Do you SEE Pirates? Sea Pirates: Scourge of the Seas

By Mike Sparks

Most people have a romantic notion that Sea Pirates ended with the age of sailing ships and have an infatuation for those days as the popularity of the Walt Disney-theme park inspired "Pirates of the Caribbean" movies series proves. Aside from Johnny Depp's swashbuckling and Keira Knightly's cleavage, most people cannot SEE the truth that piracy has continued into our age of the propeller-driven steel ships; its just not a fun-filled story. The pirates of old were not nice guys--either as you probably guessed--but the idea of rebelling against society's norms and living free has its biker club appeal.

What is important here is one technique of the sea pirates: the wearing of FALSE FLAGS in order to deceive intended victims. (Stop looking at Keira Knightly!)

The USS Big Horn: Not an unarmed Oil Tanker!

Its of extreme importance--not just because of the temporary tactical advantage of getting "the drop" on the local victims, its the GEOSTRATEGIC importance that if the deception holds, an entirely WRONG GROUP GETS THE BLAME FOR THE ATTACK

. In my earlier web page, on Axis & Allied Special Operations Aviation, I point out how a ship like the HMS Campbeltown in WW2 was made to look like an enemy ship and was filled with high explosives to ram the dry docks at St. Nazaire to prevent German Navy surface ships from commerce raiding.www.combatreform.org/axisandalliedspecialoperationsaviation.htm

The False Flag appearance of the Campbeltown was worn in order to get close enough to ram and not be blown out of the water. Aircraft are even more fragile than ships, and in war have been painted to look like enemy aircraft to attack enemy forces and insert/extract agents, a legacy that was continued on to the September 11, 2001 attacks where a surplus U.S. Navy (USN) A-3D Skywarrior was painted to look like a Boeing 757 in American Airlines Flight 77 colors and markings to con the American public into thinking it was hijacked (skyjacked) by Islamic ragheads to enrage them into a never-ending war against sub-national groups feeding the budgets of the evil James Bonds and the unemployed John Waynes. The main Illuminati objective was to take-over Afghanistan and Iraq for oil/drug profits.

www.combatreform.org/seeisNOTbelieving.htm

SEEing things for what they really are is critical in conflict.

For example, the vast majority of the murders committed in the United States are attempted to be hidden by the perpetrators such that little or no evidence remains. Thus, the apologists for the 9/11 perps who whine about "a lack of evidence" are naive at best and traitors at worst for they ignore the most basic reality of human crimes: that those evil enough to do them are also evil enough to hide them. The "lack of evidence" is for 19 ragheads with box-cutter knives skyjacking and ramming anything that day as put out by the AmeroNazi traitor, former Solicitor General of the U.S., Ted Olson while working for W. Bush.

www.combatreform.org/tedandbarbaradid911.htm

What we are going to examine on this web page is how Sea Piracy using False Flags has continued from the age of sail to the present day showing that the 9/11 attack pedigree is WESTERN--not Eastern and Islamic. The HMS Campbeltown hoisting the white ensign of the Royal Navy before ramming the docks is all a part of the Pirate ship fun & games western military men play.

Nation State Wars: Commerce Raiding--and Defense--by False Flag

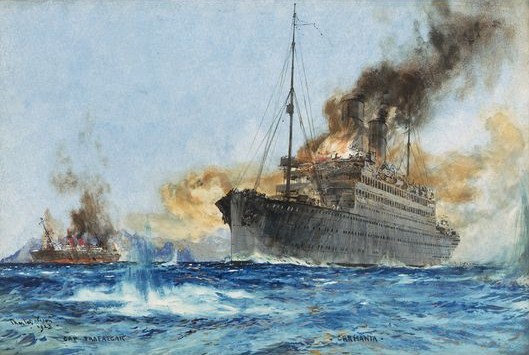

You are not seeing things! It's an armed British cargo ship sinking a German armed passenger ship in WW1! Hardly TV's "Love Boat" or teary-eyed "Titanic", isn't it?

American Naval theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan is the culprit behind the narcissistic egomania that inflicts itself within the USN; he wants to sink the enemy's fleet--not baby-sit civilians in cargo ships. He is not alone as many weak ego military men want to self-validate by dueling mirror images of themselves. The problem is that societies--the people who actually create goods and services that need the John Waynes to protect (think his excellent 1965 movie In Harm's Way) may require commerce by sea to exist or nothing follows. England's survival depended on those raggedy merchant ships--and from an offensive perspective so did Japan. Yet, the egomaniac USN wanting to sink others in capital ships was not interested in placing merchant ships into convoys to protect them and we almost lost two world wars because of it. However, we might succeed and lose the next won, we Americans are persistently stupid. We forget that it was the French navy's blockage that enabled us to win our independence from England in 1783. It was the Russian Navy's help blockading supplies to the southern Confederate states that enabled us to win our Civil war and keep American united. Mahan must have skipped over those sections of history when writing his feel-good, naval narcissistic crap. Fortunately, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was the same way and ignored emphasizing its submarines to interdict our logistics by sinking our cargo ships, instead hunting for our fleet for their fleet to sink it--in climactic battle reliving 1904's Tshushima.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tsushima

So while the navies park their fleets in port waiting for the "big one" or sail circles in the middle of the blue water ocean, the real battle for survival takes place depending on whether the commerce ships can get through or not. Sea mines can all but shut down a sea-dependent nation and the RN forced Germany to look landward for resources. To get through the RN blockade, the Germans cleverly created armed merchant ships that could change their appearances instantly to sink cargo ships. They also created fast heavy cruisers AKA "pocket battleships" that could sprint through gaps in the blockade to prey upon the cargo ships England depended on.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merchant_raider

Merchant raider

Merchant raiders are

ships which disguise themselves as non-combatant merchant vessels, whilst actually being armed and intending to attack enemy commerce. Germany used several merchant raiders early in World War I, and again early in World War II. The most famous captain of a German merchant raider, Felix von Luckner, used a sailing ship SMS Seeadler for his voyage during World War I.Germany sent out two waves of six surface raiders each during

World War II. Most of these vessels were in the 8-10,000 ton range. Many of these vessels had originally been refrigerator ships, used to transport fresh food from the tropics. These vessels were faster than regular merchant vessels-important for a warship. They were armed with 6 x 15 cm (5.9 inch) naval gun, some smaller calibre guns, mines and torpedoes. Some of them were fitted for minelaying. Some of the captains were very creative about disguising their vessels to masquerade as allied or neutral merchants. Italy used four "Ramb" class ships as auxiliary cruisers in World War II.These commerce raiders were unarmoured because their purpose was to attack merchantmen, not to engage naval units in open combat. Also it would be difficult to fit armour to a civilian vessel. Eventually most were sunk or transferred to other duties.

British

Armed Merchant Cruisers were generally adapted from passenger liners, and were larger than the German vessels.During

World War I, the Royal Navy deployed Q-ships to engage German U-boats. Although Q-ships were warships pretending to be merchant ships, their mission of destroying enemy warships was significantly different to the raider objective of disrupting enemy supplies.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_auxiliary_cruiser_Atlantis

German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis

|

Atlantis |

|

|

Career (Germany) |

|

|

Name: |

Goldenfels |

|

Operator: |

Hansa Line |

|

Builder: |

|

|

Launched: |

1937 |

|

Homeport: |

|

|

Fate: |

Requisitioned by Kriegsmarine, 1939 |

|

Career |

|

|

Operator: |

|

|

Builder: |

|

|

Yard number: |

2 |

|

Commissioned: |

30 November 1939 |

|

Renamed: |

Atlantis , 1939 |

|

Reclassified: |

Auxiliary cruiser, 1939 |

|

Nickname: |

HSK-2 |

|

Fate: |

Sunk, 23 November 1941, in the South Atlantic |

|

General characteristics [1] |

|

|

Type: |

|

|

Tonnage: |

7,862 gross register tons (GRT) |

|

Displacement: |

17,600 t (17,300 long tons) |

|

Length: |

155 m (509 ft) |

|

Beam: |

18.7 m (61 ft) |

|

Draught: |

8.7 m (29 ft) |

|

Installed power: |

7,600 hp (5,700 kW) |

|

Propulsion: |

2 × 6-cylinder diesel engines1 × shaft |

|

Speed: |

17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) |

|

Range: |

60,000 nmi (110,000 km; 69,000 mi) at 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h) |

|

Endurance: |

250 days |

|

Complement: |

349-351 |

|

Armament: |

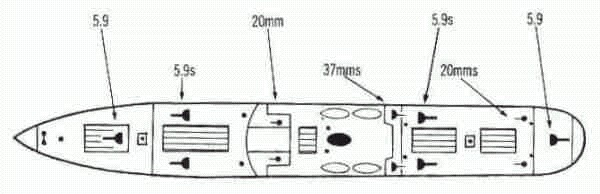

6 × 150 mm (5.9 in) guns 2 × twin 20 mm cannons 4 × 533 mm (21 in) torpedo tubes 92 × mines |

