded the Falkland Islands to the South. Harwood flew his flag from the Ajax, to be closest to the center of the patrol areas.

Graf Spee had attacked the Doric Star some 3000 miles from Harwood's patrol area on December 2, he was certain that the raider would return to the rich hunting grounds of the River Plate-UK shipping routes, on which the Germans previously enjoyed success before diverting to the Indian Ocean. Alone, none of Harwood's three operational ships could hope to defeat the Graf Spee, but together they were more than capable. Harwood did some calculations from Doric Star's location when attacked, and figured that the Graf Spee could reach the waters off Rio by the 12th, the River Plate area by December 13, or the Falkland Islands by the 14th. Harwood gambled that the raider's captain would prefer to intercept merchantmen sailing to the UK than to avenge his ship's namesake by attacking the Falklands, and further deduced that the traffic off Montevideo/ Buenos Aries was more tempting that that off Rio, so he planned to concentrate his ships off the River Plate.

He sent his orders out on December 3: Ajax and Cumberland were to seek and capture the SS Ussukuma, a German freighter in the area capable of resupplying German raiders. Following this interception on the 5th, where the German ship was intercepted but managed to scuttle itself to avoid capture, Cumberland would return to Port Stanley in the Falklands to perform refit and repairs to herself as best she could due to boiler problems. Exeter would leave Port Stanley on the 9th, and the three operational ships would meet at a point 150 east of Montevideo on December 12.

The next morning, the three ships were steaming in line ahead, at the moderate speed of 14 knots, patrolling roughly east-northeast. Like his German counterpart, Harwood did not have his recognizance aircraft patrolling, though for different reasons. While the German plane was inoperable due to a design flaw (the Arado 196 tended to land fast and hard, splashing cold water up on the engine that cracked the hot cylinders, so eventually the ship simply ran out of spares and what cylinders could be cannibalized from the spare aircraft), the British commander simply chose not to operate his.

Harwood had guessed right: soon after dawn his lookouts spotted smoke on the horizon, caused by Graf Spee's diesel engines, which were badly in need of overhaul. At 0604 Exeter reported sighting smoke, and at 0616 signaled, "I think it is a pocket battleship." Thanks to the trickery of the Germans, the British did not know if the vessel they were about to engage was Graf Spee or Admiral Scheer.

Langsdorff was faced with three opponents, the slowest of which had a speed advantage of seven knots over his tired vessel. Avoiding combat was not an option, so the question became how to best engage his numerically superior, but smaller-gunned opponents. He could turn away and keep his distance as long as possible, firing his 11.1" guns at long range, hoping to disable at least one of the enemy vessels before they could get into range to reply, and then use the superior weight of his larger guns to disable or drive the remainder off. But in doing so he would waste tremendous amounts of his limited ammo: hits were rare at long range, especially firing only the three guns of the aft turret, and he might expend all 300 shells in the aft magazine without disabling all three British cruisers. So instead, Langsdorff ran toward the enemy at full speed, closing to 20,000 yards, and then turned broadside to bring all six main guns and half his secondary guns to bear, hoping the greater weight of fire at shorter range would more quickly tell on the most powerful British ship, Exeter. At 0618, Graf Spee opened fire, expecting her weakly armored and armed opponents to shadow or retreat.

Harwood also had a choice to make. He had no plans to shadow, as attack to end the raider's days was his only option, but he could attack in one of two ways. He could keep his ships together to face his more heavily armored and armed opponent as a single group, or he could split them up and attack from two angles, but risk putting one of his ships in a position where it might face the superior German one-on-one. With a great speed advantage and in a daylight action, Harwood chose to divide his ships into to divisions: Ajax and Achilles would close one flank, while Exeter attacked on the other. He had previously communicated these instruction to his captains, so as soon as the enemy was sighted on a bearing of 320 degrees, Captain Bell took Exeter off at high speed on course 280 degrees allowing all three main turrets to bear on the stern of the enemy, while Captains Woodhouse and Parry took Ajax and Achilles to full speed on course 340 degrees.

Ajax led, with Achilles 800 yards behind, as the two smaller ships converged with Graf Spee's bow.

At 0620, Ajax and Achilles returned Graf Spee's fire at a range of 19,200 yards, and a minute later Exeter followed suit, at a range of 19,400 yards. Their fire was coordinated by radio from Ajax.

Graf Spee drew first blood, though her gunnery officer underestimated Exeter's protection and ordered High Explosive, impact-fused shells instead of Armor Piercing. Her third salvo straddled Exeter and scored one hit, amidships where it killed the crew of the starboard torpedo mount and disabled both of Exeter's Walrus seaplanes, denying Harwood their use during the battle. A few seconds later, another shell struck the heavy cruiser, passing through the deck and out the side of the ship near "B" turret--without exploding. Soon a third hit, from the German's eighth salvo, struck the front of "B" turret, putting it out of action and sending splinters across the bridge, killing everyone except the captain and two other officers, all of whom were wounded. The wheelhouse was damaged also, severing communication with steering and engineering; the ship went out of control, and fell off to starboard. Captain Bell, bleeding from a wound to the face, set up command in the secondary conning position and passed orders with messengers, getting his ship back on course. Meanwhile, two more shells struck the ship forward, one of which blew a six-foot by eight-foot hole in the bow after striking an anchor, the other of which started a fire in the forecastle. Soon another sprayed splinters across "X" turret, temporarily disabling it. In exchange, Exeter's gunners scored but on hit on Graf Spee, which struck her control tower killing several officers and instrument operators, damaging communications, and destroying the main rangefinder.

By 0630, Ajax and Achilles had closed to nearly 13,000 yards, putting out a great volume of shells with their smallish but rapidly-firing guns. Langsdorff was obliged to shift targets, giving Exeter a reprieve while he turned his guns on the light cruisers. With communications down and the main director gone, the turrets fired on local control. The secondary guns, 5.9" and 4" weapons, had engaged the light cruisers--but scored no hits.

The British cruisers changed course rapidly, weaving in and out, avoiding the German shells and suffering only light damage from the splinters of near misses. Exeter fired off her starboard torpedoes and the Germans altered course 150 degrees to port at 0636, under cover of a smoke screen, to avoid them and open the range from Ajax and Achilles to 17,000 yards. The secondary guns continued to target the light cruisers, but main gun's fire shifted back to Exeter. Freed from heavy fire, Ajax flew off her spotter aircraft, only to find that radio difficulties prevented communications with it.

The British heavy cruiser scored a second hit on Graf Spee, but soon began to suffer. An 11" shell slammed into the deck near a firefighting team, causing many casualties. Bell swung his ship to starboard, to bring his port torpedoes to bear. Three more 11-inch shells found their mark, one destroying "A" turret, one causing heavy casualties in the armament office, and the third passing through the ship's side and three bulkheads before blowing a twelve-foot by sixteen-foot hole in the chief petty officer's quarters.

Exeter was in bad shape. Fires raged all over the ship, she had a 10-degree list and was trimmed down by the bows from flooding, communications were down, power was out over most of the ship, and only "Y" turret rained in action. The gyro-repeaters were out of action, so Captain Bell had to con his ship using only a hand compass from a lifeboat. 61 officers and men were killed, and 23 wounded. But the ship kept her speed, and stayed in the fight. A grim faced signalman on Ajax, looking at the burning and listing Exeter, commented to his officer, "It looks, Sir, as if it is going to be another bloody Coronel."

