A Beach-Head Too Far?

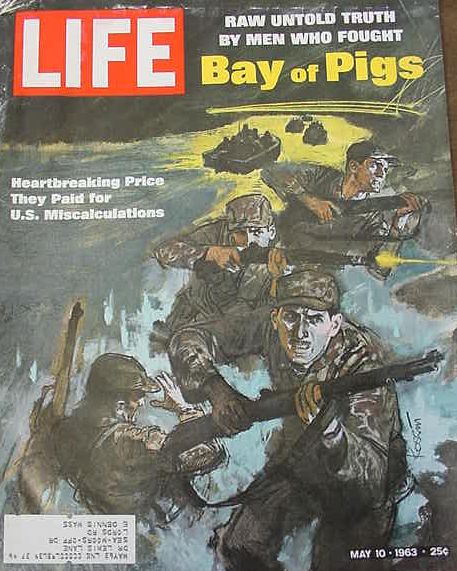

Time to Learn: Lessons from the Failed 1961 Bay of Pigs Amphibious Invasion of Cuba

Introduction to the Geopolitical Situation and CONOPS

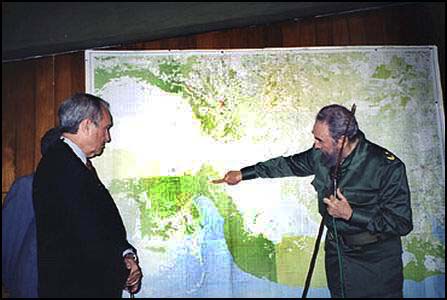

On December 11, 1959, Colonel J.C. King, head of the CIA Western Hemisphere Division, in a secret memorandum to CIA Director Allen Dulles recommended that:

"Thorough consideration be given to the elimination of Fidel Castro. None of those close to Fidel, such as his brother Raul or his companion Che Guevara, have the same mesmeric appeal to the masses. Many informed people believe that the disappearance of Fidel would greatly accelerate the fall of the present Government."

The Caribbean Playground for the CIA

http://alexconstantine.blogspot.com/2008_08_01_archive.html

Thursday, August 28, 2008

Lessons Not Learned at the Bay of Pigs

" ... The Bay of Pigs debacle provided ample warning of the dangers inherent in any interventionist foreign policy. ... "

By Howard Jones

8-18-08

Mr. Jones is the author of the just-published book, The Bay of Pigs (Oxford University Press).

On April 17, 1961, a small band of 1500 Cuban exiles invaded their former homeland at the Bay of Pigs in an attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro. Masterminded by the CIA, the operation hinged on covert action, a pre-emptive strike, and, its greatest novelty, an arrangement with the Mafia to assassinate Castro and set off a popular insurrection. The Kennedy administration had taken a new direction in foreign policy, one that rested on assassination and military force. Indeed, the assassination of Castro was just one part of an executive action program under development inside the CIA that aimed at regime change by simply eliminating troublesome state leaders.

[EDITOR: Assassination and regime change were NOT new CIA M.O.; Allen Dulles under Eisenhower's "New Look" began it to avoid overt U.S. military actions]

The landing, as is well known, was a spectacular failure. Castro not only survived the invasion but outlasted ten presidents despite every effort to force him from office-including at least six attempts at assassination.

The question is, what lessons can be extracted from this fiasco of nearly half a century ago? The short answer is that "regime change" has remained a central part of American foreign policy, meaning that the White House failed to learn anything constructive at the Bay of Pigs.

[EDITOR: the reason is that "regime change" works--to further the profits of American secret elite's business operations just as MG Smedley Butler concluded in the 1930s with his book, War is a Racket. RC didn't happen in the 1961 invasion because of military incompetence which we will go into great detail here to elaborate. The American people must regain control of their own government or else it will continue to be used by the secret elites to do things like "regime change"]

We should start with the CIA. The agency had appeared invincible after its covert triumphs in Iran and Guatemala in the 1950s-which was why the Eisenhower administration authorized it to plan a covert program in Cuba that unexpectedly escalated from guerrilla tactics into an amphibious military operation. At this point, such a highly complex enterprise should have come under the purview of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, but the CIA jealously guarded its mandate, telling the Joint Chiefs that this was "not a military operation" and "You will not become involved in this."

The CIA did not use common sense in partnering with the underworld. Its operatives have often recruited help from unsavory characters-but in this case, they went beyond the pale. "Assassination was intended to reinforce the plan," insisted Richard Bissell, chief architect of the operation. Castro's death would make the invasion "either unnecessary or much easier." Castro had stripped the Mafia of its casinos and other businesses, leaving a thirst for vengeance that provided the CIA with a cover story for plausible deniability-the notion, first stated publicly by agency director Allen Dulles, that one can escape culpability for an act by instituting a loose chain-of-command that leaves no trail of evidence.

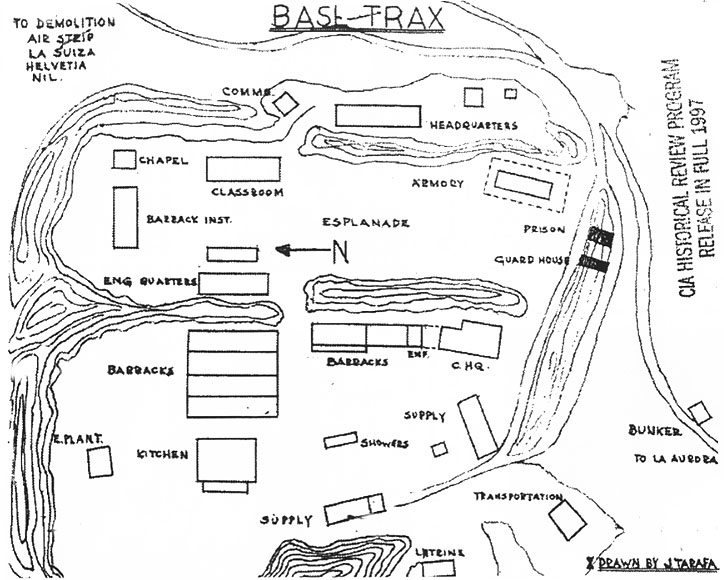

Plausible deniability, however, was an illusion. The CIA assured the White House that it could deny complicity in one of the most open secrets in the annals of secret history. From the beginning came warning signs. The CIA established a training camp in Guatemala for Cuban dissidents run by U.S. Army Special Forces-all known by the Latin public, American newspapers, Castro's spies, and the Soviet news agency Tass. The invasion would take place on April 17, reported the Soviet embassy in Mexico City to Moscow earlier that month.