|

Aircraft carried: |

2 × Heinkel He 114B |

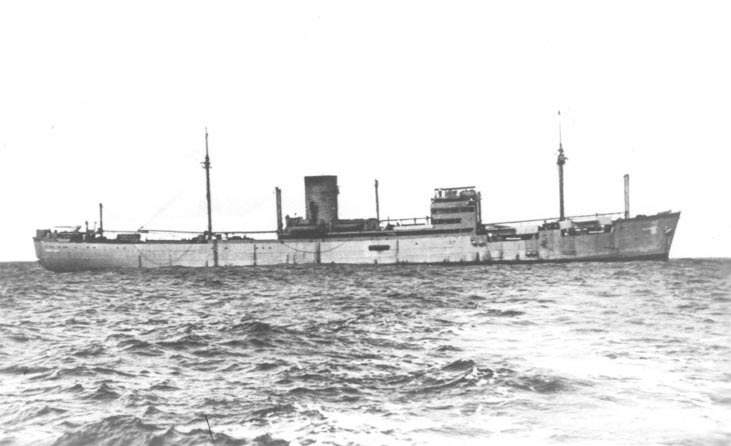

The German

She was commanded by

Kapitän zur See Bernhard Rogge, who received the Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.Commerce raiders do not seek to engage warships, but rather to attack enemy merchant shipping; the measures of success are tonnage destroyed (or captured), and time spent at large. Atlantis was second only to

Pinguin in tonnage destroyed, and had the longest raiding career of any German commerce raider in either world war.She had a significant effect on the war in the Far East due to capture of highly significant secret documents from

SS Automedon.Early history

Formerly a

freighter named Goldenfels, she was built by Bremer Vulkan in 1937, and was owned and operated by the Hansa Line, Bremen. In late 1939, she was requisitioned by the Kriegsmarine and converted to a warship by DeSchiMAG, Bremen, and was commissioned as the commerce raider Atlantis in November 1939.[2]:6-7Design

Atlantis was 155 m (509 ft) long and displaced 17,600

t (17,300 long tons). She had a single funnel amidships. She had a crew of 349 (21 officers and 328 enlisted sailors) and a Scottish terrier, "Ferry", as a mascot. The cruiser carried a dummy funnel, variable-height masts, and was well supplied with paint, canvas, and materials for further altering her appearance, including costumes for the crew, and flags. Atlantis was capable of being modified to 26 different silhouettes.Weapons and aircraft

The ship carried one or two

Heinkel He-114B seaplanes, four waterline torpedo tubes, and a 92-mine compartment. The ship was also equipped with six 150 mm (5.9 in) guns, one 75 mm (3.0 in) gun on the bow, two twin-37 mm anti-aircraft guns and four 20 mm automatic cannons; all of these were hidden, mostly behind pivotable false deck or side structures. A phony crane and deckhouse on the aft section hid two of the 150 mm (5.9 in) guns; the other four guns were concealed via flaps in the side [3][4]:46 that were lowered when action was needed.Engines

Atlantis had two 6-cylinder

diesel engines, which powered a single propeller. Top speed was 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph).Service history

Atlantis

, Krim and Kasii MaruIn 1939, Atlantis was part of the

Hansa Line under the name Goldenfels. In 1939, she became the command of Kapitän Bernhard Rogge. Commissioned in mid-December, she was the first of nine or ten merchant ships armed by the Third Reich for the purposes of seeking out and engaging enemy cargo vessels. Atlantis was delayed by ice until 31 March 1940, when the former battleship Hessen was sent to act as an icebreaker clearing the way for Atlantis, Orion, and Widder.Atlantis headed past the

North Sea minefields, between Norway and Britain, across the Arctic Circle, and after passing between Iceland and Greenland, headed south. By this time, Atlantis was pretending to be a Soviet vessel named Krim by flying the Soviet naval ensign, displaying a hammer and sickle on the bridge, and having Russian and English warnings on the stern, "Keep clear of propellers". The Soviet Union was neutral at the time.After crossing the equator, on 24-25 April, she "became" the

Japanese vessel Kasii Maru. The ship now displayed a large K upon a red-topped funnel, identification of the Kokusai Line. She also had rising sun symbols on the gun flaps and Japanese characters (copied from a magazine) on the aft hull.City of Exeter

On 2 May, she met the British passenger liner

SS City of Exeter. Rogge, unwilling to cause non-combatant casualties, declined to attack. Once the ships had parted, Exeter's Master radioed his suspicions about the "Japanese" ship to the Royal Navy.[5]The Scientist

On 3 May, Atlantis met a British freighter, The Scientist, which was carrying ore and jute. The Germans raised their battle ensign and displayed signal pennants stating, "Stop or I fire! Don't use your radio!" The 75 mm (3.0 in) gun fired a warning shot. The British immediately began transmitting their alarm signal, "QQQ...QQQ...Unidentified merchantman has ordered me to stop," and the Germans began transmitting so as to jam the signals.

The Scientist turned to flee, and on the second salvo from Atlantis, flames exploded from the ship, followed by a cloud of dust and then white steam from the boilers. A British sailor was killed and the remaining 77 were taken as prisoners of war. After failing to sink the ship with demolition charges, guns and a torpedo were used to finish off The Scientist.

Cape Agulhas

Continuing to sail south, Atlantis passed the Cape of Good Hope, reaching Cape Agulhas on 10 May. Here, she set up a minefield with 92 horned contact naval mines, in a way which suggested that a U-boat had laid them. The minefield was successful, but the deception was foiled and the ship's presence revealed by a German propaganda broadcast boasting that "a minefield, sown by a German raider" had sunk no fewer than eight merchant ships, three more were overdue, three minesweepers were involved, and the Royal Navy was not capable of finding "a solitary raider" operating in "its own back yard". Furthermore a British signal was sent from Ceylon on 20 May and intercepted by Germany, based on the report from City of Exeter, warning shipping of a German raider disguised as a Japanese ship[5].

Atlantis headed into the Indian Ocean disguised as Dutch vessel MV Abbekerk. She received a broadcast-which happened to be incorrect-reporting that Abbekerk had been sunk, but retained that identity rather than repainting, as there were several similar Dutch vessels[5].

Tirranna

, City of Baghdad, and the KemmendineOn 10 June, Atlantis stopped the Norwegian motor ship Tirranna with 30 salvos of fire after a three-hour chase.[2]:79-80 Five members of Tirranna's crew were killed and others wounded. Filled with supplies for Australian troops in the Middle East, Tirranna was captured and sent to France.

On 11 July, the liner City of Baghdad was fired upon at a range of 1.2 km (0.75 mi). A boarding party discovered a copy of Broadcasting for Allied Merchant Ships, which contained communications codes. City of Baghdad, like Atlantis, was a former Hansa Liner, having been captured by the British during World War I. A copy of the report sent by City of Exeter was found, describing Atlantis in minute detail and including a photograph of the similar Freienfels, confirming that the "Japanese" identity had not been believed. Rogge had his ship's profile altered, adding two new masts[5].

At 10:09 on 13 July, Atlantis opened fire on a cargo ship, Kemmendine, which was heading for Burma. Filled with whisky, Kemmendine was quickly ablaze and a boarding crew returned with only two stuffed animals. Lifeboats were taken aboard which carried women and children.

Talleyrand

and King CityIn August, Atlantis sank Talleyrand, the sister ship of Tirranna. Then she encountered King City, carrying coal, which was mistaken for a British Q-Ship due to its erratic maneuvering, which was caused by mechanical difficulties. Three shells destroyed the bridge, killing four merchant cadets and a cabin boy. Another sailor died on the operating table aboard Atlantis.

Athelking

, Benarty, Commissaire Ramel, Durmitor, Teddy, and Ole JacobIn September Atlantis sank Athelking, Benarty, and Commissaire Ramel. All of these were sunk only after supplies, documents, and POWs were taken. In October, the Yugoslavian steamboat Durmitor was taken and was loaded with documents and 260 POWs, and dispatched to Italian-controlled Mogadishu. Lacking sufficient fuel, the steamer resorted to sails and, after a "hellish" voyage, made landfall in Somaliland on November 22, five weeks after departure. In the second week of November, Teddy and Ole Jacob were seized.

Automedon

and her secret cargoMain article: SS Automedon

At about 07:00 on 11 November, Atlantis encountered the Blue Funnel Line cargo ship Automedon about 250 mi (400 km) northwest of Sumatra. At 08:20, Atlantis fired a warning shot across Automedon's bow, and her radio operator at once began transmitting a distress call of "RRR - Automedon - 0416N" ("RRR" meant "under attack by armed raider").[citation needed]

At a range of around 2,000 yds. (1,800 m) Atlantis shelled Automedon, ceasing fire after three minutes during which she had destroyed her bridge, accommodation, and lifeboats. Six crew members were killed and 12 injured.