Meanwhile, Graf Spee had continued to be target to the light cruisers' guns. Many simply ricocheted off her armor belt, and Harwood later commented that, "We might as well have been throwing snowballs at her." But the rapid fire of the 6-inch guns was having more effect than Harwood thought, and Graf Spee was suffering many casualties among the crews of her weakly protected secondary battery. Rather than press home his advantage and attempt to finish off the British cruisers, Langsdorff decided to open up the range: he had not expected the inferior British ships to slug it out at short range, and he was suffering more damage and casualties than was acceptable: his ship, after all, still had to get past the Home Fleet and travel 12,000 miles to get to the nearest friendly base.

Graf Spee continued to swing around to the west, and Harwood feared that she would double back and finish off Exeter, so he turned west also to once again close the range with his light cruisers. Exeter suffered a short-circuit which eliminated her last turret from action. She was now a lame duck, and her crew watched the battling ships disappear over the horizon.

Graf Spee turned her fire once again to the smaller ships, while continuing westward to try to keep the range open. At 0720, Langsdorff swung his ship to port to bring all guns to bear again. 6-inch shells found their mark, starting fires on Graf Spee. Achilles was straddled by a salvo of large shells, splinters from which damaged the control tower, killed several officers and men, destroyed the wireless gear, and wounded Captain Parry. Ajax fired her torpedoes, but Graf Spee sighted them and took evasive action. Her 11-inch guns paid back Ajax for her insolence, with a hit that disabled "X" and "Y" turrets, killing six and wounding 2 before exploding in Harwood's cabin and destroying all his personal belongings. Graf Spee's own torpedoes were fired from her starboard tubes. Radio communication had been established finally with Ajax's Seafox spotter plane, and it signaled, "Torpedoes approaching; they will pass ahead of you." Harwood altered course, and the torpedoes sped by harmlessly.

The British guns continued to blaze, but it appeared that they were incapable of stopping Graf Spee. Ajax's guns had fired 3-400 rounds in rapid succession, and they would no longer return to the load position under recoil. The gun crews poured oil onto them and pushed them back by hand. "B" turret's ammo hoist failed, leaving her with only three operational guns. With the faster British ships closing the range to only 8000 yards, it appeared that they were coming out on the loosing end of the fight. Harwood learned that Ajax had fired 80% of her main rounds, and had to assume that Achilles was similarly short. Fearing that Graf Spee would turn and destroy first one, and then the other light cruiser, he fell back to break off the day action. He decided to shadow until dusk, lick his wounds, and try again after dusk. The British cruisers dropped back, a final hit from Graf Spee carried away Ajax's topmast, eliminating her wireless communication. Harwood made smoke and turned away at 0740, and eventually dropped back to 15 miles, one cruiser on each quarter of the Graf Spee. Captain Parry overestimated Graf Spee's speed, and accidentally closed to 23,000 yards at 1005, only to rapidly open the range under cover of smoke when two salvos from Graf Spee fell close alongside.

Langsdorff, however, had no desire to continue the action, even though he was sure that Exeter was sinking. Graf Spee had fired 60% of her ammo, and was still at a considerable speed disadvantage, so the British cruisers could remain at extreme range until the Germans ran out of ammo. His ship was also more seriously wounded than Harwood thought, having been struck 17 times. He himself was injured, being knocked unconscious by an exploding shell and cut by splinters from two other. Graf Spee was also short of ammo, so Langsdorff made occasional smoke as he retired to the west, making no attempt the turn on his pursuers. He received damage reports from all over the ship, did a tour of his command. What he found distressed him: a six-inch shell had penetrated the starboard quarter, destroying an ammunition hoist and cutting the electricity to the forward 11" turret; another had passed through the ship leaving a three-foot by six-foot exit wound as it passed out the port side; a third destroyed a 4" gun and its ammo hoist. A 5.9" mount, the ship's galley, the main rangefinder and the radar were destroyed by shellfire, and fire had destroyed the scout plane, three of the ship's boats, and Langsdorff's cabin. The onboard plant to purify her diesel fuel for her engines was damaged beyond repair, there were six leaks below the waterline, and a shell had wrecked the bridge as it passed through without exploding. There were 36 dead and 59 wounded, and there was much repair work to be done before the ship could attempt the long voyage home. Langsdorff told his navigator, Jurgen Wattenberg, "We must run for port, the ship is no longer seaworthy."

But where to go? The two only two choices were Buenos Aries or Montevideo. Both nations were neutral, but Argentina had better relations with Germany while Uruguay leaned towards the U.S. and UK. Many authors have criticized Langsdorff for choosing Montevideo; some even claiming his judgment was impaired due to his being in shock from his wounds. Perhaps Argentina would be friendlier, but it was not a good choice for several reasons. For starters, Montevideo was simply much closer. Secondly, the waters of the River Plate are some of the most dangerous in the world, and the estuary is littered with literally thousands of wrecks; Graf Spee would have to stop to take on a pilot, unthinkable with the British close behind. Also, the Panzerschiff drew 22 feet of water, even without any damage. This meant that she would have to stay in the narrow dredged channel to reach Buenos Aries, while the British cruisers, which drew only 16 feet, would have freedom of movement. The channel was only 23 feet deep at some places, so if the British scored a hit below the waterline Graf Spee would ground, unable to move. Even if she did not run aground, the German ship's water intakes for the cooling system of her diesels were at the lowest part of the ship's bottom, and any mud sucked in would cause the tired engines to overheat very quickly, immobilizing the ship. Disabled or stuck, Graf Spee would be easily destroyed, but would not sink, allowing the British to capture her. Buenos Aries was out; the ship would head for Montevideo. Langsdorff sent a brief action report to German High Command, and announced his intention to enter Montevideo. Admiral Raeder replied in agreement with the plan.

Langsdorff sent someone to check on his prisoners, 62 British officers and seaman who had escaped injury in their compartment deep within the ship. They were fed, and all breathed a sigh of relief at their mixed blessing: while they had wished the Royal Navy victory, the destruction of the Graf Spee would have meant their deaths. They were not yet free, but they were alive.

Harwood dispatched the Seafox to check on Exeter around 0800, fearing the worst when she failed to respond to calls from Achilles. The plane found Exeter, which signaled that she was hit hard and, was ablaze amidships, but not in need of immediate assistance. When Exeter finally rigged up some wireless equipment, Bell reported, "All turrets out of action. Flooded forward up to No. 14 bulkhead, but can still do 18-knots." She was of no further fighting value, so Harwood ordered her to Port Stanley. With some luck and fair weather, she would make the 1000-mile voyage without sinking.

Cumberland was ordered to leave the Falklands immediately to replace Exeter. The order came at 0916, and by 1000 she was clearing Port Stanley. Captain Fallowfield had put his ship's boilers back together and raised steam on his own initiative when he heard radio signals of the battle, and raved to the Plate area at best speed. He would arrive in 36 hours.

At 1104, Graf Spee sighted a merchant ship, the British steamer SS Shakespeare bound for the UK of Montevideo. Langsdorff altered course to intercept, intending to sink the ship with a torpedo as he went by and claim one last victim. Always chivalrous, Langsdorff signaled his intention to the steamer's captain, telling him to abandon ship, and also to Harwood, asking him to "Please pick up lifeboats from British steamer." The German captain used his ship's correct call sign, and for the first time the British knew what ship they had been fighting. Shakespeare's captain hove to, but did not abandon ship. Without the time to wait, and never being one to sink a vessel with unarmed sailors on board, Langsdorff turned Graf Spee back towards Montevideo without firing. [EDITOR: apparently a decent man and not a Nazi?]