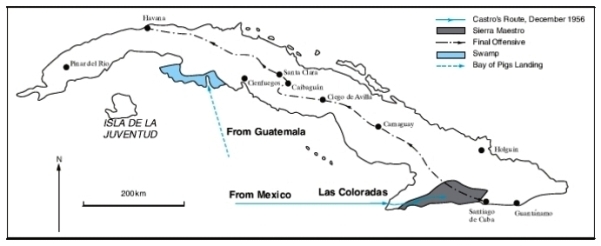

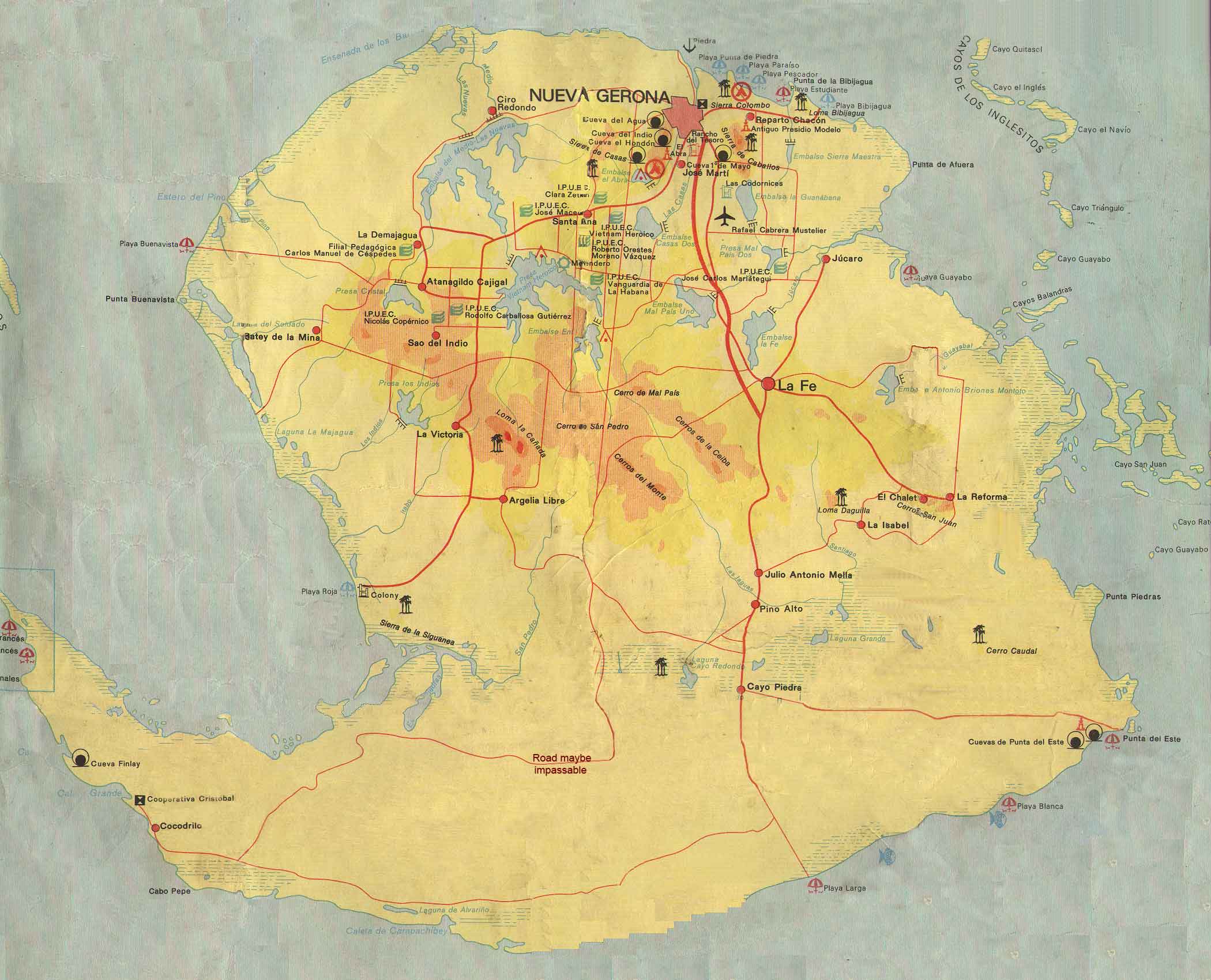

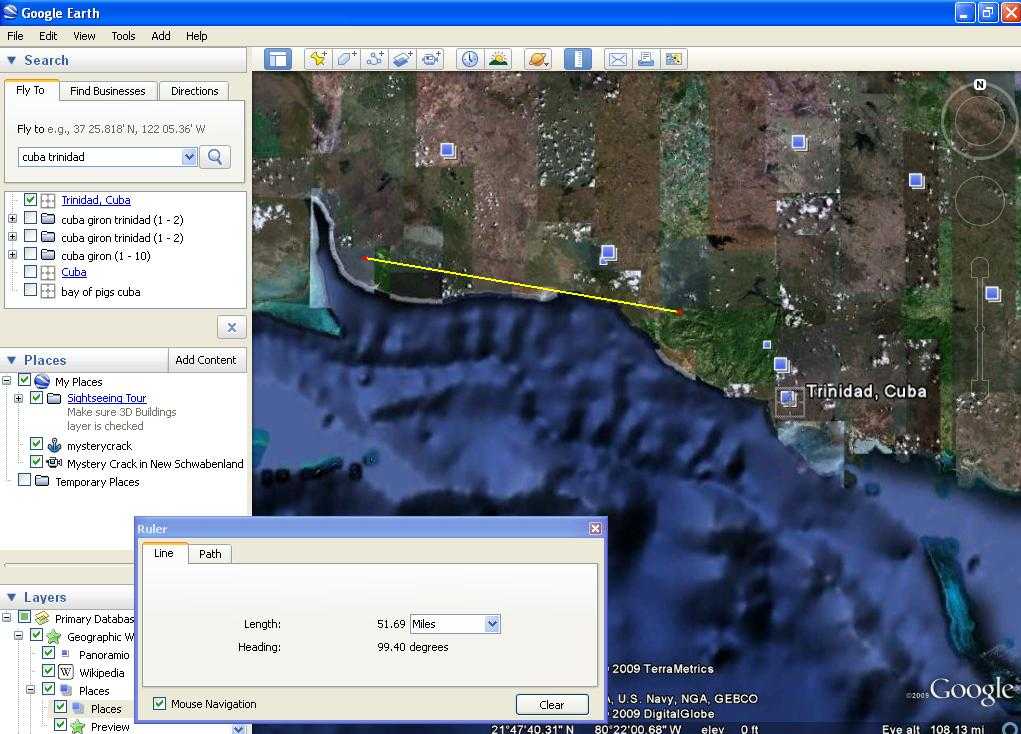

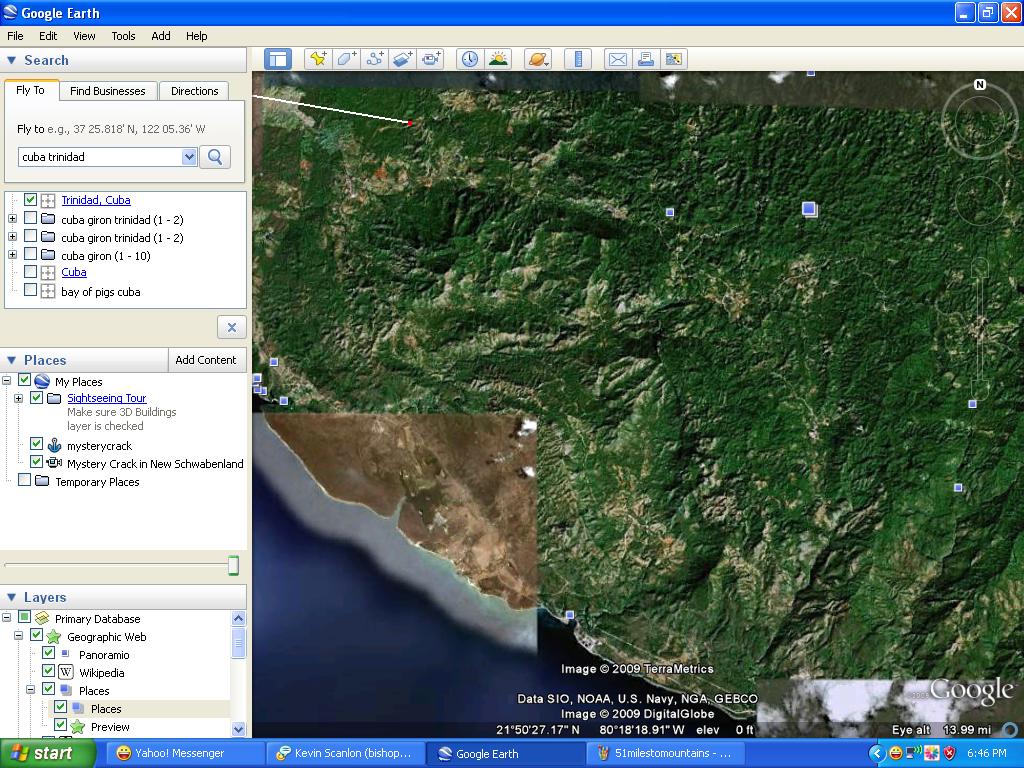

Nevertheless, it was an illusion that Kennedy clung to, particularly because political considerations began to take priority over military strategy. Concern about public exposure led him to reject the original plan for a dawn landing at Trinidad, an anti-Castro town of 18,000 inhabitants that offered potential for a popular uprising, several landing docks, geographical isolation from the regime's forces, and close proximity to the Escambray Mountains, home of a thousand anti-Castro guerrillas and a base for future operations. Kennedy, however, opposed a Normandy-like invasion that exposed U.S. involvement and called for an alternate site allowing a quiet, night-time landing dependent on surprise-which undermined the chances of a popular uprising.

[EDITOR: WTFO? JFK was a PT boat commander. He landed troops on occasion. Trinidad could have been landed on at night. What was going to happen when the sun rose anyway? Ice cream trucks? Here is how Trinidad was to unfold:

utdallas.edu/library/collections/speccoll/Leeker/history/BayOfPigs.pdf

There was still another important change that happened in March 61: The initial plan had been to stage the invasion in the vicinity of Trinidad. "Plan for Landing. The landing plan provided for simultaneous landing at first light on D-Day of two reinforced rifle companies of approximately 200 men each over two beaches southwest of Trinidad and the parachute landing of a company of equal strength immediately north of Trinidad. The remainder of the force was to land over one of the two beaches in successive trips of landing craft. Naval Gunfire. Two LCI each morning mounting eleven 50 caliber machine guns and two 75mm recoilless rifles were to provide naval gunfire support at the beaches. Tactical Air Operations. The plan provided for a maximum effort surprise strike (15 B-26) at dawn of D-1 on all Cuban military airfields followed by repeated strikes at dusk of the same day and at first light of D-Day against any airfields where offensive aircraft were yet operational." 143

However, this "TRINIDAD Plan" was rejected by the Department of State, because to them, it looked like a World War II invasion and would be too obviously attributable to the United States. So on or about 11 March 61, President Kennedy decided that it should not be executed and that possible alternatives should be studied. As according to the new plan any tactical air operations were to be conducted out of an airfield on Cuba, to whom those operations could then be attributed, the Zapata Peninsula of Central Cuba with the new airfield at Playa Girón was chosen, that is the actual Bay of Pigs.

Bissell all too quickly found another landing spot-Zapata, whose focal point for the invasion was much closer to Havana-the Bay of Pigs. But the Zapata peninsula, known as the "Great Swamp of the Caribbean," was sparsely populated, which virtually eliminated an insurrection, and it had no landing docks and was rimmed by shark-infested waters too deep for anchoring in some areas and ribbed with razor-edged coral reefs capable of ripping the bottoms of boats as well as the legs of men. Its beaches wrapped around a million miles of hot tropical wilderness that was overrun with tangled mangrove trees and shrubs, nearly impenetrable thickets, alligators and crocodiles, ferocious pigs, poisonous snakes, voracious insects, and millions of sharp-shelled, toxic red land crabs that in the spring of every year (the time of the invasion) scurried out of the jungle, carpeting the passageways and the beaches in their haste to breed in the sea. Furthermore, the landing site lay eighty miles from the Escambrays, no longer affording a sanctuary because of distance and the deadly swamp lying between. If Bissell was aware of these problems, he did not alert the president to them.

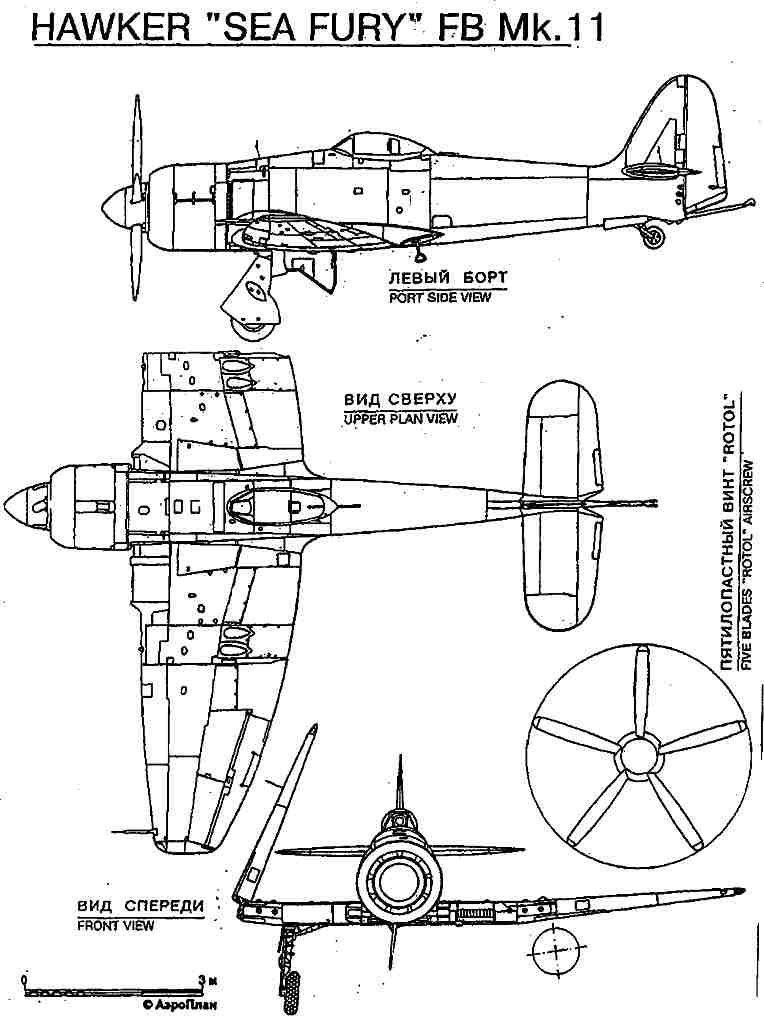

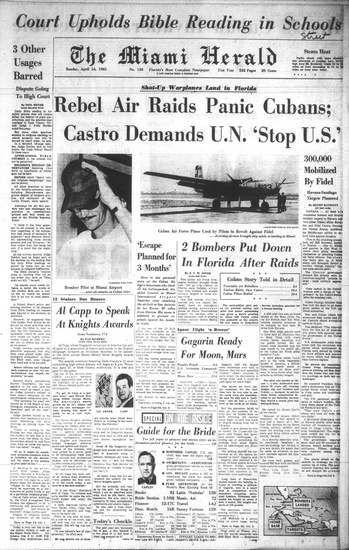

The strategists underestimated the enemy. The CIA and the Joint Chiefs assumed that Castro's forces were lukewarmly loyal and too poorly trained to run the tanks, fight effectively, and pilot his small air force of B-26s, Sea Furies, and T-33 jet trainers. To assure success, the CIA planned two days of pre-invasion strikes by its own B-26s-D-2 and D-1 bombing and strafing that would disable Castro's air and ground forces-followed by D-Day air cover. But Kennedy cut the number of planes in the initial D-2 strikes from sixteen to eight, and then canceled the D-1 operations. Finally, he called off the air cover for D-Day-all to hide the American hand and maintain plausible deniability.

Moreover, the Kennedy administration did not seriously consider the opposition's arguments that even success, which was unlikely, would damage America's international stature. The president dismissed the warnings of Ambassador to India and close confidant John Kenneth Galbraith, Senators J. William Fulbright and George Smathers, Undersecretary of State Chester Bowles, and former Secretary of State Dean Acheson. White House adviser and historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. wrote extensive memos forecasting a public relations catastrophe that would undermine the good will and credibility amassed by the young president in his first months in office. Regardless of the outcome at the Bay of Pigs, the United States would stand as the imperial colossus from the north.

Instead, the White House relied on luck and ingenuity to smooth over the cracks in the plan. Kennedy ignored his own instincts in succumbing to his unusual attraction to guerrilla warfare and the James Bond mystique. Still clinging to the fig leaf of plausible deniability and trusting in the CIA and Pentagon experts as well as in his Midas touch, the president approved the plan. So confident were the planners in a last-minute resort to direct U.S. military action if necessary that they drew up no exit strategy in the event of failure.

In a three-day battle, everything that could go wrong for the Cuban brigade did.

Kennedy's decision to change the landing site from Trinidad to Zapata, and to call off the D-1 and D-Day air strikes doomed the operation from the start. The first move eliminated any chance of a popular uprising; the second left the invasion force with no air cover. Not only did the sharply curtailed D-2 strikes warn Castro of an invasion, but the D-1 and D-day cancellations surrendered the skies to his planes and permitted the more expeditious arrival at the battle scene of his Russian tanks and thousands of militia.

Crucial to the outcome was the absence of a mass uprising. The CIA had not established a network of connections with the local populace; Castro had broken the back of any potential insurrection by clapping thousands of suspects into prison; the invasion had occurred in a place remote and isolated from populated areas; the guerrillas in the mountains were poorly armed and prepared; and the poison plot had failed when the potential assassin feared discovery and sought asylum in the Mexican embassy in Havana.

The most incisive appraisal of the invasion came from Castro, who attributed the brigade's failure to lack of air cover. The rebel planes dropped their airborne battalions too close to the beaches, allowing his tanks and artillery to enter the three causeways leading to the battle sites. The landing spot was superb in military terms, but only if the invaders had closed the causeways and with air protection held the beachhead long enough to build a military and naval base, announce a provisional government, and seek recognition and outside aid. They had a "good plan, poorly executed."

Kennedy's nightmarish experience at the Bay of Pigs certainly helped him stand up to the Soviets in the ensuing Cuban missile crisis; yet one doubts that such a crisis would have occurred without the Bay of Pigs. It is questionable whether Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev would have challenged him at Vienna to pull out of Berlin, but it is inconceivable that he would have risked placing missiles in Cuba had the young president thrown out an invasion plan pockmarked with flaws and aimed at a country posing no threat to U.S. security. Indeed, the Kennedys became so obsessed with Castro that during the missile crisis they spent valuable time planning his elimination out of vengeance for his welcoming the missiles.

But-and here is the critical point-both the president and his brother ignored the lessons left by the Bay of Pigs. Less than two weeks after the invasion and months before the missile crisis, the president gave contingent approval to an air- and marine-force assault on the Havana area followed by the landing of 60,000 American troops. While the Joint Chiefs worked out a detailed plan in the fall of 1961, Kennedy appointed CIA legend Edward Lansdale to head a top-secret program code-named Operation MONGOOSE which, with Robert Kennedy as its real leader, sought to eliminate Castro by any means necessary-including assassination. When MONGOOSE failed and White House attention turned to other trouble spots, the CIA tied the executive action plan to a revived collaboration with the Mafia. In the meantime, both before and after the missile crisis, the agency conspired with a potential assassin to eliminate Castro-Army Major Rolando Cubela, an associate of Castro who had become disenchanted with the political direction of the revolution. On the very day president Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Cubela (code-named Amlash) was meeting in Paris with a CIA operative, making plans for killing Castro either by sniper fire or in the course of a military coup.

President Kennedy soon afterward removed Bissell from his CIA post but praised his "enduring legacy." Bissell had left a lasting mark on foreign policy-but not the type the president had in mind. In a statement that revealed an unintended double meaning if not a healthy dose of naiveté, Kennedy administration insider Richard Goodwin later noted that "Latin America was considered a kind of training ground for Southeast Asia." Indeed, covert tactics aimed at regime change became the norm in Africa and the Middle East as well as in Latin America and Southeast Asia as Washington became enamored of what it could accomplish by clandestine and deniable means.