The Germans boarded the stricken ship and broke into the strong room, where they found 15 bags of Top Secret mail for the British Far East Command, including a large quantity of decoding tables, fleet orders, gunnery instructions, and naval intelligence reports. After wasting an hour breaking open the ship's safe, to discover only "a few shillings in cash", a search of the Automedon's chart room found a small weighted green bag marked "Highly Confidential" containing the Chief of Staff's report to the Commander in Chief Far East, Robert Brooke Popham. The bag was supposed to be thrown overboard if there was risk of loss, but the personnel responsible for this had been killed or incapacitated. The report contained the latest assessment of the Japanese Empire's military strength in the Far East, along with details of Royal Air Force units, naval strength, and notes on Singapore's defences [4]:117. It painted a gloomy picture of British land and naval capabilities in the Far East, and declared that Britain was too weak to risk war with Japan.

Automedon was sunk at 15:07. Rogge soon realised the importance of the intelligence material he had captured and quickly transferred the documents onto the recently acquired prize vessel Ole Jacob, ordering Lieutenant Commander Paul Kamenz and six of his crew to take charge of the vessel. After an uneventful voyage they arrived in Kobe, Japan on 4 December 1940.

The mail reached the German embassy in Tokyo on 5 December, and was then hand-carried to Berlin via the Trans-Siberian railway. A copy was given to the Japanese where it provided valuable intelligence prior to their commencing hostilities against the Western Powers. Rogge was rewarded for this with an ornate katana Samurai sword; the only other Germans so honored were Hermann Goering and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

After reading the captured Chief of Staff's report, on 7 January 1941 Japanese Admiral Yamamoto wrote to the Naval Minister asking whether, if Japan knocked out America, the remaining British and Dutch forces would be suitably weakened for the Japanese to deliver a deathblow: the Automedon intelligence on the weakness of the British Empire is credibly linked with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the attack leading to the fall of Singapore[6][7].

At Kerguelen and Africa

During the Christmas period, Atlantis was at Kerguelen Island, in the Indian Ocean. There they did maintenance and replenished their water supplies. The crew suffered its first fatality when a sailor fell while painting the funnel. He was buried in what is sometimes referred to as "the southernmost of all German war graves" [4]:134.

In late January 1941, off the eastern coast of Africa, Atlantis sank the British ship Mandasor and captured Speybank. Then, on 2 February, the Norwegian tanker Ketty Brøvig was relieved of her fuel. The fuel was used not only for the German raider, but also to refuel the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer and, on 29 March the Italian submarine Perla. Perla was making its way from the port of Massawa in Italian East Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope, to Bordeaux in France.

Zamzam

By April, Atlantis had returned to the Atlantic where, on April 17, Rogge, mistaking the Egyptian liner Zamzam for a British liner being used as a troop carrier or Q-ship, as she was in fact the former Bibby Liner Leicestershire, opened fire at 8.4 km (5.2 mi). The second salvo hit and the wireless room was destroyed. 202 people were captured, including missionaries, ambulance drivers, Fortune magazine editor Charles J.V. Murphy, and Life magazine photographer David E. Scherman. The Germans allowed Scherman to take photographs, and although his film was seized when they returned to Europe aboard a German blockade runner, he did manage to smuggle four rolls back to New York. It is generally believed that his photos later helped the British identify and destroy Atlantis.[citation needed] Murphy's account of the incident, as well as photos by Scherman, were in the June 23 issue of Life.

Post-Bismarck

After the German battleship Bismarck was sunk, the North Atlantic was swarming with British warships. As a result, Rogge decided to abandon the original plan to return to Germany, and instead returned to the Pacific.[2]:185-7 En route, Atlantis encountered and sank the British ships Rabaul, Trafalgar, Tottenham, and Balzac. On 10 September, east of New Zealand, Atlantis captured the Norwegian motor vessel Silvaplana.

Atlantis then patrolled the South Pacific,[8] initially in French Polynesia between the Tubuai Islands and Tuamotu Archipelago. Without the knowledge of French authorities, the Germans landed on Vanavana Island and traded with the inhabitants. They then hunted Allied shipping in the area between Pitcairn and uninhabited Henderson islands, making a landing on Henderson Island. The seaplane from Atlantis made several fruitless reconnaissance flights. Atlantis headed back to the Atlantic on 19 October, and rounded Cape Horn ten days later.

U-68

, U-126, and HMS DevonshireOn October 18, Rogge was ordered to rendezvous with the submarine U-68 800 km (500 mi) south of St. Helena and refuel her, then he was to refuel U-126 at a location north of Ascension Island. They met with U-68 on 13 November. On 21 or 22 November, Atlantis rendezvoused with U-126 and Kapitänleutnant Ernst Bauer came aboard to take a bath. Around this time Kapitänleutnant Ulrich Mohr, Rogge's adjutant, is reported to have woken from a recurring nightmare about a three-funneled British cruiser.[2]:208

Sunk and sunk again

Early on the morning of 22 November Atlantis was intercepted by British heavy cruiser HMS Devonshire of the 3-funnel County class. U-126 dived, leaving her captain behind. There is dispute as to whether Rogge ordered his ship to stop engines. [4]:190 At 08:40, Atlantis transmitted a raider report posing as the Dutch ship Polyphemus, but by 09:34 Devonshire had received confirmation that this was false[9]. From 14-15 km (8.7-9.3 mi) away, outside the range of Atlantis's 150 mm (5.9 in) guns, she opened fire.

After 20-30 seconds, salvos of 8 in (200 mm) shells began to reach Atlantis; the second and third salvos hit the ship. Seven sailors were killed as the crew abandoned ship; Rogge was the last off. Ammunition exploded and the bow rose, then the ship sank.

Devonshire left the area and the U-126 resurfaced and picked up 300 Germans and a wounded American prisoner, whom it began carrying or towing to Brazil (1,500 km (930 mi) west). Two days later the German refueling ship Python arrived and took on the sailors. On 1 December, while Python was refueling two submarines, the third of the British cruisers seeking the raiders, HMS Dorsetshire, appeared. The U-boats dived immediately, and Python's crew scuttled her; Dorsetshire departed and it was left to the U-boats to recover the crew. Eventually various German and Italian submarines took Rogge's crew back to Germany.

Raiding career

- Ships sunk or captured by Atlantis

Further reading

- Duffy, James P. Hitler's Secret Pirate Fleet: The Deadliest Ships of World War II Praeger Trade, 2001, ISBN 0275966852.

- Hoyt, Edwin Palmer Raider 16 World Publishing, 1970.

- Mohr, Ulrich And A. V. Sellwood Ship 16: The Story of the Secret German Raider Atlantis John Day, New York, 1956.

- Muggenthaler, August Karl German Raiders of World War II Prentice-Hall, 1977, ISBN 0133540278.

- Rogge, Bernhard The German Raider Atlantis Ballantine, 1956.

- Schmalenbach, Paul German Raiders: A History of Auxiliary Cruisers of the German Navy, 1895-1945 Naval Institute Press, 1979, ISBN 0870218247.

- Slavick, Joseph P. The Cruise of the German Raider Atlantis Naval Institute Press, 2003, ISBN 1557505373.

- Swanson, S. Hjalmar (editor) Zamzam: The Story of a Strange Missionary Odyssey 1941.

- Woodward, David The Secret Raiders;: The Story of the German Armed Merchant Raiders in the Second World War W.W. Norton, 1955.

www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2-1Epi-c5-WH2-1Epi-j.html

These surface raiders could have created a decisive synergism working in concert with their submarines (U-boats) and long-range maritime patrol bomber Fw-200 Condors--had the British let them. Fortunately for us, we fought back in those days by actual adaptation to the problem--instead of making excuses for what our bureaucracies want to do to milk the problem and feed greed and egos. So if the Germans wanted to sink cargo ships with disguised cargo ships, we would hunt them down with our own disguised cargo ships and overt cruisers. If the German submarines wanted to surface and sink ships on the cheap with deck guns, Q-ships were waiting for them--cargo ships filled with floatation material that couldn't be sunk even by expensive torpedoes. The Q-ships were very effective in WW1 but the German U-boat commanders were wise to them come WW2. If the German surface cruisers and battleships wanted to sortie out to sink cargo ships, the Royal Navy would sink them first by aircraft bombing, torpedoes and smash their repair docks even by ramming a ship of their own made to look like one of theirs.

What is interesting is that the Germans while not being trapped by Allied Q-Ships adopted the technique for themselves to use against British commerce since they didn't have their own commerce to defend from Allied submarines. One of the German False Flag Raiders, the Atlantis captured secret British military papers revealing their weakened state of defense in the Pacific that emboldened the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor and expand throughout the Pacific. Was this a military blunder or a deliberate bait to get them to attack? What's fascinating is that once the intelligence was collected it was transported across RUSSIA to Berlin because at that time the Soviet Union was Hitler's ally. It's a good thing Hitler and Stalin became enemies or we'd all be speaking German today.