Harwood signaled the British Naval Attaché' in Buenos Aries at 1347, saying that the German warship was heading towards the River Plate area. His cruisers continued to follow the German ship as it headed for Montevideo. At 1543 that afternoon, Achilles sighted a ship that was identified as a Hipper class heavy cruiser. For 20 minutes Harwood and Parry wondered how they could possibly face German reinforcements, until lookouts corrected their error and identified the ship as the British steamer SS Delane, who's streamlined funnel resembled those of German cruisers.

Late in the afternoon, long before any ships were sighted, the thunder of distant gunfire was heard in Punta del Este, on the northern edge of the River Plate estuary. The flagship of the National Navy, the 1,150-ton gunboat Uruguay under the command of Captain Fernando J. Fuentes, sailed out to investigate. The rest of the National Navy (consisting of three other gunboats) went on alert, ready to defend the nation's territorial waters and enforce International Law. While these craft with their diminutive guns were no match for a large warship in the open ocean, their shallow draft and torpedoes gave them an advantage in the estuary. Around 1800 hours, Uruguay's lookouts spotted Graf Spee, and settled in to watch the action.

The coast of Uruguay was sighted at around 1815, and by 1900 Harwood guessed that Graf Spee intended to enter the River Plate estuary. He ordered Achilles to follow Graf Spee into the wide estuary of the river, International Law allowing "hot pursuit" to override the respect for neutral territorial waters, while Ajax turned south to prevent the Germans from suddenly doubling back. At 1915, Graf Spee suddenly turned broadside and fired two salvoes at Ajax at the range of 26,000 yards, causing the cruiser to turn away and make smoke. At 2048, just after sunset, Graf Spee fired three salvoes at Achilles, compelling that vessel to keep her distance and reply with five salvoes of her own. In the gathering darkness Parry had to close to keep Graf Spee in visual range, and increased speed to get within 10,000 yards. Graf Spee fired three salvoes between 2130 and 2145, but Achilles did not back off. Parry could clearly see the silhouette of the German warship against the lights of Montevideo, and reported just before midnight that Graf Spee had dropped anchor. A quick estimate of the repairs needed for the long voyage home was two weeks, so the Germans needed an extended stay in Montevideo.

A few minutes late, a German officer unlocked the door to the compartment that held the British prisoners and told them that Langsdorff would release them in the morning. Under International Law, Graf Spee could not hold prisoners and claim "havarie," the privilege of sanctuary for damage caused at sea.

The British cruisers took up station in two separate channels along the 136-mile wide estuary, hoping that Graf Spee would stay put, as they were in no position to stop her. Ajax had half of her guns out of action, and had only enough ammo to keep the others in action for 30 minutes. Achilles had suffered only splinter damage, but carried only enough ammo for 15-20 minutes. The closest reinforcement, Cumberland, was still 24 hours away. Harwood would not be deterred; he informed his officers and crews that in the event of Graf Spee's sudden exit from harbor his policy was "destruction," prompting someone to mutter "Whose?"

Reinforcements were on the way, with Cumberland already en route and scheduled to arrive the next day. The battlecruiser Renown, the carrier Ark Royal, and the cruiser Neptune were a thousand miles away off the north of Brazil, and the heavy cruisers Dorsetshire and Shropshire were dispatched from Cape Town to arrive in 5 days time.

While the diplomatic and legal maneuvering began in Uruguay, there was celebration back in Britain. One of the few German heavy ships, and one of the most successful raiders, had been tracked down, engaged, and driven to harbor by inferior forces operating in the best tradition of the Royal Navy. Harwood was an instant hero, and was promoted instantly to Rear Admiral and awarded the Knight Commander of the Order of Bath (KCB), while Bell, Parry, and Woodhouse were awarded the Companion of the Order of Bath (CB).

Before daylight on the 14th, the German Minister Dr. Otto Langmann boarded the Graf Spee. He chastised Langsdorff for not going to Argentina, where the political climate was friendlier and Langmann's job would have been easier: while there was an active pro-Nazi minority in Uruguay, the vast majority of the people disliked authoritarianism and were profiting from trade with Britain.

General Alfredo Baldomir, President of the Republic of Uruguay, and his ministers of Foreign Affairs and Defense, Dr Alberto Guani and General Alfredo Campos, prepared to hear arguments from the British and German ministers before they decided the fate of the warship they now hosted in their harbor. At issue was the interpretation of the Hague Convention of 1907, the relevant International Law. This law stated that a belligerent warship could only stay in a neutral port for 24 hours before that neutral power was obliged to intern it for the duration of hostilities. However, a warship could extend their stay past 24 hours if it claimed "havarie," or the right of sanctuary, because it had suffered damage while at sea. If damage had been suffered, then the neutral power could not force the warship to go to sea until repairs were complete.

Langmann argued his case, pressing for the 15 days Langsdorff said it would take to make repairs to allow the Graf Spee to make a breakout, followed by a run past the Home Fleet for Germany.

The British minister, Eugen Millington-Drake, argued that because Graf Spee had sailed 300 miles at good speed to Montevideo after the battle she was indeed seaworthy, and should not be granted sanctuary for repairs that were to make the ship battleworthy--not seaworthy.

Guani and Campos listened to both sides, and decided not to decide. President Baldomir could not ignore the pro-German element of his population, but did not want to upset relations with either Britain or the pro-British USA, Uruguay's two largest overseas trading partners. They informed the German minister that Uruguayan technical experts would board the Graf Spee to inspect her damage and make their own estimates for repair. They also reminded the British minister that the British cruiser Glasgow had claimed "havarie" after the Battle of Coronel in 1914 and spent a week in drydock at neutral Rio de Janeiro.

Langsdorff kept his promise, and ordered all prisoners released. The British merchant captains Dove and Pottinger went to pay their respects and say goodbye to the German warrior, who had acted more as a host than a captor. Langsdorff greeted them, and gave each of them a cap tally from one of Graf Spee's dead, apologizing that they had been on board for the battle and expressing thanks that none of the British merchant seamen had been injured. A the British merchant officers and seamen mustered on the quarterdeck to be dismissed by the master-at-arms, they passed 36 coffins sitting under the guns of the aft turret; not everyone on Graf Spee had been as lucky as they.

Soon after Langsdorff freed his prisoners in the afternoon, and landed his dead and wounded for hospital treatment, the technical experts toured the ship. They inspected and prepared a report, which they forwarded to Guani and Campos. As they reviewed the report to reach a decision, the British minister, Millington-Drake, interrupted with a request to see them again. It would appear that the British minister had forgotten two of the golden rules of diplomacy: "Be careful what you ask for, because you just might get it." and "for expert advice, ask an expert."

Harwood, knowing that his beat up ships stood little chance of prevailing twice without reinforcements, refueling, and a fresh load of ammo, did not want Graf Spee turned out of Montevideo anymore than Langsdorff did. He needed a few more hours for Cumberland to arrive to give him a fighting chance, and more time past that for Renown, Ark Royal, and the other cruisers to reach the scene. Harwood asked Millington-Drake to use "Every means possible" to DELAY Graf Spee's departure! Harwood needed exactly the opposite of what the British minister had been fighting for.

Harwood's idea was to take advantage of the very law that Millington-Drake had wanted to use to expel Graf Spee from neutral waters. The Hague Convention had a clause in it to protect unarmed merchant ships from raiders: if a merchant ship belonging to a belligerent power left a neutral port, then a warship belonging to the other could not leave that same port for 24 hours, thus giving the merchant ship a fair chance to avoid capture.