The Bay of Pigs debacle provided ample warning of the dangers inherent in any interventionist foreign policy. Yet the warning remains unheeded-as shown in Vietnam and Iraq.

http://hnn.us/articles/52561.html

Casualties and losses

FAR

176 killed (Regular Army)

4,000-5,000 killed, missing, or wounded

(Militias and armed civilian fighters)

Assault Brigade 2506

118 killed

1,201 captured

Background

AmeroNazi Richard Nixon as Vice President concocted the whole "Bay of Pigs" thing to regain Mafia night clubs and sugar and tobacco money-makers back into the hands of his Nazi Banker and Mob puppet masters.

historyofcuba.com/history/baypigs/pigs3.htm

Nixon hatches plan

INVASION at Bay of Pigs

"Events are the ephemera of history."

Fernand Braudel

Menu | Intro | The Plan | Invasion | Victory / Defeat | Aftermath | References

The Plan

Vice President Richard Nixon was devoted to the idea of opposing Castro as early as April 1959, when Castro visited the U.S. as a guest of the American Society of Newspaper Editors. "If he's not a communist," said Nixon, "he certainly acts like one." On March 17 1960, President Eisenhower approved a CIA plan titled "A Program of Covert Action against the Castro Regime."

The plan included: 1) the creation of a responsible and unified Cuban opposition to the Castro regime located outside of Cuba, 2) the development of a means for mass communication to the Cuban people as part of a powerful propaganda offensive, 3) the creation and development of a covert intelligence and action organization within Cuba which would respond to the orders and directions of the exile opposition, and 4) the development of a paramilitary force outside of Cuba for future guerrilla action. These goals were to be achieved "in such a manner as to avoid the appearance of U.S. intervention."

Official diplomatic relations were broken on January 1961, nine months after the plan was approved.

The operation came to life when Eisenhower approved an initial budget of $4,400,000. The budget included $950,000 for political action; $1,700,000 for propaganda; $1,500,000 for paramilitary; and $250,000 for intelligence collection. The actual invasion, a year later, would cost U.S. taxpayers over $46 million.

In a meeting at the White House on January 3 1961, described by Richard Bissell, CIA Director of Plans, in his book Memoirs of a Cold Warrior: from Yalta to Bay of Pigs, Eisenhower "seemed to be eager to take forceful action against Castro, and breaking off diplomatic relations appeared to be his best card. He noted that he was prepared to 'move against Castro' before Kennedy's inauguration on the twentieth if a 'really good excuse' was provided by Castro. 'Failing that,' he said, 'perhaps we could think of manufacturing something that would be generally acceptable.' ...This is but another example of his willingness to use covert action-specifically to fabricate events-to achieve his objectives in foreign policy."

By the time Kennedy took office in January 1961, he had already made serious commitments to the Cuban exiles, promising to oppose communism at every opportunity, and supporting the overthrow of Castro. During the campaign, Kennedy had repeatedly accused Eisenhower of not doing enough about Castro.

Eisenhower, Kennedy and other high-ranking U.S. officials continually denied any plans to attack Cuba, but as early as October 31 1960, Cuban Foreign Minister Raúl Roa, in a session at the U.N. General Assembly, was able to provide details on the recruitment and training of the Cuban exiles, whom he referred to as mercenaries and counterrevolutionaries. [The CIA recruits were paid $400 a month to train, with an additional allotment of $175 for their wives and more for their children.]

The original plan called for a daytime landing at Trinidad, a city on the southern coast of Cuba near the Escambray Mountains, but Kennedy thought the plan exposed the role of the United States too openly, and suggested a nighttime landing at Bay of Pigs, which offered a suitable air-strip on the beach from which bombing raids could be operated. Once the bay was secured, the provisional Cuban government-in-arms set up by the CIA would be landed and immediately recognized by the U.S. as the island's legitimate government. This new government would formally request military support and a new "intervention" would take place.

Bissell wrote: "it is hard to believe in retrospect that the president and his advisers felt the plans for a large-scale, complicated military operation that had been ongoing for more than a year could be reworked in four days and still offer a high likelihood of success. It is equally amazing that we in the agency agreed so readily."

A nighttime amphibious landing (which, according to Bissell had only been accomplished successfully once in WWII) diminished the possibility that a mass uprising would be able to join the invading forces. In addition, the new location made it practically impossible to retreat into the Escambray Mountains.

The plan, however, seemed to breed what Néstor T. Carbonell describes in the book, And the Russians Stayed: the Sovietization of Cuba, as infectious optimism. "Castro's fledgling air force was to be destroyed prior to the invasion," he writes. "Enemy troops, trucks, and tanks would not be able to reach the brigade; they would be blasted from the air. To allay any fears of a Castro counteroffensive, the CIA briefer asserted that 'an umbrella' above would at all times guard the entire operation against any Castro fighter planes that might remain operational."

Once Kennedy became aware of the plan, opposition to the invasion was subtly discouraged. Various memos and notes kept from meetings prior to the invasion warned of potential problems and legal ramifications. At a meeting on January 28 the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff spoke strongly against invasion on the grounds that Castro's forces were already too strong. At the same meeting, the Secretary of Defense estimated that all the covert measures planned against Castro, including propaganda, sabotage, political action and the planned invasion, would not produce "the agreed national goal of overthrowing Castro."

On March 29 Senator Fulbright gave Kennedy a memo stating that "to give this activity even covert support is of a piece with the hypocrisy and cynicism for which the United States is constantly denouncing the Soviet Union in the United Nations and elsewhere. This point will not be lost on the rest of the world-nor on our own consciences."

A three-page memo from Under Secretary of State Chester A. Bowles to Secretary of State Dean Rusk on March 31 (Foreign Relations of the United States, Cuba, 1961-1963, Doc. No. 75, page 178) argued strongly against the invasion, citing moral and legal grounds. By supporting this operation, he wrote, "we would be deliberately violating the fundamental obligations we assumed in the Act of Bogota establishing the Organization of American States."

At a meeting on April 4 in a small conference room at the State Department, Senator Fulbright verbally opposed the plan, as described by Arthur Schlesinger in the Pulitzer Prize-winning book A Thousand Days: "Fulbright, speaking in an emphatic and incredulous way, denounced the whole idea. The operation, he said, was wildly out of proportion to the threat. It would compromise our moral position in the world and make it impossible for us to protest treaty violations by the Communists. He gave a brave, old-fashioned American speech, honorable, sensible and strong; and he left everyone in the room, except me and perhaps the President, wholly unmoved."

Five days before D-Day, at a press conference on April 12, Kennedy was asked how far the U.S. would go to help an uprising against Castro. "First," he answered, "I want to say that there will not be, under any conditions, an intervention in Cuba by the United States Armed Forces. This government will do everything it possibly can... I think it can meet its responsibilities, to make sure that there are no Americans involved in any actions inside Cuba... The basic issue in Cuba is not one between the United States and Cuba. It is between the Cubans themselves."

"One further factor no doubt influenced him," wrote Schlesinger, "the enormous confidence in his own luck. Everything had broken right for him since 1956. He had won the nomination and the election against all the odds in the book. Everyone around him thought he had the Midas touch and could not lose. Despite himself, even this dispassionate and skeptical man may have been affected by the soaring euphoria of the new day."

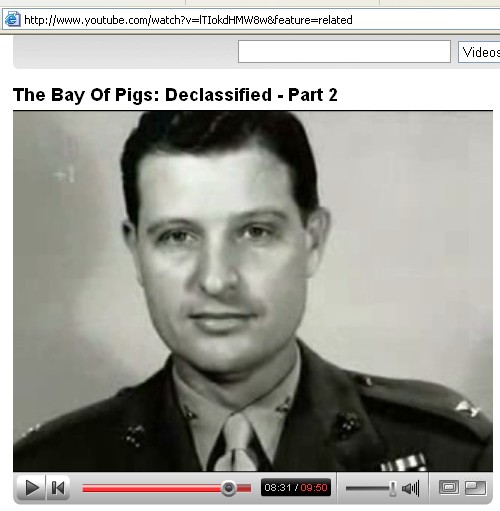

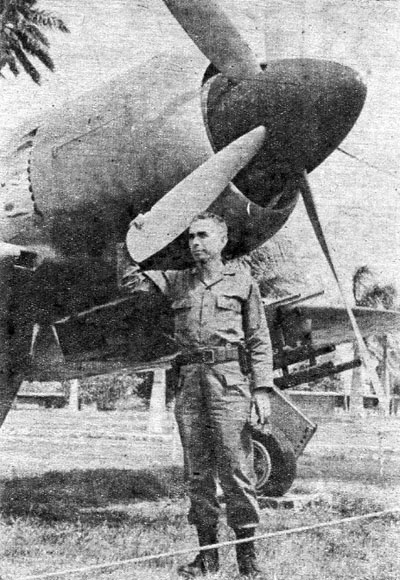

Overall Operation ZAPATA military commander was USMC Colonel Jack Hawkins (1920-):

Colonel Jack Hawkins USMC

spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/JFKhawkins.htm

Jack Hawkins was born in Roxton, Texas in 1920. His family moved to Fort Worth and was a student at the local high school. After graduating from the United States Naval Academy as a second lieutenant he joined the U.S. marines in 1939. He spent time at the marine corps basic school for officers before being sent to China where he served with the fourth marines in Shanghai.

During the Second World War he was captured by the Japanese at Corregidor in the Philippines and spent 11 months as a prisoner of war. He escaped with several other Americans and two Filipino convicts who served as guides, and joined a guerrilla unit for seven months before getting to Australia via submarine in November 1943. In 1945 Hawkins was involved in the invasion of Okinawa.

After the war Hawkins served three years in Venezuela as adviser to the Venezuelan marine corps before returning to Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Hawkins also took part in the Korean War and helped plan the battalion landing plan at Inchon. He then served for three years as an instructor on amphibious landings in marine corps schools. This was followed by a post at the marine corps school in Quantico.

Promoted to full colonel in 1955, he became commander of the Amphibious Forces at Little Creek, Virginia. In September, 1960, Colonel Hawkins was assigned to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). He joined the Cuba Task Force and was given direct responsibility for military training operations. Hawkins was told "that the CIA was planning to land some exile troops in Cuba and they wanted a marine officer with background in amphibious warfare to help them out with this project...."

The Bay of Pigs operation was directed out of the "Miami Station" (also known as "JM/WAVE"), which was the CIA's largest station worldwide. It housed 200 agents who handled approximately 2,000 Cubans. Robert Reynolds was the CIA's Miami station chief from September 1960 to October 1961. He was replaced by career-CIA officer Theodore Shackley, who oversaw Operation Mongoose, Operation 40 (including Porter Goss, Felix Rodriguez, Barry Seal), and others. When Bush became CIA Director in 1976 he appointed Ted Shackley as Deputy Director of Covert Operations. When Bush became Vice President in 1981, he appointed Donald Gregg as his National Security Advisor.

Zapata Oil

Coincidence that entire operation called Zapata?

Oil well platforms used to launch attacks on Cuba: is this to circumvent Lodge act since a platform isn't "U.S. territory"?

Coincidence that operation shifted from Trinidad area in mountains where likely to be successful to swampy Zapata penninsula? WTFO? OPSEC?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zapata_Corporation

Zapata Corporation

Zapata Corporation (NYSE: ZAP) is a holding company based in Rochester, New York and originating from an oil company started by a group including the former United States president George H. W. Bush. Various writers have alleged links between the company and the United States Central Intelligence Agency.

Contents

1. Early business history

2. Connections with the CIA

2.1 FBI and CIA memos

2.2 Allegations by former CIA staff

2.3 Allegations of the involvement of a former CIA officer in the foundation of Zapata

2.4 Bay of Pigs

2.5 Watergate

2.6 Iran-Contra affair

3. Decline

4. Glazer era

5. References

5.1 Public records

5.2 Zapata

5.3 George Bush

5.4 CIA

5.5 Others

6. External links

Early business history

The company traces its origins to Zapata Oil, founded in 1953 by future-U.S. President George H. W. Bush, along with his business partners John Overbey, Hugh Liedtke, Bill Liedtke, and Thomas J. Devine. Bush and Thomas J. Devine were oil-wildcatting associates.[1] Their joint activities culminated in the establishment of Zapata Oil.[1] The initial $1 million investment for Zapata was provided by the Liedtke brothers and their circle of investors, by Bush's father and maternal grandfather-Prescott Bush and George Herbert Walker, and his family circle of friends.

Hugh Liedtke was named president, Bush was vice president; Overbey soon left. In 1954, Zapata Off-Shore Company was formed as a subsidiary of Zapata Oil, with Bush as president of the new company. He raised some startup money from Eugene Meyer, publisher of the Washington Post, and his son-in-law, Phillip Graham.[2][3]

Zapata Off-Shore accepted an offer from an inventor, R. G. LeTourneau, for the development of a mobile but secure drilling rig. Zapata advanced him $400,000, which was to be refundable if the completed rig did not function. If it did function, LeTourneau would get an additional $550,000 together with 38,000 shares of Zapata Off-Shore common stock.

Zapata Corporation split in 1959 into independent companies Zapata Petroleum, headed by the Liedtkes,and Zapata Off-Shore, headed by Bush funded with $800,000.[4] Bush moved his offices and family that year from Midland, Texas to Houston. In 1963, Zapata Petroleum merged with South Penn Oil and other companies to become Pennzoil.

According to a George H. W. Bush-biographer Nicholas King, in the late-1950s and early-1960, Zapata Off-Shore concentrated its business in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Central American coast.[5] The U.S. government began to auction off mineral rights to these areas in 1954. In 1958, drilling contracts with the seven large U.S. oil producers included wells 40 miles (64 km) north of Isabela, Cuba, near the island Cay Sal. In July 1959, Cuba's Batista government was overthrown by Fidel Castro. Zapata also won a contract with Kuwait.