Commander Ian Fleming of NID17 was the second-in-command of British Naval Intelligence in WW2 and knew all about false flag operations, planning his own Operation RUTHLESS in 1940 to steal German naval code machines by way of a captured German He-111 bomber. After the war, in his James Bond 007 novel, Thunderball he has the villain Largo operate from a ship the Disco Volante that its actually a hydrofoil complete with scout seaplane and underwater diving capabilities like the German Q-ships were in WW2.

Commander Ian Fleming, RNVR.

WHO writes later in his 007 James Bond novel Thunderball about planes being hijacked...and False Flag attacks in Moonraker...art imitates life...

Details to be covered in my new book coming out in spring 2011!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_pocket_battleship_Admiral_Scheer

Following Hitler's anger at the alleged failings of the Kriegsmarine, its commander-in-chief, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder was replaced by Admiral Karl Dönitz, and the German surface fleet rarely left port thereafter.

Admiral Donitz: Maybe Not So Brilliant After All?

Another turning point was when after all the RN smothering took effect, Hitler was pissed off and fired Admiral Raeder and replaced him with U-boat-only Donitz. Any chance of surface/sub-surface synergism was lost--which was fortunate for us. By 1941 the German surface ship threat was gone by RN smothering and Hitler's bad decisions. One could say that Germany was wasting money on surface ships and could build 10 U-boats for every cruiser etc. however, by limiting the threat to one dimension, it enabled the allies to focus all their resources to defeat it--instead of 3 dimensions. If Germany was to gain by concentrating on U-boats it didn't pay-off in the form of high-speed, Type XXI true submarines until too late. The pugnacious military mind wants to duel--with someone---and doesn't care about the point of the war or how to win it. So Admiral Donitz is sending out his Wolfpacks to sink convoys and building concrete pens for them to return to and avoid Allied bombing when he should have been laying SEAMINES to seal off England and starve her into submission. Laying a sea mine is not very ego gratifying to say the least, but it works. Even the USN and USSAF got around to laying sea mines by war's end to seal off Japan.

The point here is that the USMIL ignorant of the threat of high explosives (HE) both unguided and as Precision-Guided Munitions (PGMs)

www.combatreform.org/highexplosives.htm

does not want to smother it let alone use it to their own maximum advantage unless in an ego-gratifying way: TOP GUN narcissist in a fighter-bomber from a bloated expensive supercarrier drops a PGM etc. Thus, minesweeping is as low a priority in the Navy as it is in the Army on land. Both services are dominated by gunslingers who want to duel mirror images of themselves. What we need is an unsinkable ship full of floatation material that can gobble up seamines and pre-detonate them to clear sea lanes for both cargo container ships and oil tankers--as well as our warships. Without them, we are sunk, literally and figuratively.

www.combatreform.org/armysappersforward

Thus, in the next major nation-state war (NSW) the U.S. Navy could be defeated by seamines sealing off a Taiwan even before it can arrive. When it does, it'll be in too few vulnerable thinly-armored surface ships that cannot put enough aircraft into the skies to stop PGMs from raining on them and sinking them--just like the RN did to the German surface fleet in WW2. Game over before we even get a chance to play John Wayne. Our supercarrier and amphibious ship imbalanced, USN needs to drastically reform itself in light of the PGM threat that is growing and stop trying to relive WW2 badly which could prove fatal. In WW2, we had 124 carriers to darken the skies with airplanes to prevent enemy attacks; today we can only put less than a dozen ships to sea with a pathetic array of aircraft.

www.combatreform.org/USNAVYINDANGER/index.htm

Sub-National Conflicts: The Sea Pirates Have Returned

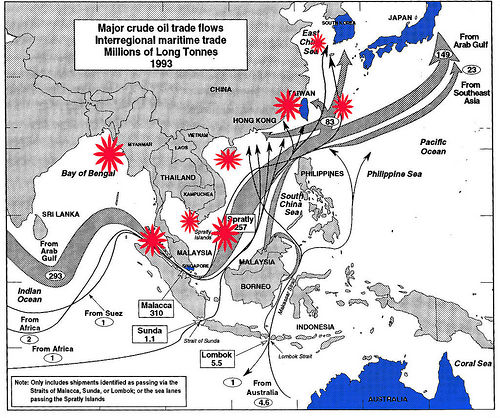

Today's many sea commerce chokepoints

The Mahan-deluded USN has traditionally not been interested in doing its job. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King had to be ORDERED by President of the United States (POTUS) Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) to form convoys and protect our cargo ships--AFTER hundreds were sunk and thousands of people had died. Military egotists have no conception that wars can be lost if their society's ability to create war material is taken from them--as General William Sherman proved by marching across the south to end the U.S. Civil War in 1864-1865.

General Sherman: "War is Hell"--that's why he chose to end it quickly by "Marching to the Sea"

Modern Sea Pirates: the U.S. Military Response Sucks (To Put It Mildly)

Since the U.S. Navy and marines are off in their own fantasy world of reliving WW2 badly or goofing off chasing wine, women and song, it should come as no surprise when actual Sea Pirates capture an American cargo ship they are caught with their pants down. We are not talking last year's incident off Somalia, but the 1975 debacle when the SS Mayaguez was taken by Kymer Rouge gunmen.

1975: the Mayaguez Incident

So let's get this straight.

The United States has just ended fighting the Vietnam war, and when the Mayaguez is taken we have U.S. marines already in a guard duty garrison mentality where issuing live ammunition is some sort of divine experience. Their sleeves are rolled up. Their equipment is not camouflaged. They don't have any observation/attack reconnaissance planes nearby so a guy with a 35mm SLR camera has to snap pictures of Koh Tang island from a passenger plane window to determine where they are going to air assault onto open beaches without first sending in any recon pathfinders. Don't laugh--the USMC would do the same thing again in 1995 in Bosnia but got away with it. This time they paid dearly.

www.combatreform.org/pathfind.htm

So no one is looking through the jungle foilage with forward looking infared (FLIR) or ground penetrating radar because in the USMIL, the Battle Against the Earth (TBATE) is ignored--how do you think we failed to close the Ho Chi Minh's supply trails in the decade previously? The Luddite marines don't need no stinkin' technology.

www.combatreform.org/TRANSFORMATIONUNDERFIRE/index.htm

So when the USAF's HH/CH-53 Super Jolly Green Giant helicopters land the dumb marines, the enemy dug-in and camouflaged blasts them out of the sky with automatic weapons kinetic energy (KE) bullets and rocket-propelled grenades (HE). A huge clusterfuck ensues and the marines are nearly annihilated before the USAF and USN pulls them out. 10 marines were left behind (not the Kirk Cameron movie series) alive and were tortured and murdered in the rush to escape.

www.combatreform.org/kohtang.htm

Destroyed USAF helicopters filled with dead marines and airmen on Koh Tang island beach

So much for "first to fight" and "never leave a man behind" and what not. If you are a narcissistic egomaniac you can do none of these things when it requires HUMILITY and TANGIBLE PREPARATION to be ready with little or no notice. It'd be nice to report that things have gotten better in the USMIL bureaucracy, but bureaucracy does what bureaucracy wants. Bureaucracy is not a profession.

2009: Somali Pirates Try to Seize the Container Ship Maersk Alabama: Crew Ready, USMIL Not Ready

Real Somali Pirates: Anyone look like Johnny Depp or Keira Knightly?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piracy_in_Somalia

Piracy off the Somali coast has been a threat to international shipping since the second phase of the Somali Civil War in the early 21 century. Since 2005, many international organizations, including the International Maritime Organization and the World Food Programme, have expressed concern over the rise in acts of piracy.[2] Piracy has contributed to an increase in shipping costs and impeded the delivery of food aid shipments. Ninety percent of the World Food Programme's shipments arrive by sea, and ships have required a military escort.[3] According to the Kenyan foreign minister, Somali pirates have received over U.S. $150 million in ransom during the 12 months prior to November 2008.

Precise data on the current economic situation in Somalia is scarce but with an estimated per capita GDP of $600 per year, it remains one of the world's poorest countries. Millions of Somalis depend on food aid and in 2008, according to the World Bank, as much as 73% of the population lived on a daily income below $2. These factors and the lucrative success of many hijacking operations have drawn a number of young men toward gangs of pirates, whose wealth and strength often make them part of the local social and economic elite. Abdi Farah Juha who lives in Garoowe (100 miles from the sea) told the BBC, "They have money; they have power and they are getting stronger by the day. [...] They wed the most beautiful girls; they are building big houses; they have new cars; new guns."

Container Ship Maersk Alabama

On April 7, 2009 the U.S. Maritime Administration, following

NATO advisories, released a Somalia Gulf of Aden advisory to Mariners recommending ships to stay at least 600nmi off the coast of Somalia. With these advisories well in effect, on April 8, 2009, four Somali pirates boarded the Maersk Alabama when it was located 240 nautical miles (440 km; 280 mi) southeast of the Somalia port city of Eyl. With a crew of 20, the ship was en route to Mombasa, Kenya. Maersk Line Limited, (part of the Moller-Maersk Group, the largest shipping company in the world) is one of the United States Department of Defense's primary shipping contractors, although the vessel was not under military contract at the time. The ship was carrying 17,000 metric tons of cargo, of which 5,000 metric tons were relief supplies bound for Somalia, Uganda, and Kenya.