Millington-Drake's naval advisor McCall quickly arranged for the British steamer SS Ashworth to leave Montevideo at 1800 on the 15th, and the minister went in to reverse his arguments to the Uruguayan ministers. Guani and Campos made their decision: Graf Spee could not sail before 1800 on the 16th, but had to sail before 2000 hours on Sunday the 17th.

Meanwhile, the crew of the Graf Spee had been busy. Repairs had been started as best they could be, as Montevideo's one shipyard and all local firms refused to help. Some local workers of German origin volunteered, as did the crews of two German merchant ships in harbor. A few civilian technicians from Argentina came to assist also, employed by the German Naval Attaché to Buenos Aries. But the crew of the Graf Spee labored not as men celebrating a victory over British warships, but as men preparing for a battle they knew they could not win.

In the evening of the 14th, Langsdorff met with his officers. The pro-Allied government must not intern the ship, nor could it fall directly into British hands. He intended to attempt a breakout at night.

The next morning Graf Spee buried her dead in a funeral attended only by a few of the crew and a handful of petty officers, as everyone else was busy working on the ship. A naval band let the procession from the dock to the Northern Cemetery on the outskirts of Montevideo. Crowds lined the streets to see the spectacle, including many of the British seamen formerly held on Graf Spee. In a scene that seems out of place in the 20th century, enemies approached each other and exchanged best wishes and handshakes.

After giving a short eulogy at the gravesite, Langsdorff walked down the row of caskets sprinkling dirt on each one. At the end of the row, he came face-to-face with captain Dove, who stood saluting his former captor. Langsdorff paused, looked him in the eye, and stood at attention to return his salute. Dove left a wreath, which said "To the brave memory of the men of the sea from their comrades of the British Merchant Service."

As a last salute to the fallen Germans was given, photographers immortalized the moment: Everyone stood with their arm outstretched in the Nazi salute, except Langsdorff who gave the traditional salute of the old German Navy. All eyes were on the graves, except minister Langmann's, who glared disapprovingly at Langsdorff.

The propagandists on both sides were distressed by this moment. The German media had portrayed Langsdorff as a hero dedicated to the Reich and its leader, boldly standing exposed on the highest point of the conning tower despite his wounds as he won a victory akin to Coronel. They also reported that the British had spat upon the coffins of the fallen German heroes along the funeral route. Their propaganda efforts went out the window when the crew of the Graf Spee vehemently denied these charges, and the photos of the funeral were splashed across the front pages of the world's newspapers.

British propagandists were equally annoyed, as their attempts to paint all Germans as heartless villains were dispelled by Captain Dove's radio interviews about how chivalrously the British sailors had been treated.

But British propagandists made up for their errors by spreading reports that Royal Navy reinforcements had arrived. As the Uruguayan Government informed the German minister of the 72-hour limit, radio reports told of the arrival of Renown and Ark Royal (actually still off Brazil), plus the French battlecruiser Dunkerque. With the departure of the SS Ashworth, Graf Spee's window to leave Montevideo narrowed to just one day. Langsdorff's hopes of a surprise exit from harbor that night were gone. To make matters worse, one of Graf Spee's lookouts sighted a large ship off the Plate, which he incorrectly identified as Renown.

The German Captain met with his crew, which one officer recorded in his diary as being ready to follow their captain blindly, even to certain death. Langsdorff told some of his sailors that he would fight if he could, but if he could not he would not let Graf Spee and her crew "become a target in a shooting match". One of Graf Spee's engine-room mechanics recorded Langsdorff's famous words to the effect that he would not let his ship be shot to pieces by a greatly superior force, and that to him a thousand young men alive were worth more than a thousand dead heroes. [AMEN].

Langsdorff reported back to Berlin: he was trapped, could not leave until at least 1800 on the 16th, and would be interned at 2000 on the 17th.

The German Captain continued, "no prospect of breaking out into the open sea and getting through to Germany. If I can fight my way through to Buenos Aries with ammunition remaining I shall endeavor to do so".

But Langsdorff knew that all of the reasons why Buenos Aries was a bad choice still held true, and that he had no hope of disabling Ajax, Achilles, and Cumberland, let alone Renown and Dunkerque, with his remaining ammo, a mere 20-30 minutes supply.

As this course of action, "might result in destruction [of Graf Spee] without possibility of causing damage to the enemy, request instructions whether to scuttle the ship...or to submit to internment".

The German minister, Langmann, commented, "I regard internment as the worst possible solution. It would be preferable in view of shortage of ammunition, to blow her up in the shallow waters of the Plate and to have the crew interned." The German minister pressed for another extension, but under pressure from the British Guani and Campos held firm.

The message was sent to Admiral Raeder, who consulted with Hitler, who forbid internment. Raeder answered "Attempt by all means to extend time in neutral waters", and responded to the plan to attempt to fight through to Argentina "Approved." It stressed "No internment in Uruguay. Attempt effective destruction if ship scuttled." In other words, as long as the ship was not interned, the decision was up to Langsdorff. The Captain then met with his officers to discuss options. There was a slim chance that the ship could make Buenos Aries without being destroyed, grounding in the channel, or being disabled by mud in the cooling system, but no guarantee that the government of Argentina would be any more willing to let Graf Spee stay past 24 hours than Uruguay had. But then the whole discussion became pointless: as a final insurance against a surprise exit by the German warship, the British steamer SS Dunster Grange had sailed from Montevideo: Graf Spee could not leave before 1800 hours Sunday. With only a two-hour window, there would be no chance to surprise the waiting British by leaving early.

The die was cast. On the night of the 16th, repair work on Graf Spee was halted. She was filled with the sounds of hammering and small explosions, as the fire control installations, radios, radars, and other equipment were blown up. Dials and electronics were smashed with hammers, gun elevation gear was destroyed, and the breach blocks from the main guns were removed and tossed overboard. The British would learn nothing when they boarded the wreck, and Graf Spee's guns would never be used against Germany. Secret documents were destroyed, and the ship's bell, battle ensign, the portrait of Admiral Graf von Spee, and other historically significant items were sent ashore to be carried home in a diplomatic pouch. Powder charges were stacked inside the turrets around a torpedo warhead, flash doors were opened, a torpedo was wired in the engine room, and detonator wires were rigged. Langsdorff instructed that the wires be run to the conning tower, where he would set them off manually. But his officers insisted that he must look after his men, and rigged up a timer instead.

As live radio carried real-time reports to the world, an estimated three-quarters of a million people crowded along the cost to watch the Graf Spee depart and face the waiting British. Tuning in to the radio reports was Harwood, who heard that men and equipment were being transferred from Graf Spee to the German tanker Tacoma. The German Naval Attaché learned that Renown and Ark Royal were still two days away, refueling at Rio, but it made no difference; British warships still hovered outside the channels, and Graf Spee had no chance of escape.

At 1830 Graf Spee ran up two large battle ensigns and weighed anchor. 700 of her crew had been transferred to Tacoma, which under Captain Hans Konow weighed anchor as well, following about a mile behind the warship as she entered the South channel to the sea. Just outside the breakwater, Tacoma stopped and transferred the German sailors to the Argentine tugs Gigante and Coloso, which had been hired out of Buenos Aries. The Uruguayan National Navy quickly turned Tacoma back into Montevideo where she would be interned for the duration for the war, as she had sailed without proper authorization and assisted in a hostile act.

In the south channel, just outside Uruguay's then three-mile territorial limit, Graf Spee swung west, turned out of the dredged channel, and dropped anchor. The timers on the charges were set for 20 minutes, and the order to abandon ship was given. Langsdorff and the last five officers hauled down the ship's ensigns, made sure the remaining crew was safely off, boarded the captain's launch, and moved about a mile away.