In 1962, Bush was joined in Zapata Off-Shore by a fellow Yale Skull and Bones member, Robert Gow. By 1963, Zapata Off-Shore had four operational oil-drilling - Scorpion (1956), Vinegaroon (1957), Sidewinder, and (in the Persian Gulf) Nola III.

In 1960, Jorge Diaz Serrano of Mexico was put in touch with Bush by Dresser. They created a new company, Perforaciones Marinas del Golfo, aka Permargo, in conjunction with Edwin Pauley of Pan American Petroleum, with whom Zapata had a previous offshore contract. The deal with Pemargo is not mentioned in Zapata's annual reports. A Bush spokesman in 1988 claimed the deal only lasted seven months, from March to September 1960. Zapata sold Nola I to Pemargo in 1964.

By 1964, Zapata Off-Shore had a number of subsidiaries, including: Seacat-Zapata Offshore Company (Persian Gulf), Zapata de Mexico, Zapata International Corporation, Zapata Mining Corporation, Zavala Oil Company, Zapata Overseas Corporation, and a 41% share of Amata Gas Corporation.

Bush ran for the United States Senate in 1964 and lost; he continued as president of Zapata Off-Shore until 1966, when he sold his interest to his business partner, Robert Gow, and ran for the U.S. House of Representatives.

In 1966, William Stamps Farish III, age 28, joined the board Zapata Board.

Zapata's filing records with the U.S.Securities and Exchange Commission are intact for the years 1955-1959, and again from 1967 onwards. However, records for the years 1960-1966 are missing. The commission's records officer stated that the records were inadvertently placed in a session file to be destroyed by a federal warehouse and that a total of 1,000 boxes were pulped in this procedure. The destruction of records occurred either in October 1983 (according to the records officer) or in 1981 shortly after Bush became Vice President of the United States (according to, Wison Carpenter, a record analyst with the commission).

Connections with the CIA

Various writers have suggested that Zapata Off-Shore, and Bush in particular, cooperated with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) beginning in the late 1950s.

FBI and CIA memos

Memo from FBI Special Agent in Texas, regarding call by "GHW Bush of Zapata Off-Shore Drilling Company" received 75 minutes after JFK's murder Memo from J. Edgar Hoover, referring to "Mr. George Bush of the CIA", briefed 24 hours after JFK's murder " [2] Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) memoranda have been offered to show connections between the CIA and George H. W. Bush during his time at Zapata. The first memo names Zapata Off-Shore and was written by FBI Special Agent Graham Kitchel on 22 November 1963, regarding the John F. Kennedy assassination at 12:30 p.m. CST that day. It begins: "At 1:45 p.m. Mr. GEORGE H. W. BUSH, President of the Zapata Off-Shore Drilling Company, Houston, Texas, residence 5525 Briar, Houston, telephonically furnished the following information to writer. .. BUSH stated that he wanted to be kept confidential. .. was proceeding to Dallas, Texas, would remain in the Sheraton-Dallas Hotel."

A second FBI memorandum, written by J. Edgar Hoover, identifies "George Bush" with the CIA. It is dated 29 November 1963 and refers to a briefing given Bush on 23 November. The FBI Director describes a briefing about JFK's murder "orally furnished to Mr. George Bush of the Central Intelligence Agency. .. [by] this Bureau" on " December 20, 1963.

When this second memorandum surfaced during the 1988 presidential campaign, Bush spokespersons (including Stephen Hart) said Hoover's memo referred to another George Bush who worked for the CIA.[6] CIA spokeswoman Sharron Basso suggested it was referring to a George William Bush. However, others described this G. William Bush as a "lowly researcher" and "coast and beach analyst" who worked only with documents and photos at the CIA in Virginia from September 1963 to February 1964, with a low rank of GS-5.[7][8][9] Moreover, this G. William Bush swore an affidavit in federal court denying that Hoover's memo referred to him:

"I have carefully reviewed the FBI memorandum to the Director, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Department of State dated November 29, 1963 which mentions a Mr. George Bush of the Central Intelligence Agency. ... I do not recognize the contents of the memorandum as information furnished to me orally or otherwise during the time I was at the CIA. In fact, during my time at the CIA, I did not receive any oral communications from any government agency of any nature whatsoever. I did not receive any information relating to the Kennedy assassination during my time at the CIA from the FBI. Based on the above, it is my conclusion that I am not the Mr. George Bush of the Central Intelligence Agency referred to in the memorandum." (United States District Court for the District of Columbia, Civil Action 88-2600 GHR, Archives and Research Center v. Central Intelligence Agency, Affidavit of George William Bush, September 21, 1988.)

Allegations by former CIA staff

U.S. Army Brigadier General Russell Bowen wrote that there was a cover-up of Zapata's CIA connections:

Bush, in fact, did work directly with the anti-Castro Cuban groups in Miami before and after the Bay of Pigs invasion, using his company, Zapata Oil, as a corporate cover for his activities on behalf of the agency. Records at the University of Miami, where the operations were based for several years, show George Bush was present during this time.[10]

Another writer[11] quotes four former U.S. intelligence officials saying Bush was involved with the CIA prior to the Bay of Pigs:

Robert T. Crowley and William Corson of the CIA:

Bush was officially considered a CIA business asset, according to Crowley and Corson. "George's insecurities were clay to someone like Dulles", William Corson said. To recruit young George Bush, Robert Crowley explained, Dulles convinced him that "he could contribute to his country as well as get help from the CIA for his overseas business activities." [Bush] was, according to Corson, "perfect at talent spotting and looking at potential recruits for the CIA. You have to remember, we had real fears of Soviet activity in Mexico in the 1950s. Bush was one of many businessmen that would be reimbursed for hiring someone the CIA was interested in, or simply carrying a message." --Chapter 2 page 14

John Sherwood of the CIA:

Bush was at first a tiny part of OPERATION MONGOOSE, the CIA's code name for their anti-Castro operations. According to the late John Sherwood, "Bush was like hundreds of other businessmen who provided the nuts-and-bolts assistance such operations require... What they mainly helped us with was to give us a place to park people that was discreet." --Chapter 2 page 16

An anonymous official connected to "Operation MONGOOSE":

George Bush would be given a list of names of Cuban oil workers we would want placed in jobs... The oil platforms he dealt in were perfect for training the Cubans in raids on their homeland. --Chapter 2 page 16

John Loftus, in his book Secret War quotes former U.S. intelligence officials reporting the same story:

The Zapata-Permargo deal caught the eye of Allan Dulles, who the "old spies" report was the man who recruited Bush's oil company as a part time purchasing front for the CIA. Zapata provided commercial supplies for one of Dulles' most notorious operations: the Bay of Pigs Invasion. --Chapter 16 page 368

Finally, according to Cuban intelligence official Fabian Escalante in The Cuba Project: CIA Covert Operations 1959-62, Jack Crichton and George H.W. Bush raised funds for the CIA's Operation 40.

"Tracy Barnes functioned as head of the Cuban Task Force. He called a meeting on January 18, 1960, in his office in Quarters Eyes, near the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, which the navy had lent while new buildings were being constructed in Langley. Those who gathered there included the eccentric Howard Hunt, future head of the Watergate team and a writer of crime novels; the egocentric Frank Bender, a friend of Trujillo; Jack Esterline, who had come straight from Venezuela where he directed a CIA group; psychological warfare expert David A. Phillips, and others. The team responsible for the plans to overthrow the government of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954 was reconstituted, and in the minds of all its members this would be a rerun of the same plan. Barnes talked at length of the goals to be achieved. He explained that Vice-President Richard Nixon was the Cuban "case officer", and had assembled an important group of businessmen headed by George Bush [Snr.] and Jack Crichton, both Texas oilmen, to gather the necessary funds for [Operation 40]. Nixon was a protege of Bush's father [Prescott], who in 1946 had supported Nixon's bid for congress. In fact, [Presott] Bush was the campaign strategist who brought Eisenhower and Nixon to the presidency of the United States. With such patrons, Barnes was certain that failure was impossible." --Pages 43-44

Fabian Escalante was in the Department of State Security (G-2) in Cuba in 1960. At the time of the Bay of Pigs, Escalante was head of a counter-intelligence unit and was part of a team investigating a CIA operation called Sentinels of Liberty, an attempt to recruit Cubans willing to work against Castro. His information about Bush apparently comes from a counterintelligence operation against Tracy Barnes of the CIA.

Allegations of the involvement of a former CIA officer in the foundation of Zapata

On January 8, 2007, newly released internal CIA documents revealed that Zapata had in fact emerged from Bush's collaboration with a covert CIA officer in the 1950s. According to a CIA internal memo dated November 29, 1975, Zapata Petroleum began in 1953 through Bush's joint efforts with Thomas J. Devine, a CIA staffer who had resigned his agency position that same year to go into private business, but who continued to work for the CIA under commercial cover. Devine would later accompany Bush to Vietnam in late 1967 as a "cleared and witting commercial asset" of the agency, acted as his informal foreign affairs advisor, and had a close relationship with him through 1975.[12]

Bay of Pigs

George Bush on Zapata oil rig, c.1963The CIA codename for the Bay of Pigs invasion of April 1961 was "Operation ZAPATA".[13] Through his work with Zapata Off-Shore, Bush is alleged to have come into contact with Felix Rodriguez, Barry Seal, Porter Goss, and E. Howard Hunt, around the time of the Bay of Pigs operation.[14]

CIA liaison officer Col. L. (Leroy) Fletcher Prouty alleges[15] that Zapata Off-Shore provided or was used as cover for two of the ships used in the Bay of Pigs invasion: the Barbara J and Houston. Prouty claims he delivered two ships to an inactive Naval Base near Elizabeth City, North Carolina, for a CIA contact and he suspected very strongly that George Bush must have been involved:

They asked me to see if we could find - purchase - a couple of transport ships. We got some people that were in that business, and they went along the coast and they found two old ships that we purchased and sent down to Elizabeth City and began to load with an awful lot of trucks that the Army was sending down there. We deck-loaded the trucks, and got all of their supplies on board. Everything that they needed was on two ships. It was rather interesting to note, looking back these days, that one of the ships was called the Houston, and the other ship was called the Barbara J. Colonel Hawkins had renamed the program as we selected a name for the Bay of Pigs operation. The code name was "Zapata." I was thinking a few months ago of what a coincidence that is. When Mr. Bush graduated from Yale, back there in the days when I was a professor at Yale, he formed an oil company, called "Zapata", with a man, Lieddke, who later on became president of Pennzoil. But the company that Lieddke and Mr. Bush formed was the Zapata Oil Company. Mr. Bush's wife's name is Barbara J. And Mr. Bush claims as his hometown Houston, Texas. Now the triple coincidence there is strange; but I think it's interesting. I know nothing about its meaning. But these invasion ships were the Barbara J and the Houston, and the program was "Zapata." George Bush must have been somewhere around.[16]

John Loftus writes: "Prouty's credibility, however has been widely attacked because of his consultancy to Oliver Stone's film JFK." but notes on page 598 that: "While his credibility has suffered greatly because of his consultancy to Oliver Stone's film JFK, his recollections about the CIA supply mission have been confirmed by other sources."[17]

Nevertheless, researcher James K. Olmstead claims to have discovered a CIA memorandum which states that the boats were leased, not purchased, by the Garcia Line Corporation with offices in Havana and New York City. The owners were Alfredo Garcia and his five sons. The CIA was using the Rio Escondido for "exfiltrating anti-Castro leaders......prior to 1961 BOP planning." It had brought out Nino Diaz, and Manolo Ray. Its captain Gus Tirado was well known to the CIA. Eduardo Garcia met with two CIA agents in NYC and D.C. to arrange the use of the Garcia ships for the invasion. The alleged price was $600.00 per day per ship plus fuel, food and personnel.

Eduardo selected and hired 30 men who were "executioners for Batista" Miro Cardona of the Frente and the CIA did not like the choice of men hired to protect the Garcia ships. "Nobody questioned that Eduardo was coming along with the expedition. "I'm going to be in charge of my ships", he said.

Memorandum From the Chief of WH/4/PM, Central Intelligence Agency (Hawkins) to the Chief of WH/4 of the Directorate for Plans (Esterline) The Barbara J (LCI), now enroute to the United States from Puerto Rico, requires repairs which may take up to two weeks for completion. The sister ship, the Blagar, is outfitting in Miami, and its crew is being assembled. It is expected that both vessels will be fully operational by mid-January at the latest. In view of the difficulty and delay encountered in purchasing, outfitting and readying for sea the two LCI's, the decision has been reached to purchase no more major vessels, but to charter them instead. The motor ship, Rio Escondido (converted LCT) will be chartered this week and one additional steam ship, somewhat larger, will be chartered early in February. Both ships belong to a Panamanian Corporation controlled by the Garcia family of Cuba, who are actively cooperating with this Project. These two ships will provide sufficient lift for troops and supplies in the invasion operation.