The 28 foot lifeboat where

Captain Richard Phillips and the four Somali pirates were held up as seen from a U.S. Navy Scan Eagle UAV.According to Chief Engineer Mike Perry, the engineers sank the pirate speedboat shortly after the boarding by continuously swinging the rudder of the Maersk Alabama thus scuttling the smaller boat. As the pirates were boarding the ship, the crew members locked themselves in the engine room while the captain and two other crewmembers remained on the bridge.[

citation needed] The engineers then took away control of the ship from down below, rendering the bridge controls useless.[citation needed] The pirates were thus unable to control the ship. The crew later used "brute force" to overpower one of the pirates, Abduhl Wal-i-Musi and free one of the hostages, ATM Reza. Frustrated, the pirates decided to leave the ship, and took Phillips with them to a lifeboat as their bargaining chip. The crew attempted to exchange this captured pirate, whom they had kept tied up for twelve hours, for Captain Phillips. The captured pirate was released but the pirates refused to release Phillips. After running out of fuel in the ship's man overboard boat, they transferred and left in the ship's covered lifeboat, taking Phillips with them. The lifeboat carried ten days of food rations, water and basic survival supplies.On April 8, the destroyer

USS Bainbridge (DDG-96) and the frigate USS Halyburton (FFG-40) were dispatched to the Gulf of Aden in response to a hostage situation, and reached Maersk Alabama early on April 9. Maersk Alabama then departed from the area with an armed escort, towards its original destination in Mombasa, Kenya, with the vessel's Chief Mate, Shane Murphy in charge. On Saturday, April 11, Maersk Alabama arrived in the port of Mombasa, Kenya, still under U.S. military escort, where C/M Murphy was relieved by Captain Larry Aasheim, who had previously been captain of the Maersk Alabama until Richard Phillips relieved him eight days prior to the pirate attack. An 18-man marine security team was on board. The FBI secured the ship as a crime scene.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maersk_Alabama_hijacking

On April 10, 2009, Phillips attempted to escape from the lifeboat but was recaptured after the captors fired shots. The pirates then threw a phone-and a two-way radio dropped to them by the U.S. Navy-into the ocean, fearing the Americans were somehow using the equipment to give instructions to the captain.

The WIKI account soft-pedals the fact that Captain Philips of the Maersk Alabama jumped from the covered lifeboat with the 3 gunmen as the USN destroyer USS Bainbridge shadowing it did nothing!

How low the USN has degenerated! This isn't Steve McQueen in the Sand Pebbles which shows the can-do gunboat Navy of long ago. The USN ship today is a HORIZONTAL OFFICE BUILDING that floats filled with bureaucrats ordering around office workers in a shirt-sleeve environment. A giant file cabinet at sea. Its not a WAR ship filled with warriors who can board ships and shoot guns with accuracy to handle pirates on-the-spot. Thus, when the captain makes a break for freedom by jumping from the lifeboat, he gets ZERO SUPPORT from the Sailors watching from the rear!

Disgusting.

How hard is it to blow away everything and everyone in the lifeboat as soon as the hostage has left it?

Does it take a Navy SEAL sniper to do this?

No, "experts" have to be flown in from COMNAVSPECWARUGETHEPICTURE to take-out the bad guys, who fortunately didn't execute the captain after his unsuccessful self-rescue attempt.

2010: the Q-Ships Return

Finally, someone figures out maybe its time to ambush the ambushers. The armed merchant ship. What an original concept!

http://militarytimes.com/blogs/scoopdeck/2009/06/18/the-return-of-the-mystery-ships/

The return of the 'Mystery Ships'

The Q-Ship Big Horn, which you probably thought was just an innocent fleet oiler, actually was modified to hunt and kill German U-Boats. // Naval History and Heritage Command

By way of New Wars comes

a captivating item about a Malaysian container ship that has been converted into a naval auxiliary for escort work off the lawless coast of Somalia - just like the famous Q-Ships fielded by the U.S. and Royal Navies to escort convoys back in World Wars I and II.Just as when Navy trade show speakers finish their remarks and then greet audience members afterward - but one of those audience members turns out to be a Navy Times reporter - so too did the Q-Ships pretend to be merchant vessels to entice submarine attacks, then open up with their guns and depth charges.

Malaysia's conversion of the container ship

Bunga Mas Lima is apparently a response to the hijacking last year of two Malaysian ships, the Bunga Melati Dua and Bunga Melati 5.

The Malaysian navy's new "Q-Ship," Bunga Mas Lima // Deltamarin

The problem, as New Wars' Mike Burleson points out, is that despite the schoolboy-adventure romance surrounding Q-Ships, they didn't have that successful a track record against German U-Boats. We'll be watching to see how Malaysia's does.

Burleson is INCORRECT. Q-Ships/Armed Merchant Ships were highly successful in WW1 against German submarines and in WW2 against merchant ships.

Even the American Q-ships in WW2 had some success; the USS Big Horn thwarted several U-boat attacks and appears to have sunk at least one enemy submarine with its own anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weaponry. American Q-ships were defective in they were not made sink-proof by adequate watertight compartments filled with floatation materials. Read the detailed account below.

www.history.navy.mil/docs/wwii/Q-ships.htm

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY -- NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER

805 KIDDER BREESE SE -- WASHINGTON NAVY YARD

WASHINGTON DC 20374-5060

Q-Ships (Anti-submarine vessels disguised as merchant vessels)

Related Resources:

List of Q-Ships with links to their historiesAdapted from

: "Eastern Sea Frontier War Diary," October 1943, ch.2, "Queen Ships." pp.9-34. Modern Military Branch, National Archives and Records Administration, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740.Prologue: End of the Q-Ship Program

Origins of Q-Ships in World War I

Q-Ships in World War II

Sinking of USS Atik (AK-101) by German submarine U-123

Cruises of USS Asterion (AK-100)

Cruises of USS Eagle (AM-132)/USS Captor (PYC-40)

Cruises of USS Big Horn (AO-45)

USS Irene Forsyte (IX-93)

Selected Bibliography for Further Information

Prologue: End of the Q-Ship Program

In the early morning hours of October 4, 1943, a dispatch from the three-masted schooner Irene Forsyte [IX-93] reported that she was hove to in approximately 38-00 N, 66-00 W; that many leaks had developed during the course of a heavy storms that her pumps were just able to keep ahead of water. The message further stated that the condition might become serious if the heavy weather continued; for that reason, permission was requested to proceed to Bermuda for repairs. First action was taken by Cinclant [Commander-in-Chief, US Atlantic Fleet], who immediately ordered two tugs to proceed to the scene and render assistance. Later in the day, however, the Irene Forsyte reported that no assistance was needed, that she was proceeding to Bermuda, The tugs were recalled.

On October 14, 1943; Cominch [Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet] directed the Commander Eastern Sea Frontier to decommission the Irene Forsyte upon her return from Bermuda; to take other steps which would lead to the conclusion of all antisubmarine patrols by Eastern Sea Frontier vessels disguised as merchant vessels. This decision had been brought to a head by the failure of Eastern Sea Frontier "Queen ships" to accomplish their intended missions. The conclusion of "Queen ship" missions in the waters of the Eastern Sea Frontier offers an appropriate occasion for reviewing the essential details as to their various developments and operations from the beginning of the war to the decommissioning of Irene Forsyte (IX-93).

Origins of Q-Ships in World War I

There is nothing new or secret about the general principle of Q-ship operations. When the U-boats [German submarines] were at their worst in World War I, the British Admiralty approved and authorized the conversion of merchant vessels to heavily armed raiders which would have her guns disguised or concealed in such a way that the merchant vessels might serve as decoys which would encourage U-boats to attack them. Then, provided the disguised merchant vessel had been given sufficient buoyancy, so that one or two torpedoes would be unable to sink her, the disguise was to be thrown off, the guns brought to bear, the U-boat sunk. The entire effectiveness of the enterprise depended on the successful use of surprise, and once the U-boats were aware of the ruse, the chances of success were so greatly reduced that only a few ingenious Commanding Officers were able to conduct Q-ship campaigns throughout the remainder of World War I with any distinction.

Q-Ships in World War II

In World War II, the sudden appearance of U-boats in Atlantic coastal waters led to considerations of all possible means for meeting the emergency. Sinkings began on January 14th, and shipping losses mounted rapidly. On January 20, 1942, Cominch sent for information to Commander Eastern Sea Frontier a coded dispatch which was paraphrased as follows:

"Immediate consideration is requested as to the manning and fitting-out of Queen repeat Queen ships to be operated as an antisubmarine measure. This has been passed by hand to OpNav [Office of the Chief of Naval Operations] for action."