Just before sunset, Graf Spee shuttered from the powerful explosion of the torpedo warhead in her engine room. A second later she was ripped apart in a tremendous explosion. Her rear turret was blown clear of the ship, the stern was severed, and flame belched high into the sky. The forward turret did not explode, probably because the initial explosion damaged the firing circuit. But the ship was in flames from one end to the other, and quickly settled into the shallow water with her main deck awash. The fires would burn for two days.

Langsdorff ordered the final entry into the Graf Spee's log: "Graf Spee put out of service on December 17, 1939, at 2000 hours."

Langsdorff and the rest of the crew would reach Argentina, where the German community greeted them with hospitality, fresh fruit, and warm bread. But the Argentine Government's reception was not so warm. Confirming the suspicion that Graf Spee was no more welcomed there that in Uruguay, the officers and crew were not treated as shipwrecked sailors, but were rounded up and interned for the duration of the war. 16 officers escaped in the next two months, and 17 more in August, and a handful in 1942. A few ratings also escaped, and like the officers managed to return to Germany via a variety of routes, including through Japan and the Soviet Union. But the rest went to prisoner of war camps when Argentina joined the Allies in 1943. Six officers and 894 ratings were repatriated in February 1946, aboard the British liner Highland Monarch, fittingly enough escorted by HMS Ajax, while 168 chose to stay. Hundreds more returned, and some 500 of Graf Spee's crew eventually settled in Argentina.

Langsdorff was attacked in the press as a coward and criticized for not going down with his ship. He met with his crew one last time, telling them what the papers were saying, and that he had not lacked the courage to make a final stand, but rather had known that such a stand would have pointlessly killed many if not all of his crew. Dismissing approaching reporters he returned to their billet with his senior officers, were Langsdorff enjoyed their company until about midnight. Going back to his room, he lit a fine cigar, poured a glass of a favorite Scotch, and wrote a letter each to his wife, his parents, and the German Ambassador. After sealing and addressing the letters, Langsdorff spread the Graf Spee's battle flag out, laid on it, and shot himself in the head.

The next afternoon, he was laid to rest in Buenos Aries, at a funeral attended by his officers, crew, and Argentinean officials. SS Ahlea's Captain Pottinger, attended to represent the British merchant sailors once held captive on board Graf Spee.

British officers boarded the Graf Spee as soon as the fires were out, but found nothing of value. One of the Royal Navy's top divers attempted to enter the forward turret to recover the advanced gyro-firing system (actually destroyed before the scuttle), only to become trapped and drown. The wreck of the Graf Spee slowly sank into the mud, until by 1948 only the control tower could be seen above water. In a few years even that was out of sight, and the Graf Spee was just another of thousands of wrecks in the River Plate estuary.

In 1946, Uruguay extended their territorial waters out to 12 miles, later 200 miles, and Germany relinquished ownership of all wrecks inside territorial waters as part of the surrender agreement, so today the wreck is the property of the Government of Uruguay. One of the ship's 5.9" guns was salvaged in 1999 and put in a park along the harbor at Montevideo.

A major salvage operation was announced by a private German group and the National Navy of Uruguay in late 2003, and work began February 2004 to salvage the Graf Spee, drydock her at the Navy Yard for as much restoration and repair as possible, and turn her into a museum at Montevideo. The control tower and aft turret are the first objectives, to be followed by the complete forward section of the hull.

Therefore, despite the success their seaplane fighter provided them, the Graf Spee's AR-196 seaplane fighter was constantly broken and thus denied their captain and staff the ability to see over-the-horizon (OTH) and spoil enemy recon and air attacks upon them at the end of the mission.

At other times later in WW2, the AR-196 performed well and was even used to capture a British submarine the HMS Seal.

AR-96 seaplane fighters used to capture the HMS Seal in WW2

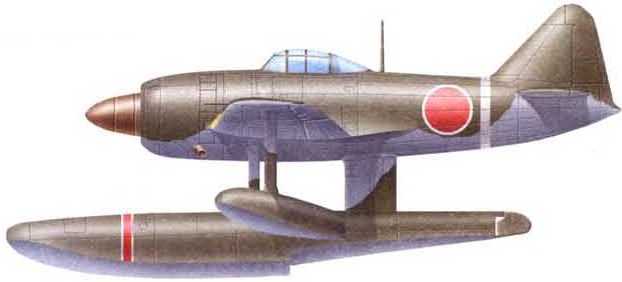

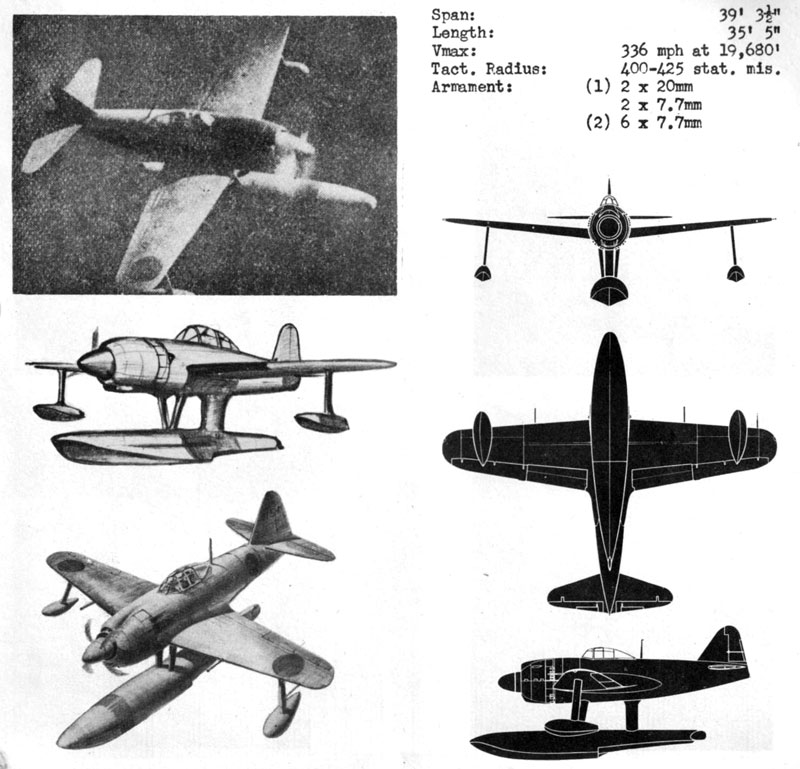

The Japanese had the best seaplane fighters until the advent of the amazing SC-1 SeaHawk by the USN at war's end. The Zero float plane (Allied code-name: "Rufe") was nearly as maneuverable and formidable in dogfights as versions without floats.

Formidable Rufe Seaplane fighter in WW2

Offensively, the lack of a German seaplane fighter enabled British cruisers to use their SeaFox seaplanes to stalk the pocket battleship outside range of her 11" guns and radio-correct in 6" gun strikes with devastating accuracy and then dart back outside of range, and radio-vector help from other ships and planes to corner it. In other words, the pocket battleship without a seaplane fighter that could ward off enemy scout seaplanes and attack other ships beyond her ship armaments cannot shake her followers and break contact. In war, the lighter platform that makes first contact with the enemy as an element independent of the main body must be able to disengage. The USN still hasn't learned this lesson that every individual ship must be self-sufficient as it deludes itself that it will always deploy in mini-fleets (surface action groups) with a bloated super aircraft carrier as base. The USN will claim that helicopters can fly out from destroyers/cruisers to see OTH and can attack with PGMs to be defacto seaplane fighters; but they cannot fly long and far enough without using up limited JP-8 aviation fuel stored--and they cannot ward off enemy fighters.