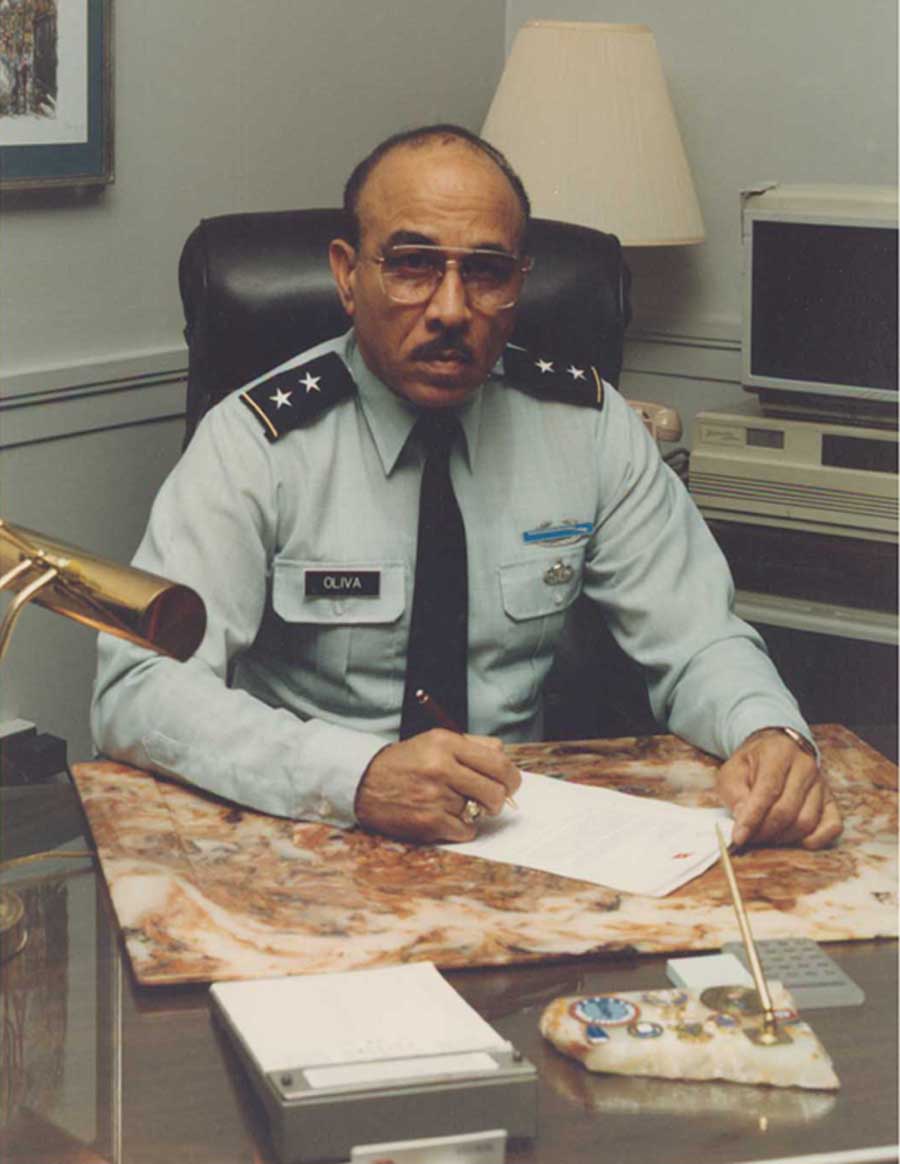

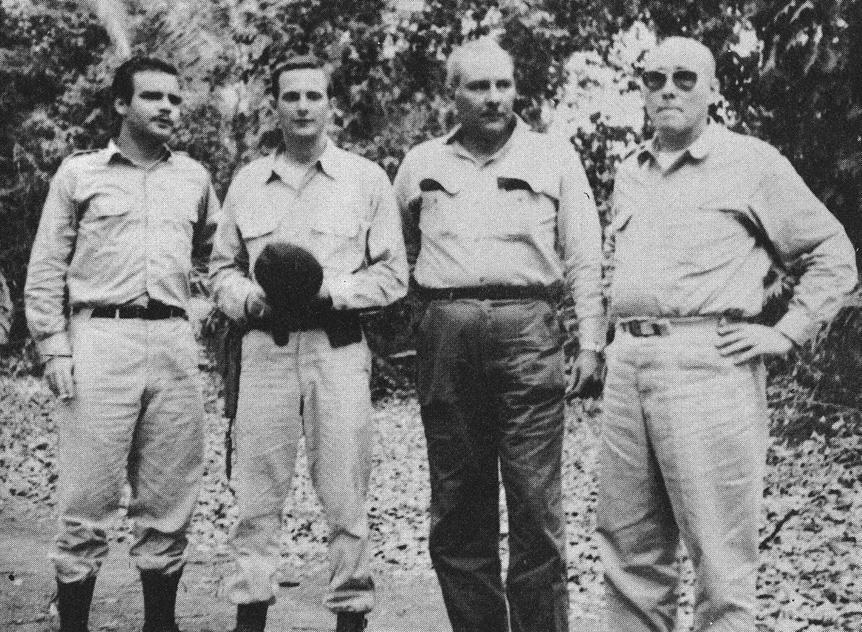

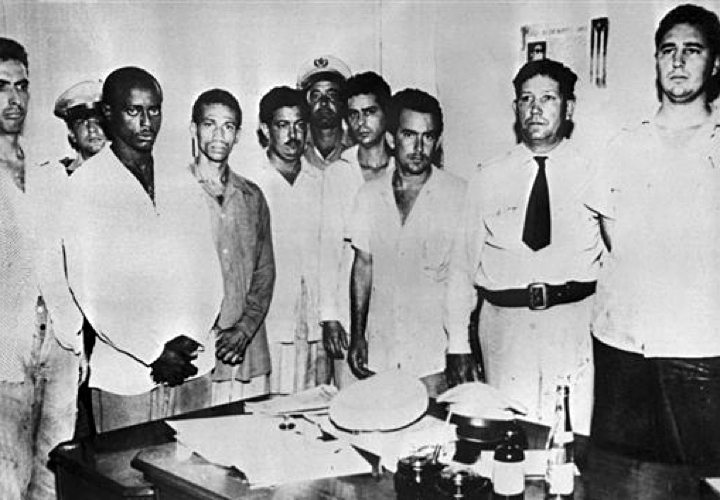

Felix Rodriguez, Porter Goss, Barry Seal, and others, Mexico City 22 January 1963

The Bay of Pigs operation was directed out of the "Miami Station" (also known as "JM/WAVE"), which was the CIA's largest station worldwide. It housed 200 agents who handled approximately 2,000 Cubans. Robert Reynolds was the CIA's Miami station chief from September 1960 to October 1961. He was replaced by career-CIA officer Theodore Shackley, who oversaw Operation MONGOOSE, Operation 40 (including Porter Goss, Felix Rodriguez, Barry Seal), and others. When Bush became CIA Director in 1976 he appointed Ted Shackley as Deputy Director of Covert Operations. When Bush became Vice President in 1981, he appointed Donald Gregg as his National Security Advisor.

Kevin Phillips[18] discusses George Bush's "highly likely" peripheral role in the Bay of Pigs events. He points to the leadership role of Bush's fellow Skull & Bones alumni in organizing the operation. He notes an additional personal factor for Bush: the Walker side of the family (who initially funded Zapata Corporation) had apparently lost a small fortune when Fidel Castro nationalized their West Indies Sugar Co. Edwin Pauley was "known for CIA connections", according to Phillips, it was Pauley who put Pemargo's Diaz and Bush together.

Watergate

Phillips and others have detailed subsequent involvement by Zapata associates in the Watergate affair. George Bush, as Richard Nixon's ambassador to the United Nations, allegedly urged his former Zapata partner Bill Liedtke to launder $100,000 to the White House plumbers. After Nixon's 1972 re-election, he appointed Bush as Chairman of the Republican Party National Committee. When the laundering was exposed, those involved included several CIA officials: E. Howard Hunt, Frank Sturgis, Eugenio Martínez, Virgilio González, and Bernard Barker. A discussion of the laundering appears on the Nixon tapes for June 23, 1973.[19]

Iran-Contra affair

Note from Bush to Rodriguez, December 1988

Michael Maholy alleges[20] that Zapata Off-Shore was used as part of a CIA drug-smuggling ring to pay for arming Nicaraguan Contras in 1986-1988, including Rodriguez, Eugene Hasenfus and others. Mahony claims Zapata's oil rigs were used as staging bases for drug shipments, allegedly named "Operation Whale Watch." Mahony allegedly worked for Naval Intelligence, U.S. State Department and CIA for two decades.

Decline

Zapata, under Robert Gow's direction, acquired a controlling interest in the United Fruit Company in 1969. Robert's father, Ralph Gow, was on United Fruit's board of directors.

Gow apparently left Zapata in 1970. He took with him from Zapata Peter C. Knudtzon. Ties to the Bush family continued. In 1971 both Jeb Bush and George W. Bush worked for Gow's new company, Stratford of Texas (also known as Stratford of Houston). Stratford imported tropical plants. According to Knudtzon, George W. Bush reportedly flew for Stratford to Florida and Guatemala.[21] Stratford evidently had ties to a large commercial plantation in La Democracia, Huehuetenango, Guatemala.

In the 1970s, under chairman and CEO William Flynn, Zapata expanded its business to include subsidiaries in dredging, construction, coal mining, copper mining and fishing.

By the late 1970s, saddled with weak operations, high debt and low return on investment, the company again began undergoing changes in management and direction. Lead by John Mackin, who succeeded William Flynn, the company began selling off some of those businesses and refocused on offshore oil and gas exploration and production.

In 1982 chief operating officer Ronald Lassiter assumed the role of CEO, and presided over a decade of loss-making brought on by the collapse of oil prices. Zapata Off-shore became Zapata Corporation in 1982. Its stock performed poorly. By 1986 Zapata was one of the bad loans that shook the foundations of San Francisco-based Bank of America, with a debt of more than $500 million and a fiscal year loss of $250 million. The company announced several restructurings during those years and managed to stave off bankruptcy, but continued to incur major losses. In 1990 the oil drilling company proposed selling its entire fleet of offshore drilling rigs to focus solely on fishing. The company had not had a profitable quarter in more than five years.

Zapata Offshore continued on as an offshore drilling company until the early 1990s when it was purchased by Arethusa Offshore which a few years later sold the rigs to Diamond Offshore. Still struggling with debt by 1993, Zapata signed a deal with Norex America to raise more than $100 million through a loan and stock sale. But financier Malcolm Glazer, owner of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers NFL franchise and at the time owner of 40 percent of Zapata, did not want his holdings diluted and filed a lawsuit to block the deal.

Glazer era

By 1994 the company had come under Glazer's control, after a proxy fight. Glazer became chairman of Zapata, replacing Ronald Lassiter, and in 1995 Avram Glazer was named CEO and president of Zapata. De facto headquarters moved from Houston to Rochester, New York. It no longer engaged in exploration, but owned several natural gas service companies. It also produced protein products from the menhaden fish. In subsequent years Zapata sold its energy-related businesses and focused on marine protein.

Between 1998 and 2000, Zapata tried to position itself as an internet media company under the "zap.com" name. The company's stock boomed and crashed along with other dot-coms, and in 2001 the company conducted a 1 for 10 reverse stock split. The venture was cited by many investment journalists as an example of a company jumping on the internet bandwagon without any relevant experience. This period is probably best remembered for Zapata's unsolicited (and unsuccessful) takeover bid of the Excite internet portal.[22]

During this period Zapata also built up a controlling stake in Safety Components International, a manufacturer of air bag fabrics and cushions.

On December 2, 2005, Zapata Corporation Chairman, Avie Glazer, announced the sale of 4,162,394 shares, 77.3%, of Safety Components International to Wilbur L. Ross, Jr. for $51.2 million. The company sold its remaining stock in Omega Proteine on December 1, 2006, leaving it with no active subsidiary.

References

1.^ a b Withheld (sanitized, unclassified document), Central Intelligence Agency (29 November 1975). "Memorandum: To: Deputy Director of Operations; Subject: Messrs. George Bush and Thomas J.". NARA Record Number: 104-10310-10271. http://www.maryferrell.org/mffweb/archive/viewer/showDoc.do?docId=12758&relPageId=2.

2.^ Hasty, Michael (February 5, 2004). "Secret admirers: The Bushes and the Washington Post". Online Journal. http://web.archive.org/web/20040405042234/http://onlinejournal.com/Media/020504Hasty/020504hasty.html.

3.^ Perin, Monica (April 23, 1999). "Adios, Zapata! Colorful company founded by Bush relocates to N.Y.". Houston Business Journal. http://houston.bizjournals.com/houston/stories/1999/04/26/story2.html.

4.^ "Zapata Oil Files, 1943-1983". George Bush Personal Papers. George Bush Presidential Library. Archived from the original on 2007-08-20. http://web.archive.org/web/20070820095146/http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/find/Doncol1/bushpaps.html#Series:%20Zapata%20Oil%20Files,%201943-1983.

5.^ King, Nicholas (1980). George Bush: A Biography. Dodd Mead. ISBN 0396079199.

6.^ "John Fitzgerald Kennedy". American Patriot Friends Network. www.apfn.org/apfn/jfk2.htm.

7.^ "Bush called FBI when JFK died". The Houston Chronicle. December 21, 1991. newsmine.org/archive/deceptions/assassinations/jfk/bush-calls-fbi-on-jfk-assasination-cia-briefing.txt.

8.^ [www.voxfux.com/features/bush_world_class_criminal.html George Bush: World Class Monster]

9.^ Date: Thu, 4 January 1996 20:14:32 GMT

10.^ Russell Bowen (1991). [1] The Immaculate Deception: The Bush Crime Family Exposed.