In answer, Commander Eastern Sea Frontier wrote a lengthy letter under the date of January 29th, pointing out that the most prevalent method of U-boat attack had been night attacks on the surface from close range; that U-boats were concentrating on tankers. For this reason it was pointed out that a tanker would best answer the purpose of inviting attack after having been fitted out as a Q-ship. It was further suggested that another type of Q-ship might be a vessel "of such a relatively insignificant appearance that upon sighting it a submarine would not submerge." This implied that a small schooner might serve the purpose.

This letter containing details as to procedure, was forwarded by Cominch to the Chief of Naval Operations on February 15, 1942, and CESF [Commander Easter Sea Frontier] was informed that the proposals had been "noted with interest" and were "under consideration." Five days later, on February 20, 1942, the Chief of Naval Operations informed Commander Eastern Sea Frontier that his proposals had been approved, that hereafter the matter would be known as "Project LQ"; that all communications on the matter would be made by word of mouth, insofar as practicable; that a responsible officer would be placed in charge of the work; that on completion, "Project LQ" would be assigned to the force of the Commander Eastern Sea Frontier.

Prior to the inception of "Project LQ," Cominch had arranged for the selection of three other vessels considered suitable for the intended purpose: a Boston trawler and two small cargo vessels of the three-island type. The beam trawler, diesel powered, had formerly operated with the fishing fleet out of Boston under the name, MS Wave. She was originally acquired. for conversion to an auxiliary minesweeper by the Commandant First Naval District. In fact, she was commissioned at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on March 5, 1942, as USS Eagle (AM-132). Her length was 133 feet, beam 26 feet, maximum speed, 10 knots. Her armament included one four-inch-fifty gun, two .50 calibre machine guns, 4 depth charge throwers, 2 Lewis .30 caliber machine guns, 5 sawed-off shotguns, 5 Colt .45 automatics and 25 hand grenades. She was also equipped with WEA echo ranging and listening equipment. Her complement was 5 officers and 42 enlisted men.

The two cargo vessels had been built at Newport News, Virginia, in 1912 and were of standard type: 3,209 gross tons, 318 feet in length, 46 foot beam. In commercial circles they were known as SS Carolyn and SS Evelyn; were owned and operated by the A. H. Bull Steamship Company in New York City. For their new assignment, they were taken over for naval use by Mr. Huntington Morse and Mr. S. H. Heimbold of the U. S. Maritime Commission. During their conversion in the Navy Yard at Portsmouth, N. H., each vessel was armed with four 4-inch-fifty caliber guns, four .50 caliber machine guns, six single depth charge throwers and a miscellaneous collection of small arms similar to those aboard USS Eagle.

The complement of each ship was six officers and 135 enlisted men. Although these three vessels were regularly commissioned by the Commandant Navy Yard, Portsmouth, N. H., by direction of the Chief of Naval Operations - SS Carolyn as USS Atik (AP-100) and SS Evelyn as USS Asterion (AP-101) - and so recorded in the Log of that Yard, the commissionings were not made a matter of record in the Navy Department. The status of USS Eagle (AM-132) remained unchanged in the department's records, since she had originally been acquired for conversion to AM and had been so designated in the records of the Department. Thereafter, all pertinent information containing these vessels was kept in a secret file in the custody of the Vice Chief of Naval Operations.

Some complicated problems of protocol were solved while the ships were still being converted. In order to preserve the highest possible degree of secrecy in operating the merchantmen and the beam trawler, $500,000 was allotted from an Emergency Fund so that expenditures would not be directly accountable through the General Accounting Office and the Treasury. On February 19, 1942, the Chief of Naval Operations (Admiral H. S. Stark, USN) opened a joint account in the Riggs National Bank, Washington, D. C. in the name of F. J. Horne and/or W. S. Farber, and deposited the sun of $500,000, with the understanding that the Chief of Naval Operations might at times request transfer of funds from this account to other names. He then requested immediate transfer of the following sums to the following accounts:

|

Eagle Fishing Company, L. F. Rogers, Master |

$50,000 |

|

Asterion Shipping Company, K. M. Beyer, Treasurer |

$100,000 |

|

Atik Shipping Company, E. T. Joyce, Treasurer |

$100,000 |

Such an arrangement permitted the purchase of supplies for the individual ships involved without the customary naval requisition procedure.

After many other minor details had been ironed out, the next step was the arrangement for operational directives which might be foolproof. On March 11th, the Commanding Officers of USS Eagle, USS Asterion and USS Atik (Lieut. Comdr. L. F. Rogers, USNR, Lieut. Comdr. G. W. Legwen, USN, and Lieut. Comdr. Harry L. Hicks, USN, respectively) were given personal and written instructions at Headquarters, Commander Eastern Sea Frontier. They received a preliminary Operation Order to cover a brief period of shakedown, which would start about Match 24, 1942. Since they would be departing from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, they were to report to Commander Submarine Division 101 when ready for sea; then proceed independently on widely separated courses for shakedown in areas where enemy activity had not been reported. USS Atik and USS Asterion were to navigate so that one should be approximately 480 miles to the southward of the other after five days at sea. These ships were to leave the Navy Yard, Portsmouth, in such manner that they would appear to all observers as armed vessels regularly commissioned in the Navy; then at the first opportunity, guns and depth charge throwers were to be concealed, identifying numbers removed from the bows, commission pennants hauled down, and other steps taken to have USS Atik and USS Asterion present the appearance of merchantmen; USS Eagle the appearance of a beam trawler fishing out of Boston. From the viewpoint of security, the most serious difficulty in carrying out this plan was that there had been scores of civilian workers in the Portsmouth shipyard which had known about the conversion peculiarities of structure on these vessels, and the subject of these "Q-ships" was subsequently reported (by one wife of an officer aboard USS Atik) to have been common knowledge in several Portsmouth boarding houses.

On completing shakedown, these ships were to report to Commander Eastern Sea Frontier by dispatch, and at that time the second Operation Plan would be made effective by dispatch from Commander Eastern Sea Frontier. This second Operation Plan, also issued under date of March 11, 1942, applied only to the Atik and the Asterion. Therein they were directed to operate independently in the waters off the United States Atlantic Coast, roughly 200 miles off the coast. Special instructions pointed out that the identity of these vessels must remain secret until action was joined; that action should be joined only when en enemy submarine was at sufficiently close quarters to insure its destruction by superior gunfire, followed by depth charge attacks if it succeeded in submerging before destruction. It was further pointed out that enemy submarines had been attacking during darkness; that they were rarely seen until after the vessel was struck by a torpedo. As for possible circumstances under which friendly ships or aircraft might challenge the Atik and the Asterion, they were instructed to use as identification their former names and calls, which would indicate that they were SS Carolyn and SS Evelyn, owned by the A. H. Bull Steamship Company; that if enemy ships should challenge, reply should be made in accordance with International Procedure, using the calls and identifications as follows:

Atik: SS Vill Franca, Portuguese Registry, Call CSBT

Asterion: SS Generalife, Spanish Registry, Call EAOQ

As for eventual return to port, instructions were given that notice should be sent to Commander Eastern Sea Frontier, who would inform Mr. Huntington Morse or Mr. S. F. Helmbold of the Maritime Commission at Washington, that one of these men should inform the senior Maritime Commission representative at the port of entry; that a Maritime Commission representative at the port would receive lists of requirements from the Commanding Officer after arrival and would designate an agent to furnish them; that the Commanding Officer should ascertain the total cost and should deliver a check for the amount...for the U. S. Maritime Commission.

From March 11th to March 23, 1942, final arrangements were made for the first sailing of these vessels on shakedown, They sailed at 1300 on March 23rd, and the next day one of the officers in the Navy Department wrote, "It's gone with the wind now and hoping for a windfall."

Sinking of USS Atik (AK-101) by German submarine U-123

Unfortunately, the windfall cane all too soon. Before the shakedown cruise was tour days old, USS Atik (SS Carolyn) was attacked and sunk by a U-boat. All bands were listed as "missing." The details of the battle are so sparse as to make any satisfactory reconstruction impossible. It is known that the Atik had been cruising in the general area about 300 miles east of Norfolk; that the Asterion had been cruising some 240 miles to the south of this area. At 1945 on the night of March 26th, the Duty Officer in the Joint Operations Control Room, ESF [Eastern Sea Frontier], was informed that an SOS [radio distress call] had been picked up from an unidentified ship which had been torpedoed. Nothing further.