Piasecki VTDP modified UH-60

Current MH-60 helicopters operating from USN destroyers/cruisers need Piasecki VTDP propellers/wings to increase range, speed and flight duration. AMRAAM armament to shoot-down enemy air threats beyond visual range must be facilitated. Work must be done to MH-60 turbine engines to enable ship's fuel to be utilized to increase air coverage. When F-35Bs become available, the formula to operate them by VTOL from destroyers/cruisers rear flight decks must be ascertained. If none of the above can come to pass within the USN bureaucracy, then armed cropdusters like the FireBoss with floats should be put to sea via catapults and cranes to recover them after water landings. If the USN does not take drastic measures to increase both the quantity and quality of the air cover over its surface ships, in the future it is going to have entire fleets sunk like the individual Graf Spee was sunk in 1939 by enemies who know how to attack from a safe stand-off.

How Seaplane Fighters Sank the Graf Spee

www.fortunecity.com/meltingpot/portland/971/Reviews/interwar/seafox.htm

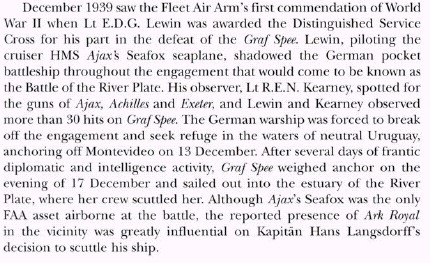

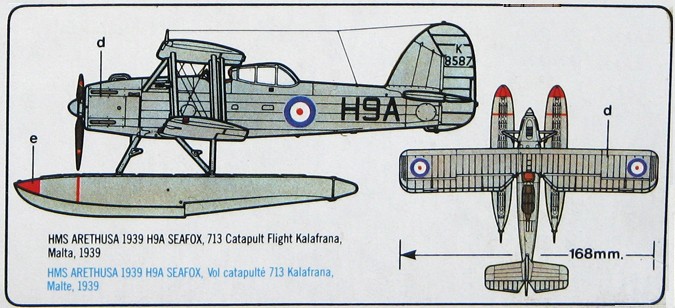

The Seafox's moment of glory came on the 13th December 1939. Flying from HMS Ajax it spotted for the Battle of the River Plate that resulted in the scuttling of the battleship Graf Spee on the 17th. Unfortunately, very little seems to be known about the aircraft. The Ajax carried two Seafoxes probably not camouflaged and possibly K 8581 and K 8582 with the crest of Ajax on the fin. As one was damaged only one spotted but no one seems to remember which or any other details except that Lt. Lewin received the DFC for his efforts and Lt. Kearney was mentioned in despatches. Sixty six aircraft existed, built to specification S11/32 and first flying on 27th May 1936. With a span of 40' and a length of 33' 5 1/2" they were powered by a 395 h.p. Napier Rapier "H" air-cooled engine which proved to be a bit under-powered. It's only armament was a Vickers or Lewis machine gun operated by the observer and it could carry 2 x 100 lb. anti submarine or 8 x 20 lb. bombs under the wings. A couple were also flown with wheels instead of floats.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairey_Seafox

Operational history

In 1939, a Seafox played a part in the attack on the German

pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee by spotting for the naval gunners. This led to the ship's destruction after the Battle of the River Plate.

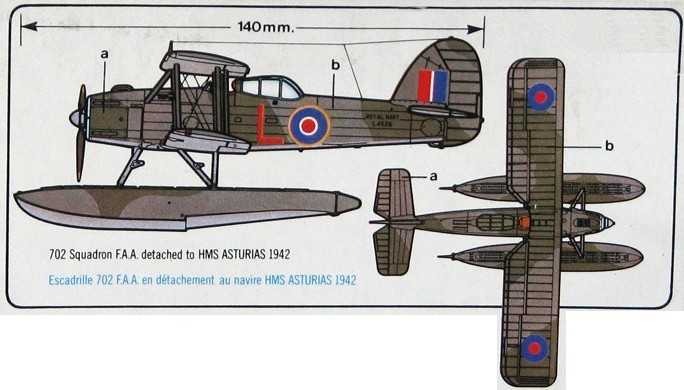

They were utilised up until 1943. The Seafox was operated during the early part of the war from the cruisers

HMS Emerald, Neptune, Orion, Ajax, Arethusa, and Penelope and the armed merchant cruisers HMS Pretoria Castle, Asturias, and Alcantara. The Royal Australian Navy deployed the Seafox aboard the cruisers HMAS Perth, Sydney, and Hobart.Operators

- United Kingdom

Specification

Data from Fairey Aircraft since 1915 [3]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 33 ft 5 in (10.19 m)

Wingspan: 40 ft 0 in (12.20 m) Height: 12 ft 2 in (3.71 m) Wing area: 434 ft² (40.3 m²) Empty weight: 3,805 lb. (1,730 kg) Loaded weight: 5,420 lb. (2,464 kg) Powerplant: 1× Napier Rapier VI piston, 395 hp (295 kW) Performance

- Maximum speed: 124 mph (108 knots, 200 km/h) at 5,860 ft (1,787 m)

- Cruise speed: 106 mph (92 knots, 171 km/h)

- Range: 440 mi (383 nmi, 710 km)

- Service ceiling: 9,700 ft (2,960 m)