11.^ Prelude to Terror Joseph J. Trento

12.^ [2],[3],[4]

13.^ See Beschloss, p.89

14.^ Porter & 'the boys': Goss Made His "Bones" on CIA Hit Team

15.^ in the book, UNDERSTANDING SPECIAL OPERATIONS (1989) and on his website

16.^ Chp 1, Part III: 1961-1963: Prouty's Military Experiences 1941-1963

17.^ John-Loftus.com

18.^ American Dynasty

19.^ White

20.^ CONTACT: The Phoenix Project, March 26, 1996

21.^ Chapter 3: The 1970s

22.^ Suzanne Galante (May 21, 1998). "Excite rejects Zapata's bid". CNET News.com. http://news.cnet.com/2100-1001-211454.html.

Public records

SEC filings of Zapata Corporation

Zapata Offshore Annual Reports, Microform Reading Room, Library of Congress.

Transcript and audioof a "smoking gun" tape of Nixon telling Haldeman and Ehrlichman about the "Bay of Pigs" and "Texans."

National Security Archives documentation of GHW Bush's CIA involvement in the early 1960s.

United States District Court for the District of Columbia, Civil Action 88-2600 GHR, Archives and Research Center v. Central Intelligence Agency, Affidavit of George William Bush, September 21, 1988.

George Bush personal papers

Zapata

"Adios, Zapata! Colorful company founded by Bush relocates to N.Y.", Houston Business Journal, April 26, 1999

Franklin, H. Bruce, "Net Losses", Mother Jones, March 2006 - extensive article on role of Menhaded in ecosystem and possible results of overfishing. Retrieved 21 February, 2006

George Bush

Kevin Philips, Dynasty: Aristocracy, Fortune and the Politics of Deceit in the House of Bush, (2004), esp. pp.200-208.

Russell Bowen, The Immaculate Deception: The Bush Crime Family Exposed (1991).

Joseph McBride, "The Man Who Wasn't There: 'George Bush,' CIA Operative", The Nation, July 16/23, 1988, p. 42.

Joseph McBride, "Where Was George?", The Nation, August 13/20, 1988, on the whereabouts of GHW Bush on 22 November 1963.

Nicolas King, George Bush: A Biography.

Webster Tarpley & Anton Chaitkin, George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography, Chapter 8.2 (1991), and "Bush as a covert CIA operative during the early 1960s". Tarpley and Chaitkin are associated with Lyndon LaRouche.

Laura Hanning 2004, Study of Evil - A World Reappraised: supporting documents, photos, letters, part III George Herbert Walker Bush

Anthony L. Kimery, "George Bush and the CIA: In the Company of Friends", Covert Action Quarterly, Summer, 1992.

"George HW Bush and Felix Rodriguez: the tale of two old friends"

The Mafia, CIA & George [HW] Bush, Pete Brewton, S.P.I. Books, 1992

CIA

Robert T. Crowley of the CIA (Quoted by Joseph J. Trento) Prelude to Terror (2005)

William Corson of the CIA (Quoted by Joseph J. Trento) Prelude to Terror (2005)

John Sherwood of the CIA (Quoted by Joseph J. Trento) Prelude to Terror (2005)

Prelude to Terror Chapter 2 pg. 13 Recruiting George H. W. Bush [5]

Richard Bissell, Reflections of a Cold Warrior, (Yale University Press, 1996).

David Atlee Phillips, The Night Watch.

E. Howard Hunt, Give Us This Day (New Rochelle: Arlington Press, 1973)

Michael R. Beschloss, The Crisis Years: Kennedy and Khrushchev, 1960-63 (New York: Edward Burlingame Books, 1991), p. 89 refers to "Operation ZAPATA" as the codename for the Bay of Pigs operation.

Others

Leroy Fletcher Prouty, The Secret Team (1973).

Michael Maholy (of Yankton, SD)[6]

Daniel Yergin, The Prize, (1991).

Rodney Stich (former FAA investigator) Defrauding America (1994), and The Drugging of America (1999).

External links

Zapata Corporation

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zapata_Corporation"

Categories: Companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange | Agriculture companies of the United States | Family businesses

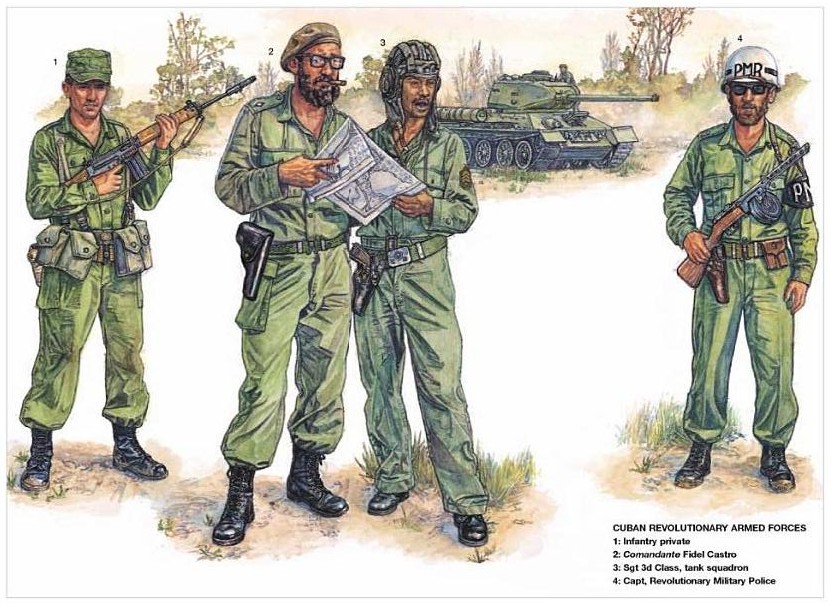

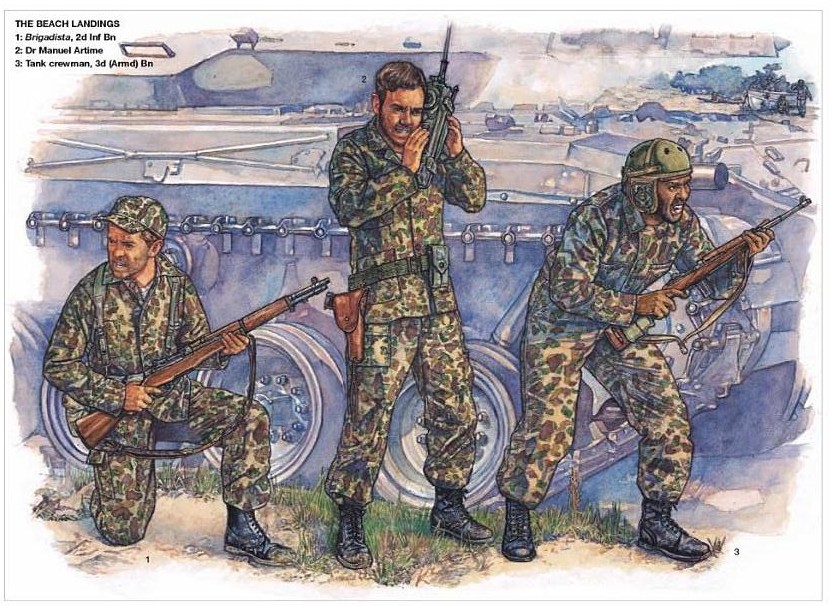

Order of Battle

CIA's Assault Brigade 2506

>1,500 Cuban exiles

(c. 1,300 landed)

2 CIA agents

www.seeingred.com/Copy/2.5_cubasuit2.html

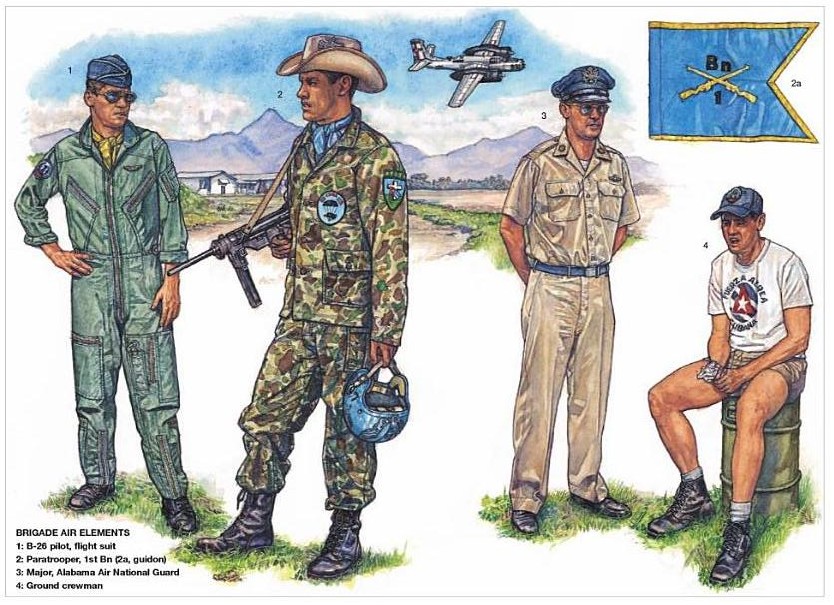

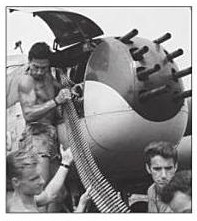

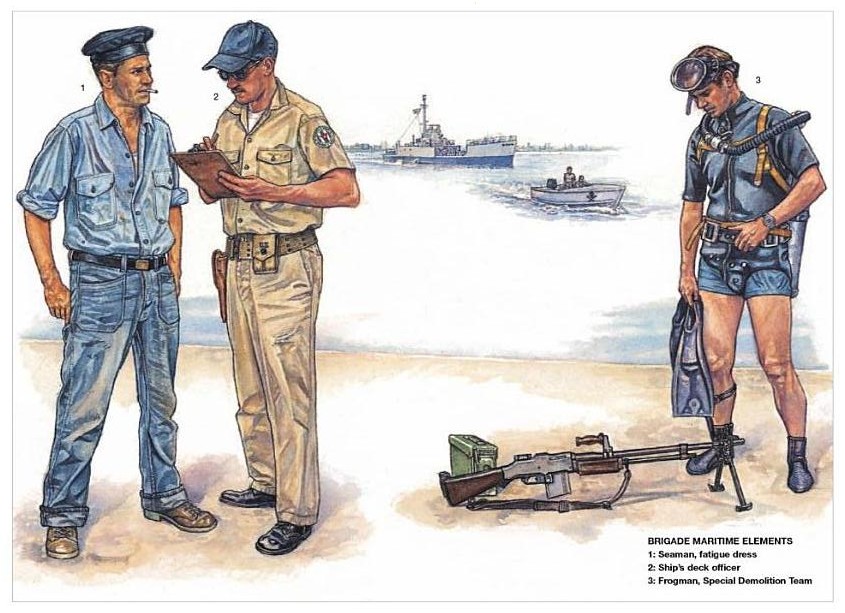

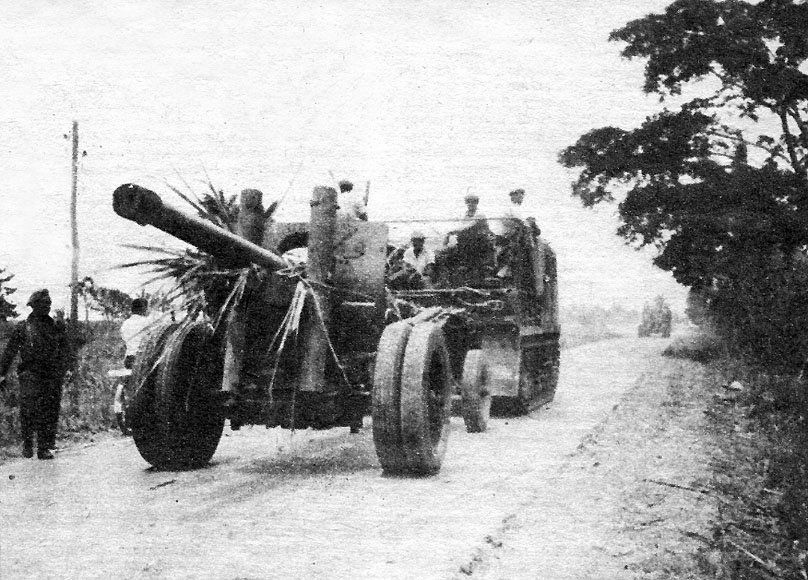

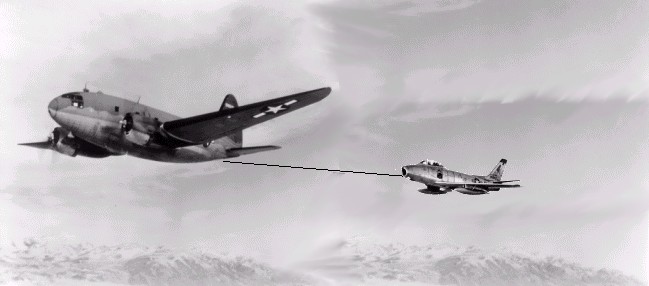

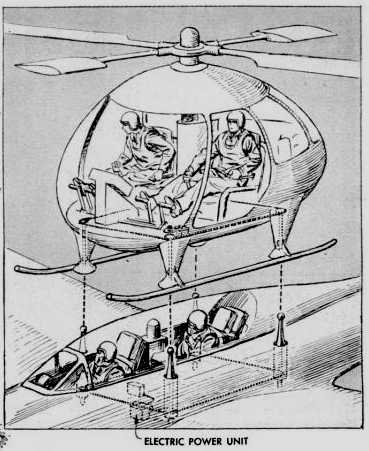

It had five transport gunboats, two modified LCI artillery war units, three LCV landing craft for transporting heavy equipment and four LCVP troop-carrier landing craft. For air operations, the mercenaries were backed by 16 x B-26 The members of the mercenary brigade received military training from American instructors at bases in the United States, Guatemala and Puerto Rico. They received monthly allowances to support their families provided by the United States government which spent a total of 45 million dollars to finance the operation.

http://timelines.com/1961/4/16/cia-brigade-2506-invasion-fleet-converges-on-rendezvous-point-zulu-south-of-cuba

The Brigade consisted of five battalions with a total strength of 1,258 infantrymen and approximately 300 men for the supply services. The battalions had the actual strength of a United States infantry company and almost no heavy weapons.