At 2053, radio stations at Manasquan, New Jersey, and at Fire Island, New York, intercepted the following distress message from SS Carolyn: "SSS SOS Lat. 36-00 N, Long. 70-00 W, Carolyn burning forward, not bad." Two minutes later, a second distress message from SS Carolyn further amplified: "Torpedo attack, burning forward; require assistance." The position indicated that the attack was taking place some 300 miles east by south from Norfolk, and because such distress messages were regular occurrences at this time - and because all available surface craft were on patrol - the dispatch from SS Carolyn resulted in no immediate action. The Duty Officer in the Control Room had not been informed as to the secret nature of the SS Carolyn, and consequently his only action was to forward the dispatch to Cominch. Several hours later, an officer in the Cominch Operations room phoned the Duty Officer, Eastern Sea Frontier, and asked if the Commander Eastern Sea Frontier or the Chief of Staff had been notified. The answer was that they had not been notified. The Duty Officer was informed that they should be, immediately. Because CESF and his Chief of Staff were both in Norfolk on that particular night, the Duty Officer notified the Operations Officer at his home. Early the next morning, an Army bomber was sent to search the area from which the Carolyn had sent her distress message; the destroyer USS Noa [DD-343] and the tug USS Sagamore [AT-20] were sent to the assistance of the Carolyn. The Army bomber returned without having sighted anything, The tug and the destroyer encountered such heavy weather that the tug was recalled on March 25th; the Noa searched the area until fuel shortage compelled her to return to New York on March 30th. Other flights by Army and Navy planes were unsuccessful until March 30th, when two Army planes and one PBY-5A [four-engine Navy patrol bomber] out of Norfolk reported that they had sighted wreckage roughly ten miles south of the original reported position. The Asterion, which had intercepted the distress messages from the Atik, proceeded directly to the area but was unable to find any trace of her sister vessel. The Norwegian freighter SS Minerva was sighted in the vicinity, southbound for St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. On her arrival there, she was boarded and interrogation revealed that her crew had sighted no wreckage and had picked up no survivors. Twelve days later, Commander Eastern Sea Frontier reported all known details to Cominch on the "suspected sinking of the SS Carolyn," and concluded: ". . . it is believed that there is very little chance that any of her officers and crew will be recovered. It is therefore recommended that it no further information is received by April 27, they be considered lost and that next of kin be notified."

The next piece of information came from Berlin on April 9, 1942, in the form of a broadcast recorded by the Associated Press in New York. It was printed in the New York Times on the following day, April 10, 1942:

"The High Command said today that a Q-boat--a heavily armed ship disguised as an unarmed vessel--was among 13 vessels sunk off the American Atlantic coast and that it was sent to the bottom by a submarine only after a `bitter battle.' (In the last war, Q-boats accounted for many submarines which slipped up on them thinking they were easy prey. When the submarines came into range, false structures on the Q-boats were collapsed, revealing an array of guns.)"

"The Q-boat, the communiqué said, was of 3,000 tons and was sunk by a torpedo after a battle 'fought partly on the surface with artillery and partly beneath the water with bombs and torpedoes.'"

So far as United States Q-ships were concerned in World War II, this was the first and the last action with U-boats which produced any positive results. It appears from this unfortunate beginning that the Germans were well aware of Q-ship possibilities; that the element of surprise which had made this type of vessel effective against submarines in World War I had been so completely lost that the Q-ship had become something of an anachronism. Nevertheless, the plan was continued, and the general details of those later developments deserve a place in the history of the Eastern Sea Frontier.

Cruises of USS Asterion (AK-100)

The first cruise of USS Asterion (alias SS Evelyn) began with the shakedown, and continued until April 18, 1942. The incidents of importance in that cruise were many, and they included several sound contacts with U-boats, the sighting of torpedoed merchant vessels and life boats, the rescue of survivors. Furthermore, several contacts with friendly surface craft and aircraft led to awkward situations which required tact and ingenuity on the part of the Commanding Officer. Nevertheless, the first cruise was concluded without any action against enemy submarines. A copy of the formal report of this first cruise, together with "Recommendations for reduction in merchant ship losses and operation of Q-ships" is included in the Appendix to this month's war diary. It is of interest to note that officers in Headquarters, ESF, were so completely unaware of the nature of this ship's mission that they recorded her various dispatches in the Enemy Action Diary for April 4th, April 10th and April 14th, under her commercial name, SS Evelyn.

The second cruise of USS Asterion began on May 4, 1942, in Accordance with CESF'S Operation Plan 5-42, wherein it was stated that the convoy system would be inaugurated between Key West and Norfolk on May 14-15; that USS Asterion had full discretion as to movements in waters off the Atlantic Coast. It was thus indicated that the best possibilities of success would be for the vessel to proceed as an independently routed merchant ship or as a straggler from a convoy. The cruise was uneventful.

The third cruise of USS Asterion began on June 7, 1942, and because of increased submarine activities in the Gulf of Mexico, the vessel proceeded from New York down the coast, passing through the Straits of Florida on June 11th and past Dry Tortugas on June 14th; thence through Yucatan Channel; then after reversing course proceeded to the Mississippi River Delta, thence on a westerly course toward Galveston. The cruise back over a slightly different course was uneventful, and USS Asterion arrived in New York on July 6, 1942.

The fourth cruise of USS Asterion began on July 20, 1942, en route from New York to Key West, were the vessel anchored on July 27th. On the return leg of the voyage, the vessel cruised northward of the Bahamas and then proceeded to the Windward Passage area; thence to New York, arriving August 18, 1942. The only incident of importance during this cruise was that a sick man was removed from the ship by a tug off Chesapeake Light Buoy vessel on August 15th,

The fifth cruise of USS Asterion began late in August and was similar in plan to that of the fourth cruise. The vessel sailed to Key West, refueled and sailed from there on September 12, 1942, returning to New York, The sixth cruise, equally uneventful, began on November 18, 1942 and again the run was made to Key West in accordance with orders from CESF. While in Key West, on November 30th, arrangements were made and carried out for exercises and operations with a "tame" submarine. On December 2, 1942, USS Asterion got underway for Trinidad, BWI, via Old Bahama Channel, following Trinidad convoy routes, including patrols westward of Aruba, The ship was fueled at NOB Trinidad. Bearing repairs, of serious nature, resulted in the delay of sailing from Trinidad from December 12th until December 26th, when USS Asterion departed Trinidad en route for New York, arriving January 10, 1943.

For the next few months, USS Asterion was given an elaborate overhaul. Inspection after her sixth cruise raised considerable doubt as to her ability to remain afloat if hit by a single torpedo because she had three large holds. A representative of the Navy Yard, New York, conferred with the bureau of Ships, Damage Section, who confirmed the opinion that she could not successfully withstand one torpedo hit, and that such a hit would result not only in her eventual sinking but also in such a quick list that her battery would be ineffective. (Undoubtedly this weakness had been demonstrated several months earlier and was responsible for the rapid sinking of the sister vessel, USS Atik.) A conference was held in the office of the Vice Chief of Naval Operations and it was decided to increase flotation by building five transverse bulkheads. It was estimated that this would take three months and that it would cost about $200,000. The work took much longer and cost much more than had been estimated. Not until September 27th was the overhaul completed--more than eight months after the end of the Asterion's latest cruise. The overhaul had included re-subdivision by longitudinal and athwart ship bulkheads, the filling of her holds with 16,772 empty steel flotation drums. The Supervising Constructor estimated that the vessel could be completely flooded and 25% of the barrels completely crushed before her well decks would be awash. Thus it seemed probable that she had an excellent chance of remaining afloat after a U-boat had made a successful attack on her, As for equipment, she had been strengthened until she carried six K-guns, 48 hedgehog barrels arranged in pairs (24 on each side) to fire a pattern 220 feet in length and 274 feet in width, four 50-caliber machine guns, two 40-millimeter machine guns, and three four-inch guns. Her detection equipment included SMSD [Submarine Detector Ship's Magnet] , SF [Surface Search] radar, Fathometer, Listening Gear of Mark 29, and Low Frequency Direction Finder.

On October 14, 1943, Cominch informed Commander Eastern Sea Frontier that USS Asterion would discontinue her previous duties; that she would be inspected by a Board of Inspection and Survey to determine "suitability for useful service" in some other capacity. USS Asterion was subsequently converted for use as a weather-vessel in the North Atlantic.

Cruises of USS Eagle (AM-132)/USS Captor (PYC-40)

The various cruises of the beam trawler, MS Wave, commissioned USS Eagle (AM-132) were as unproductive in results as were those of USS Asterion. Her first cruise, carried out in accordance with CESF Operation Order 3-42 of March 11, 1942, was intended to permit her to operate independently as a Q-ship in the general vicinity of the beam trawler fishing fleet out of Boston, Massachusetts. It was assumed that the true identity and mission of the vessel would become known to the fishing fleet, but it was intended that this knowledge should not be further disseminated. For this reason, prompt reports were to be made to the Commandant First Naval District for appropriate action of any evidence of disloyalty or "loose talk" in the fishing fleet. But it was found that the original equipment of USS Eagle and her weak armament were unsatisfactory for her purpose. As a result, arrangements were made for a three-week overhaul and conversion before she began her first cruise. From April 24th until May 19, 1942, the vessel underwent this overhaul, and because of the new purpose of the ship, her classification and name were changed at that time from USS Eagle (AM-132) to USS Captor (PYC-40).