- Endurance:4.25 hours

- Climb to 5,000 ft (1,520 m): 15.5 min

Armament

- 1 x 7.7mm medium machine gun

See also

Comparable aircraft

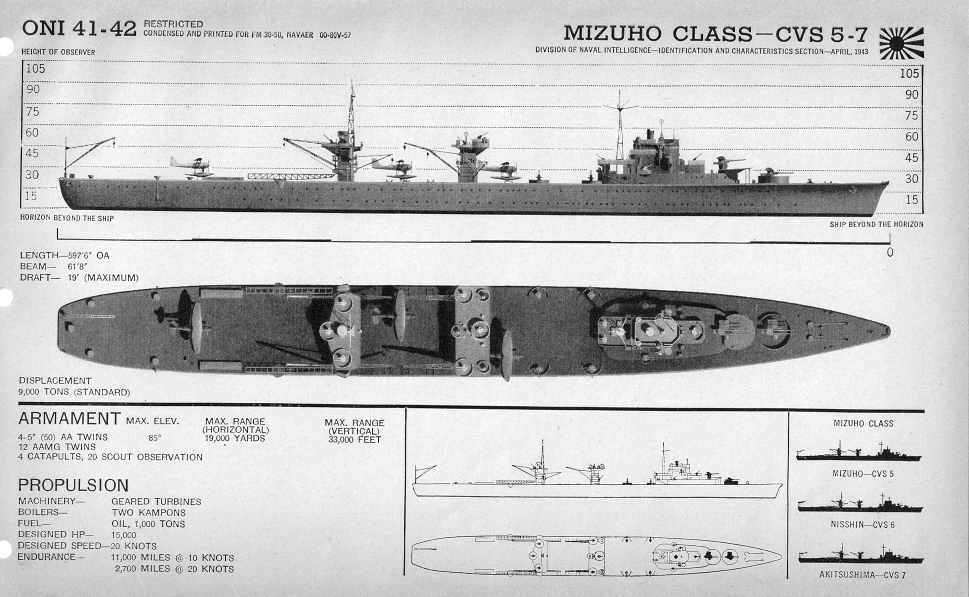

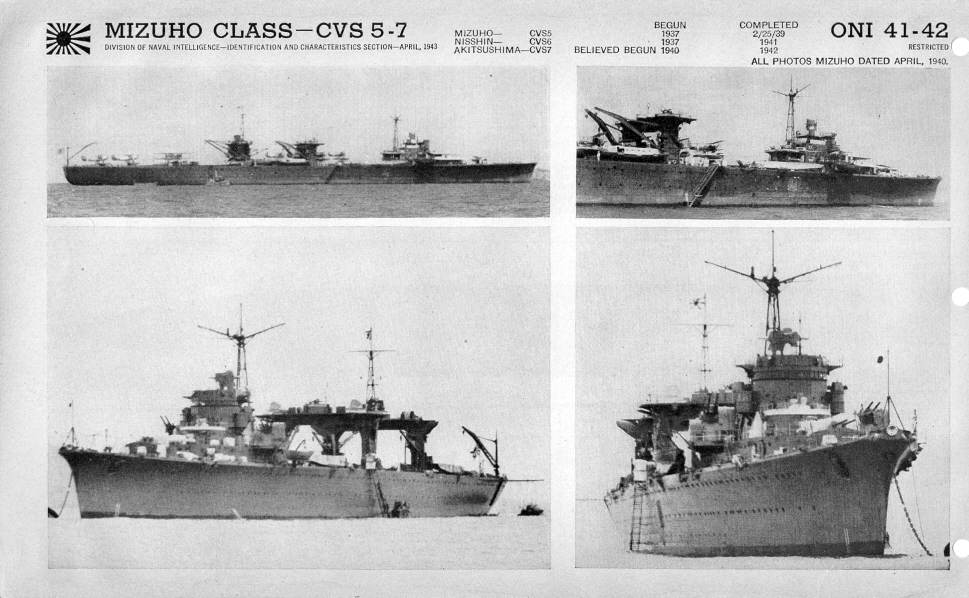

War in the Pacific: The Japanese Soared when they had the Men to Fly

Studying the Japanese in WW2, the common cliche' is that they lost their air power by their aircrews being killed off. What people do not understand who hold to this cliche', is that the Japanese were painfully aware that to control the vast sea areas of the Pacific that they needed to put up every plane they could into the air--and not just by aircraft carriers. The lazy Allies in contrast, were not as aggressive--and are still not resourceful enough today--and this failing led to many early defeats in WW2, until our sheer mass production numbers overwhelmed them.

The Japanese used the following methods to get planes at sea:

1. Aircraft carriers

2. Seaplane carriers ("tenders")

3. Catapult-launched seaplanes from cruisers/battleships

4. Seaplane fighters from coast territories

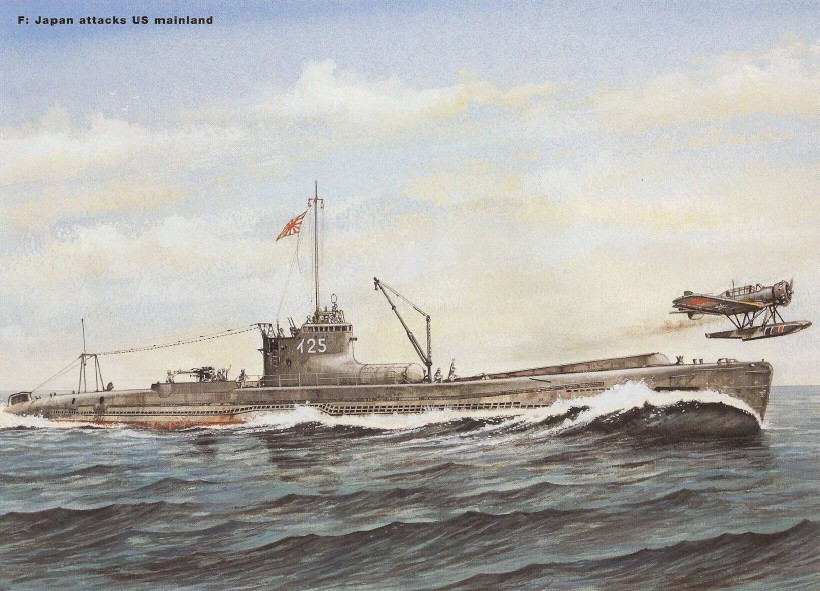

5. Seaplanes from submarines

6. Large seaplane patrol bombers from coast territories

The result of this naval air activity is that the Japanese could nearly always spot the Allied ships and then direct air and sea attacks against them, exploiting their local air supremacy from their aircraft numbers and their long range and very lethal large HE-warhead Long Lance torpedoes. Just one of these torpedoes from the submarine I-19 finished off the U.S. aircraft carrier the USS Wasp after it started fires that couldn't be put out. After Pearl Harbor, Admiral Nagumo's fleet went west to land attack Darwin, Australia and then into the Indian ocean to raid the British ships there that for some reason included the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes--without any aircraft--which was sunk. A catapult launched E-13 "Jake" seaplane from a Japanese cruiser found the British cruisers and tailed them for several HOURS; radioing in swarms of planes from the Japanese carriers to finish them off.

The first question that has to be asked is, WHERE WERE THE CATAPULT SEAPLANES ON THE BRITISH CRUISERS? What were they doing? Research indicates their cruisers probably had bi-plane Walrus type seaplanes that would be at a speed disadvantage to try to shoot-down a monoplane Jake. However, they could have TRIED. The Jake lacked armor protection and only had one 7.7mm medium machine gun in its rear for self-defense there. Maybe their air resistance could have been enough to make the Jake go away?

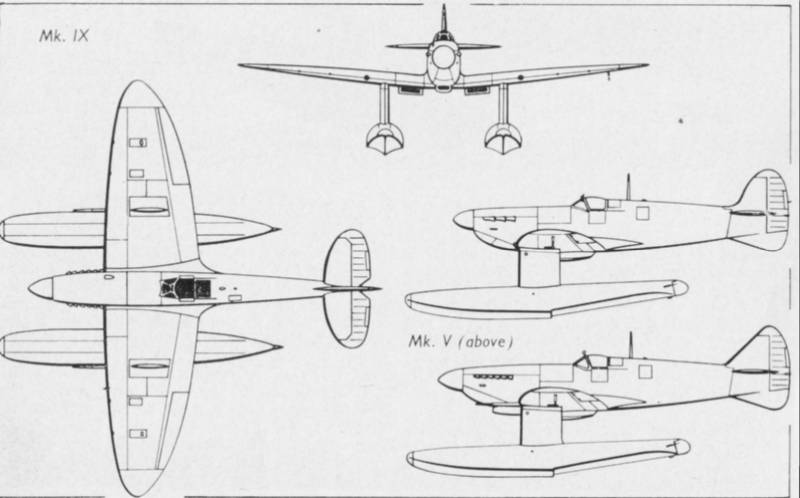

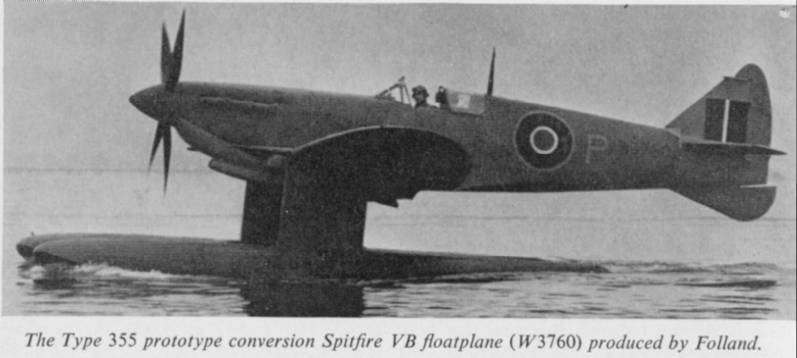

If RN surface ships are repeatedly being found without air cover, then an immediate remedy like one-way, high-performance Hurricat fighters used on CAM ships should have been placed on-board; two cruisers each with 4 x Hurricats would mean 8 fighters; 3 cruisers 12 and so on. The next thing that could have been done is to apply a single float under centerline with two small outrigger floats at the wings so the seaplane fighters could have been recovered and re-used. Apparently the twin-float system was tried on Hurricane and a Spitfire; the latter still had high speed. Twin-floats offer twice the water resistance upon landing and can result in a crash; the single float cuts through the water better but takes greater pilot skill.