There was no artillery and the only support was given

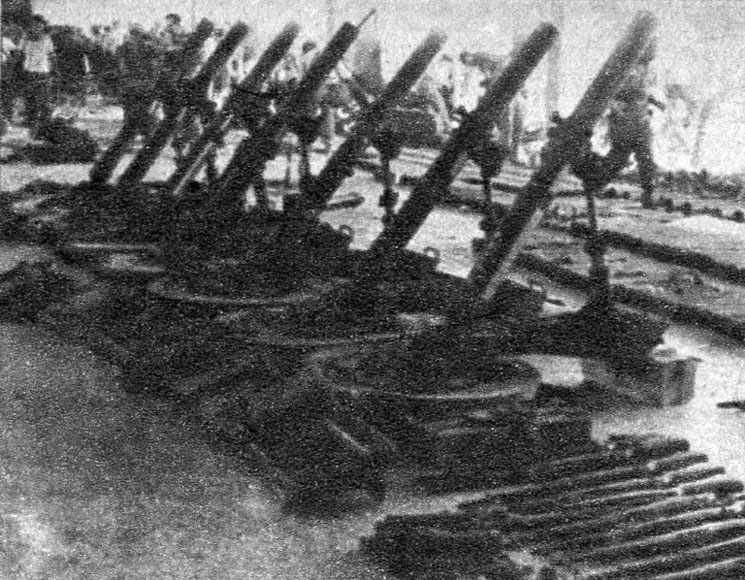

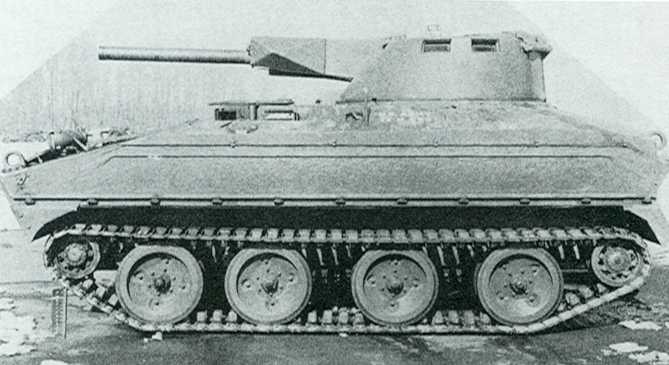

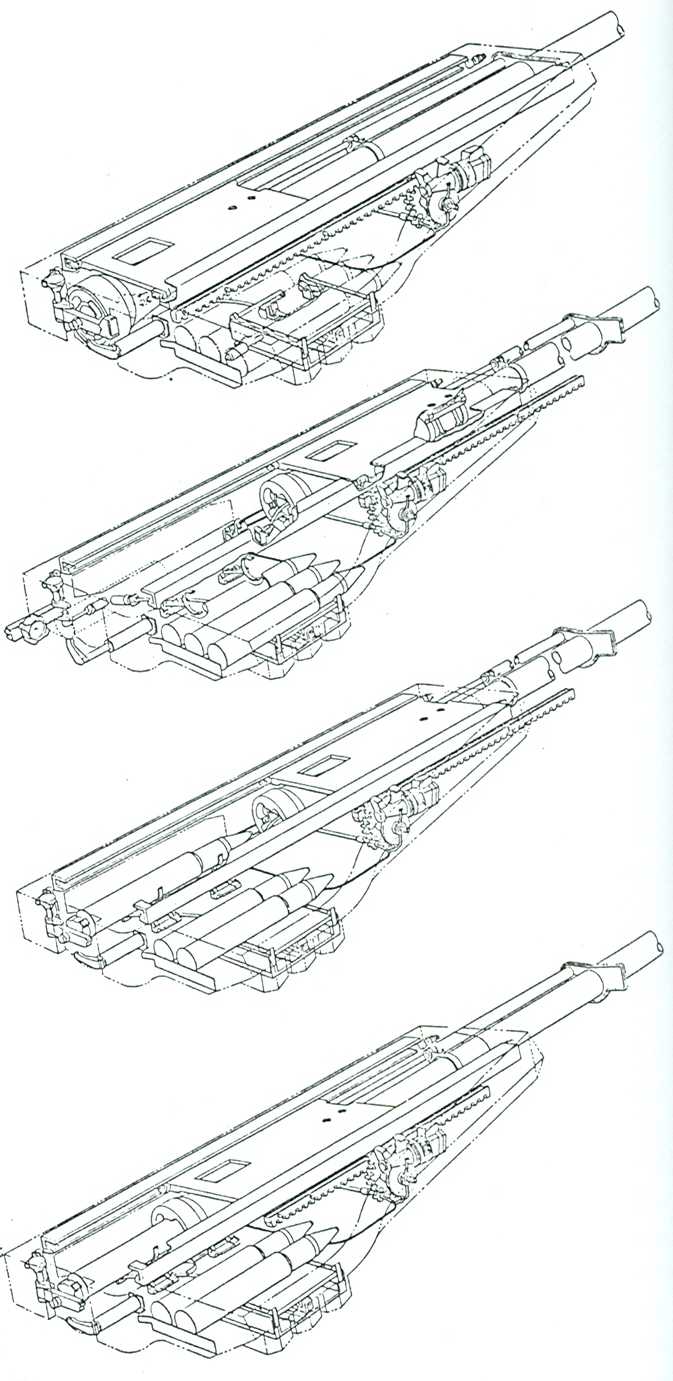

fighter bomber planes, 6 x C-46, 8 x C-54 transport planes and 2 x Catalina seaplanes. They had 5 x M-41 Sherman Walker BullDog tanks, with 76-millimeter guns; 10 armored cars equipped with .50-caliber machine-guns; 75 x bazookas; 60 x mortars of different caliber; 21 x recoilless cannons, 75-millimiter and 57-millimeter; 44 x machine-guns .50-caliber and 39 x light and heavy machine-guns .30-caliber; 8 x flame-throwers; 22,000 hand-grenades; 108 x Browning automatic rifles; 470 x M3 submachine-guns; 635 x Garand rifles and M1 carbines; 465 x pistols and other light weapons.

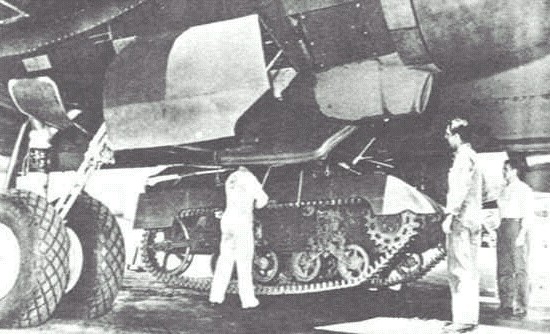

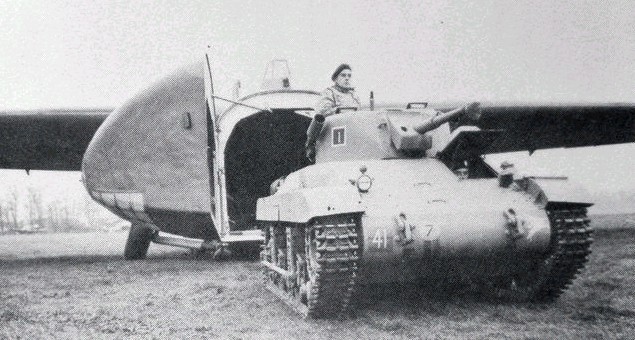

by six Mark IV Sherman tanks 5 x M41 Walker BullDog light tanks which joined the invasion in three LCTs and were landed before the infantrymen. Apparently the lack of sea transports forced the planners of the operation to reload the LCTs with the motorized equipment, land it , and then return to the troop transports to pick up the infantrymen. Each LCT carried two tanks, two trucks, and two jeeps. The infantrymen were armed with Garand [8-shot, 7.62mm x 82mm] semi-automatic rifles and M1 [.30 caliber short cartridge] carbines plus heavy weapons consisting of 6 x 60mm [light] mortars, 6 x 81mm [medium] mortars, and 6 x 107mm [4.2 inch heavy] mortars. A number of 57mm recoilless rifles and .50 caliber [12.7mm heavy] machine guns was also used by the expeditionary forces.

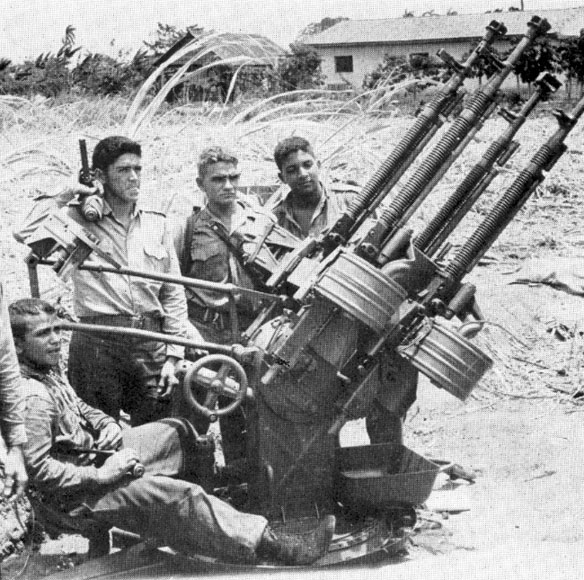

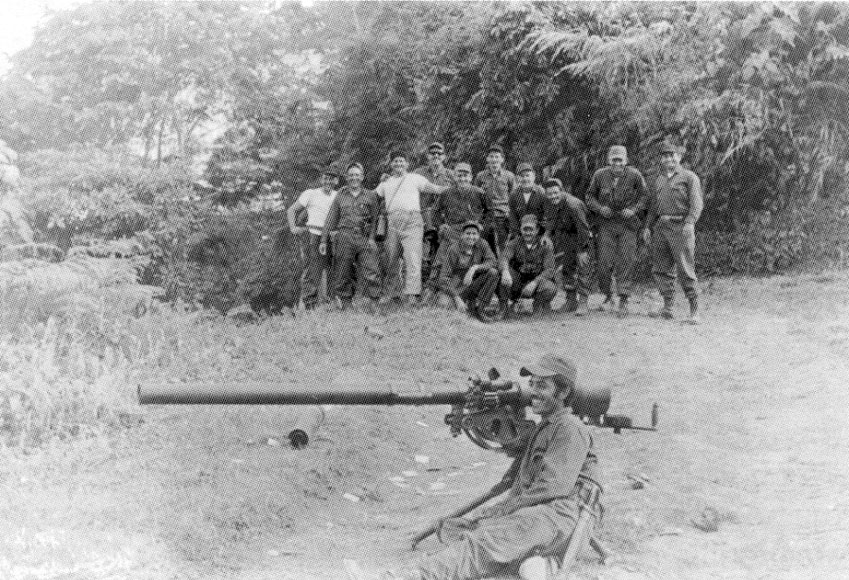

2506 Mortars

In less than 72 hours, the Cuban revolutionary forces overwhelmingly crushed the powerful invading mercenary brigade.

latinamericanstudies.org/baypigs-2.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bay_of_Pigs_Invasion