A new operation plan, dated May 20, 1942, was drawn up for USS Captor by CESE, with the stipulation that the mission of patrol in the area of Georges Bank would be carried out as originally planned. This first cruise began May 26, 1942, and although no events of importance occurred, USS Captor continued to operate in this area during the next twelve months. when U-boat activities in Frontier waters decreased, the vessel was removed from her secret status and was assigned to the First Naval District as a regular armed patrol craft.

Cruises of USS Big Horn (AO-45)

The most formidable of the Q-ships was the tanker SS Gulf Dawn, selected by Commander Eastern Sea Frontier after Cominch had approved his proposal for using a disguised tanker. Conversion was begun in March 1942 at the Bethlehem 56th Street Brooklyn Yard and was continued at the Navy Yard Boston, where the work was finally completed on July 22, 1942. Equipment included five 4-inch .50 caliber single purpose guns, two .50 caliber machine guns, five "Tommy" guns, five sawed-off shotguns, one Model JK-9 listening equipment. She was commissioned USS Big Horn (AO-45) and the Commanding Officer assigned was Commander J. A. Gainard, formerly master of the SS City of Flint, which became the center of an international incident at the beginning of the war, and was later sunk by a U-boat. USS Big Horn cleared the Boston Navy Yard on July 22, 1942 and after two days spent on the degaussing range and in calibrating compasses and radio direction finders, proceeded to Casco Bay for training under Commander Destroyers, Atlantic Fleet. This training period was followed by a shakedown cruise which was completed on August 26, 1942, at which date USS Big Horn put in again at the Navy Yard, Boston, for further alterations and repairs, At that time, the total complement of the vessel was 13 officers and 157 enlisted men.

The first cruise of USS Big Horn began on September 27, 1942, when the ship proceeded from New York with a New York-Guantanamo Convoy, taking a position which permitted the vessel to act as a straggler. The trip was made to Guantanamo without incident, and thereafter the Big Horn was semi-attached to NOB [Naval Operating Base] Trinidad, with orders to operate from that base over the Bauxite route to and from ports where that commodity was loaded. Many ships in this area had been sunk in recent weeks. Ships proceeding from Trinidad were convoyed to a designated point from which they fanned out to take various routes to their ultimate destination. It was directed that the Big Horn should proceed to that point and drop down on independent routes to and from a Bauxite port.

On October 16, 1942, the Big Horn sailed in convoy "T-19" from Trinidad to the point of separation. That same afternoon, three U-boats attacked the convoy, and at 1520 Queen in 11-00 N, 61-10 W, the British steamer SS Castle Harbor was hit on the starboard side by a torpedo and sank in less than two minutes. At almost the same time the United States steamer Winona, coal laden, was struck forward on the starboard side. Later she limped into Trinidad. Soon afterwards, lookouts on the Big Horn sighted a U-boat moving at periscope depth on the port beam, but in such a position that no action could be taken without damaging the United States troopship Mexico or the Egyptian ship Raz El Farog. At 1627, lookouts on the Big Horn again sighted a periscope and conning tower, on the port side, and her four-inch gun was trained in that direction just as a sub chaser crossed through the line-of-fire and dropped five depth charges. Thereafter, the cruise in these waters was continued without incident for several days and the Big Horn returned to NOB Trinidad about October 29th.

A second cruise in company with a convoy from Trinidad was begun by USS Big Horn on November 1, 1942, to a point nearly due north of Paramaribo, where the vessel left the convoy and proceeded on varying courses without incident until return to Trinidad on November 8, 1942.

On November 10, 1942, USS Big Horn sailed in convoy TAG-20, with the gunboat USS Erie [PG-50], two PC [submarine chaser] boats and a PG [patrol gunboat] acting as escorts. As a result of submarine warnings the convoy course was changed so that the approach to Curacao was made from the south and west. Because of engine difficulties, USS Big Horn dropped out of the convoy at 1530 on November 12, 1942, in company with a Venezuelan tanker, and arrived at a point about one and one-half miles off Wilhemstad harbor, where the Curacao-Aruba subsidiary convoys were joining the main convoy. At 1702, a great volume of smoke was sighted as it rose from the stern of USS Erie, about 1,000 yards on the starboard bow of the Big Horn, in 12-07 N, 68-58 W.

It developed that the Erie had been torpedoed on the starboard side aft. The crew of the Big Horn was called to General Quarters, increased speed to 11 knots and proceeded for the scene of action, but repeated orders from Wilhemstad forced the Big Horn to alter course at 1725 and proceed to Wilhemstad. It was noted that the Erie swung into the wind; that efforts were made without avail to subdue the fire. The gunboat was finally beached, officers and crew abandoning ship.

On November 21, 1942, USS Big Horn proceeded from mooring in Curacao and joined a convoy bound for New York, The convoy proceeded on a course for Guantanamo with a Dutch gunboat and four SC boats as escorts. Other vessels joined convoy at Guantanamo until on leaving that meeting point there were 45 ships and 5 escorts in company. The remainder of the cruise to New York via Caicos Passage was uneventful, and the Big Horn anchored at the Narrows, New York at 2040 on December 1, 1942. During the next few weeks, the Big Horn entered the Todd Shipyard at Hoboken, where mousetrap and hedgehog equipment were installed.

On January 27, 1943, new proposals for antisubmarine operations by the Big Horn were submitted to the Chief of Staff , ESF, by three officers: Lieutenant Commander Farley, USN, (officer in charge of the ESF Q-ship project), Lieutenant Commander R. Parmenter (ASW officer) and Lieutenant Hess (Submarine Tracking Officer). Their proposal began by reviewing the fact that antisubmarine measures within ESF had been so successful that no vessels had been sunk in Frontier waters since July 1942; but that more and more enemy submarines were operating in different areas of the Atlantic. It was therefore proposed that a task unit be formed for hunting U-boats in the central Atlantic; that three PC's [submarine chasers] proceed as escort for USS Big Horn, which would thus act as "bait," as fuel and supply ship, and as support in antisubmarine combat. The proposals were approved by Cominch and by Commander Eastern Sea Frontier. On February 19, 1942, Commander Farley was detached from duty as assistant to the Operations officer, ESF, and was directed to assume command of the newly organized Task Group consisting of the Big Horn and three 173-foot PC vessels: PC-560, PC-617 and PC-618. During the period from March 2nd to March 14th, this Task Group conducted training exercises in the New London area with the U. S. submarine Mingo [SS-261] supplied for the purpose by ComsubLant [Commander, Submarine Force, Atlantic Fleet], During the next two weeks the Task Group made a shakedown cruise.

On April 3, 1943, CESF informed Cinclant that the Big Horn and the three PC's would proceed to sea with convoy UGS-7A on April 13th, and that prior to arrival in the vicinity of the Azores the group would drop astern of the convoy and proceed as straggler-with-escorts, although the escorts would remain far enough astern so that they would not be visible to an enemy submarine sighting the Big Horn. Corroboration of this plan was made by Cominch in a letter to Cinclant dated April 7, 1943. Information as to the plan was then communicated by Cinclant to Commander Task Force 64, who was to act as Escort Commander for Convoy UGS-7A. The Task Group was designated 02.10, although it was understood that routine reports would be made via Cinclant during the time in which the Task Group was operating in Atlantic waters outside the waters of the Eastern Sea Frontier. In the organization of the Atlantic Fleet, this Task Group was designated TG 21.8, operating under ComDesDiv 21 [Commander, Destroyer Division Twenty One], riding the destroyer Livermore [DD-429].

Convoy UGS-7A sailed on the morning of April 14, 1943, and the special Task Group joined up off New York and continued in company until 0800 on April 21, when the Group left the convoy and dropped astern twenty-five miles. The cruise was uneventful during the next two weeks. After several changes of course, USS Big Horn was in 29--00 N, 28--10 W at noon of May 3, 1943. Early that morning, a surfaced vessel had been sighted on the horizon, and PC-618 sent in pursuit. At 1104, PC-618 reported a submarine on the surface, distant about 6 miles. At 1235, the Big Horn got a sound contact and delivered a hedgehog attack just after sighting a periscope on the starboard bow at 1242, followed by a heavy swirl as the U-boat dove. At 1333 a second attack was delivered and the contact was lost. At 1540 the contact was regained at 3700 yards and at 1554, speed 5 knots, the Big Horn delivered a third attack. About five of the hedgehog projectiles exploded after they struck the water, and the Big Horn continued in to drop depth charges. Considerable light oil came to the surface and continued to spread for two hours. At 0103 on May 4th an oil patch was visible over an area of 200 to 300 yards. By daylight that morning, all traces of the oil slick were gone. As none of the vessels in the Group were able to establish contact during the next 44 hours, it was presumed that one submarine had been destroyed; that the other U-boat which had been sighted by the PC-618 had moved cut of the area.