Hawker Hurricane Seaplane Fighter

http://airfixtributeforum.myfastforum.org/ftopic9488-0-asc-20.php

http://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=84&t=14002

Supermarine Spitfire Seaplane Fighter

The invasion of Norway by German forces on 9 April, 1940, brought to the fore Britain's urgent need for a seaplane fighter capable of operating from Norwegian fjords or other sheltered strips of water, and as a panic measure, both Vickers-Armstrongs and Hawkers were asked to produce float-equipped versions of their respective fighters, the Spitfire and the Hurricane. In the event, the Norwegian campaign terminated before either float fighter was flown, but while further work on the Hurricane seaplane was abandoned, development of the Spitfire seaplane continued, resulting in the fastest float seaplanes of the Second World War.

The original Spitfire seaplane project, the Type 243, known less officially as the "Narvik Nightmare", was begun in April 1940, and owing to the exigencies of the time was an adaptation of a standard Spitfire Mk 11 to take a pair of single-step Alclad Blackburn Shark floats similar to those employed by the Roc seaplane. These floats were obviously too large and too heavy for the Spitfire, and there were some doubts that the bracing structure between the floats and wings would possess sufficient strength. It was perhaps fortunate, therefore, that the conversion was never completed, the onset of the "Battle of Britain" necessitated the reconversion of the aircraft as a standard Spitfire Mk II.

In May 1940, a conversion of the Spitfire with floats of Supermarine design, the Type 344, was already proposed, but it was not until September 1941 that the scheme was revived with the Type 355, a conversion of a Sptifire Mk VB (W3760) to take Supermarine-designed floats. The actual conversion was undertaken by Folland Aircraft, and apart from the attachments of the floats by cantilever pylons to the inboard wing sections, the aircraft had the carburetor air intake extended forward to avoid the entry of water spray, and the vertical tail surfaces were increased in area by the forward extension of the fin and the provision of an additional ventral fin.

Initial trials revealed that the water handling of the Spitfire seaplane and its behaviour during take-off and alighting were very good, and at normal taxiing speeds in winds up to 20 mph only a fine spray was thrown into the airscrew arc. In the air, the fighter handled well, except for an appreciable change in elevator trim during diving and a substantial yaw which developed when the pilot throttled back, and the addition of the floats had very little effect on maneuverability which was of an extremely high order.

As a result of the success of initial trials, Folland Aircraft were instructed to manufacture twelve sets of floats and conversion kits, and two further Spitfire Mk VBs were converted (EP751 and EP754). However, a change in policy after the completion of the first two "production" conversions resulted in the discontinuation of further work on the Spitfire Mk VB seaplane in favour of a conversion of the more powerful Spitfire Mk IX. Eight sets of floats already manufactured were modified for installation on the later Spitfire variant, and a Spitfire Mk IX (MJ892) was converted as a prototype, the modifications being substantially the same as those made to the earlier conversions.

The Spitfire Mk IX seaplane displayed an outstanding performance and would have undoubtedly have proved its worth in the Pacific, but official policy dictated concentration on carrier-borne rather than float-equipped fighters, and the whole scheme was abandoned early in 1944.

[EDITOR: the Pacific? Why not on CAM ships in the Atlantic?]

Spitfire Mk VB seaplane fighter conversion

Type: Single-seat Twin-float Seaplane Fighter

Power Plant: One 1,470 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin 45 twelve-cylinder Vee liquid-cooled engine

Armament: Two 20 mm Hispano cannon with 120 rpg and four 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns with 350 rpg

Performance: Maximum speed, 251 mph at sea level, 267 mph at 5,000 ft, 306 mph at 15,500 ft, 324 mph at 19,500 ft; economical cruising speed, 180 mph at 6,000 ft, 200 mph at 20,000 ft; initial climb rate, 2,240 ft/min, maximum climb rate, 2,450 ft/min at 15,500 ft; time to 5,000 ft, 2.2 min, to 10,000 ft 4.4 min, to 25,000 ft, 12.3 min; service ceiling, 33,400 ft; range, 336 mls at 200 mph at 20,000 ft

Weights: Empty, 6,014 lb; normal loaded, 7,580 lb

Dimensions: Span, 36 ft 10 in; length, 35 ft 4 in; height, 13 ft 10 in; wing area, 242 sq ft

Spitfire Mk IX seaplane fighter conversion

Type: Single-seat twin-float Seaplane Fighter

Power Plant: One 1,720 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin 66 twelve-cylinder Vee liquid-cooled engine

Armament: Two 20 mm Hispano cannon with 120 rpg and four 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns with 350 rpg

Performance: Maximum speed, 316 mph at sea level, 353 mph at 9,000 ft, 377 mph at 19,700 ft; economical cruising speed, 225 mph at 10,000 ft; initial climb rate, 3,700 ft/min; maximum climb rate, 3,800 ft/min at 6,500 ft; service ceiling, 36,000 ft; range 460 mls at 225 mph at 10,000 ft (with 50 Imp gal drop tank), 770 mls

Weights: Empty, 6,500 lb; normal loaded, 8,200 lb; maximum, 8,610 lb

The text and photos were taken from Warplanes of the Second World War: Vol 6 Seaplanes.

Dimensions: Span, 36 ft 10 in; length, 35 ft 6 in; height (tail down on land), 10 ft 0 in; wing arera 242 sq ft

www.youtube.com/watch?v=dtzWHDUtTJc

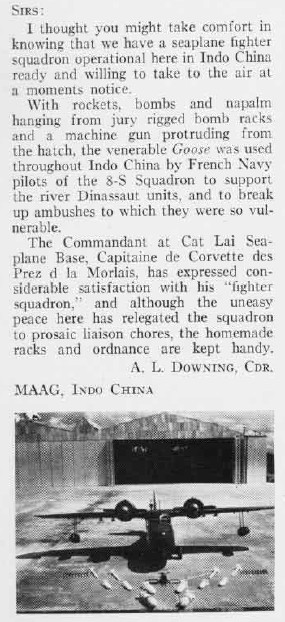

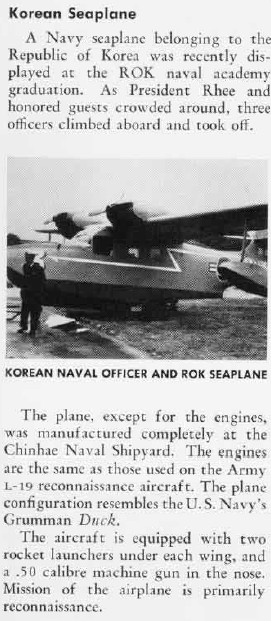

www.youtube.com/watch?v=dtzWHDUtTJc