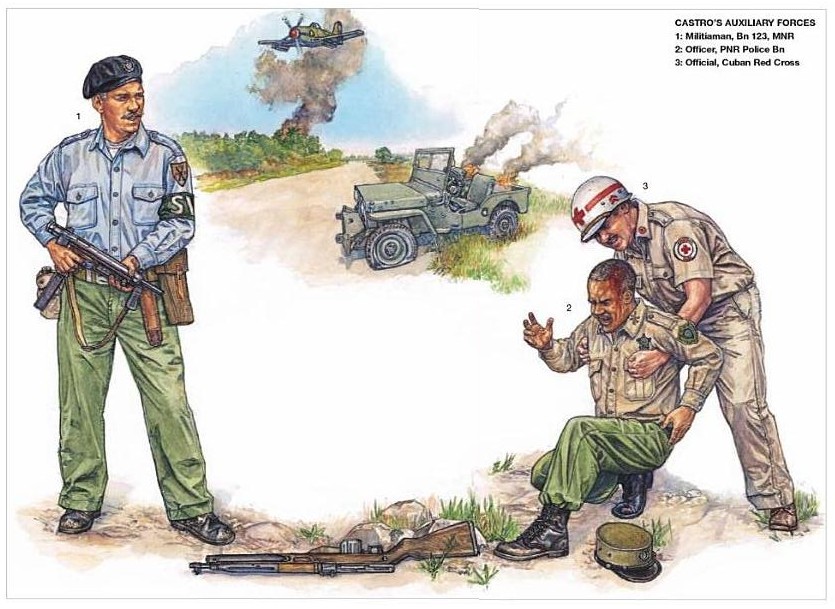

Castro's Cuban FAR

c. 25,000 army

c. 200,000 militia

c 9,000 armed police

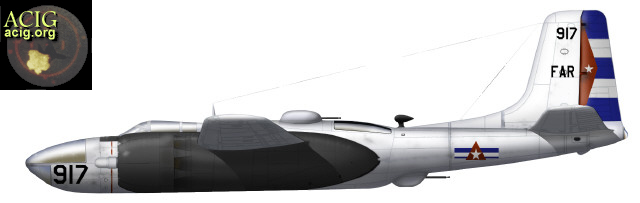

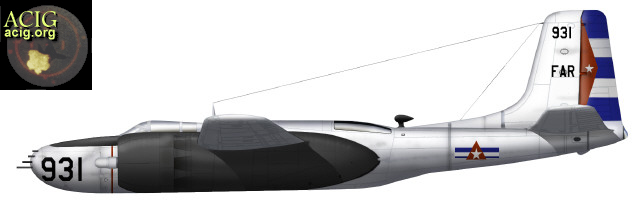

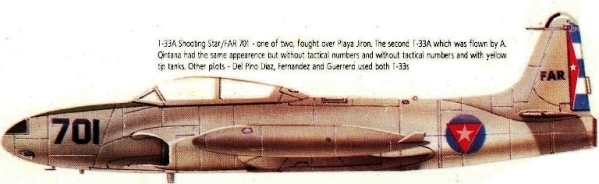

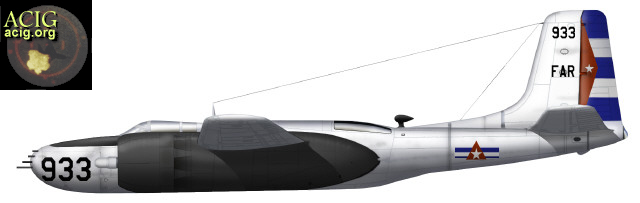

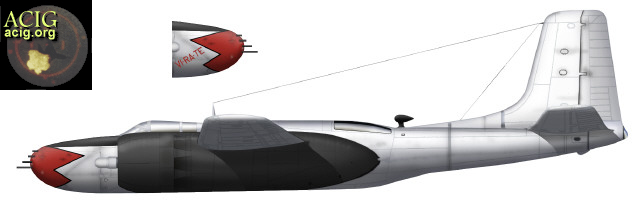

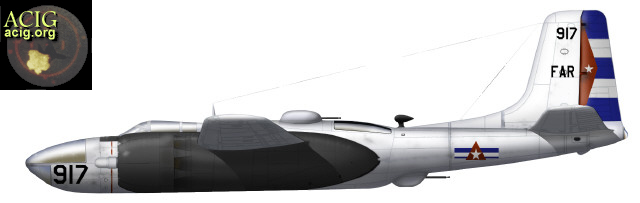

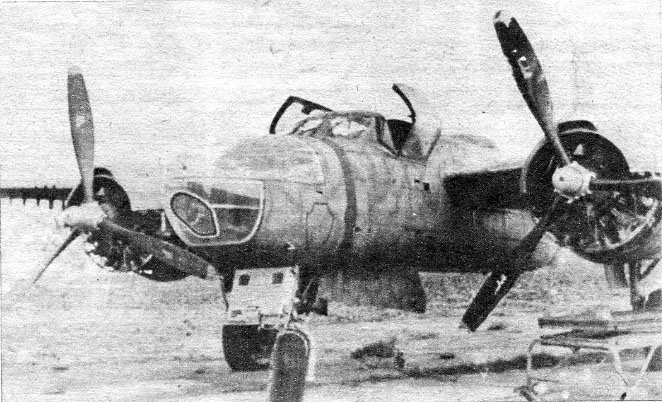

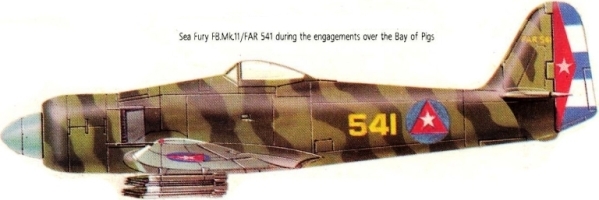

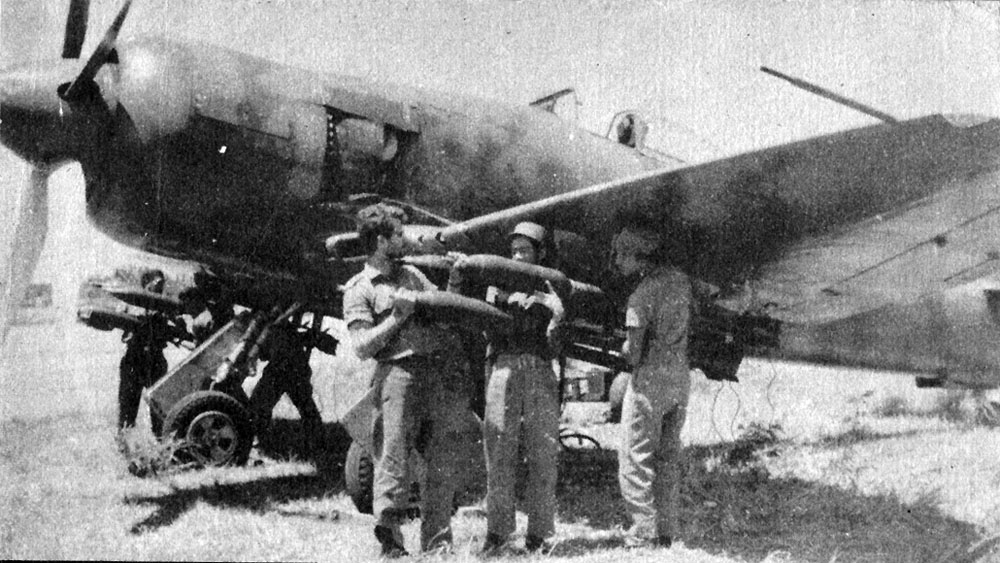

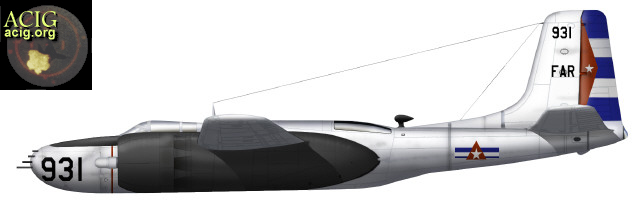

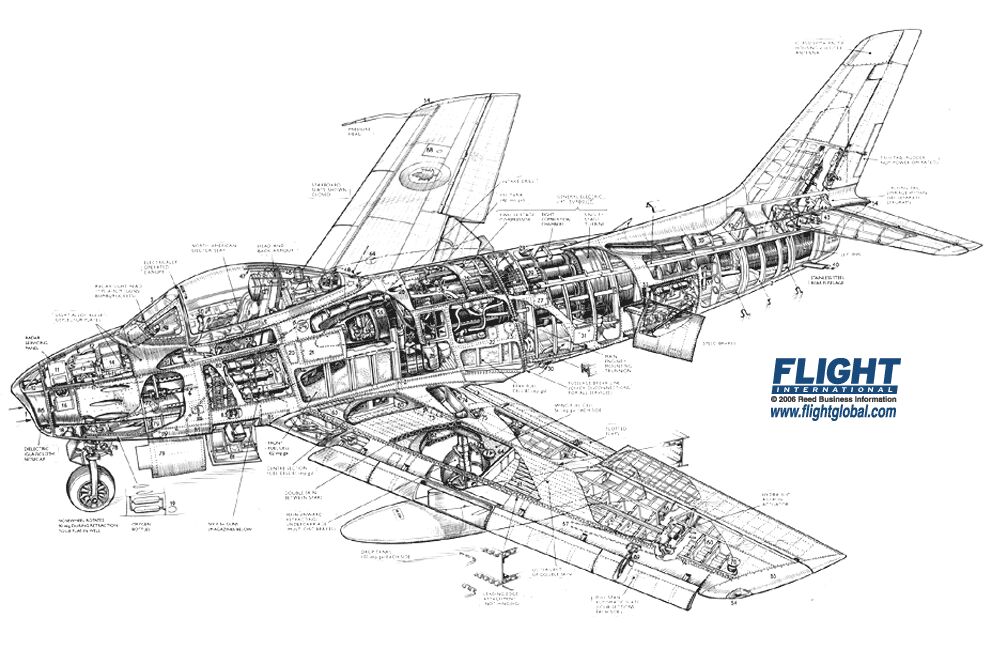

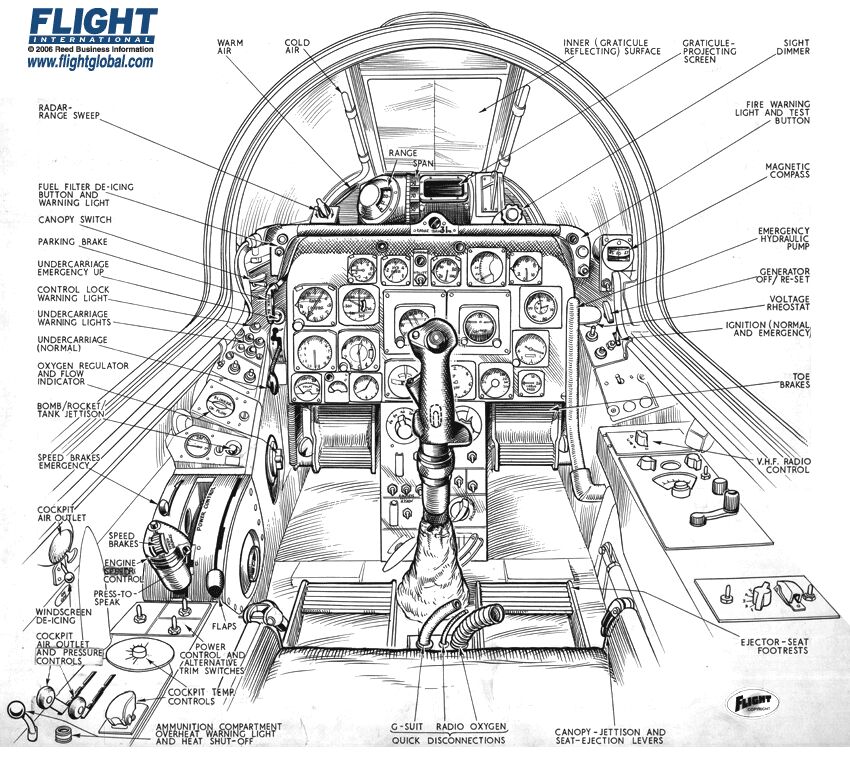

In early 1961, Cuba's army possessed Soviet-designed T-34 and IS-2 Stalin tanks, SU-100 self-propelled [turretless] "tank destroyers", 122mm howitzers, other artillery and small arms, plus Italian 105 mm howitzers. The Cuban air force armed inventory included Douglas B-26C Invader light bombers, Hawker Sea Fury fighters, and Lockheed T-33 jets, all remaining from the Fuerza Aérea del Ejército de Cuba (FAEC), the Cuban air force of the Batista government.[14]

Anticipating an invasion, Che Guevara stressed the importance of an armed civilian populace, stating "all the Cuban people must become a guerrilla army, each and every Cuban must learn to handle and if necessary use firearms in defense of the nation."[18]

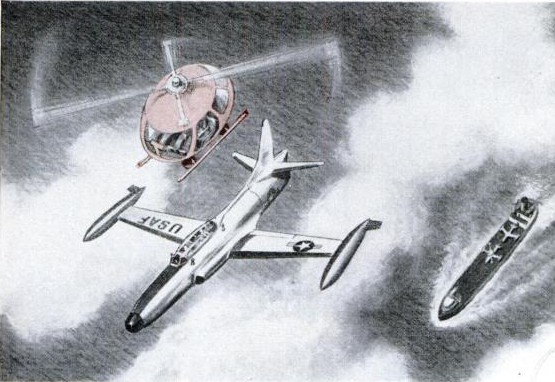

Following the air strikes on airfields on April 15, 1961, the FAR managed to prepare for armed action at least four T-33s, four Sea Furies and five or six B-26s. All three types could be armed with machine guns and rockets for air-to-air combat and for strafing of ships and ground forces. CIA planners had reportedly failed to discover that the U.S.-supplied T-33 jets had long been armed with M3 [.50 caliber heavy] machine guns. The Sea Furies and B-26s could also carry bombs, for attacks against ships and tanks.[40]

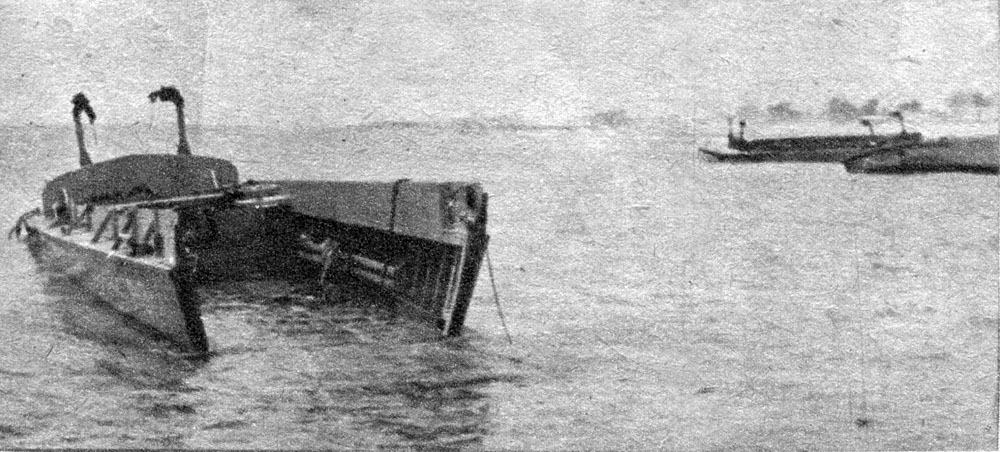

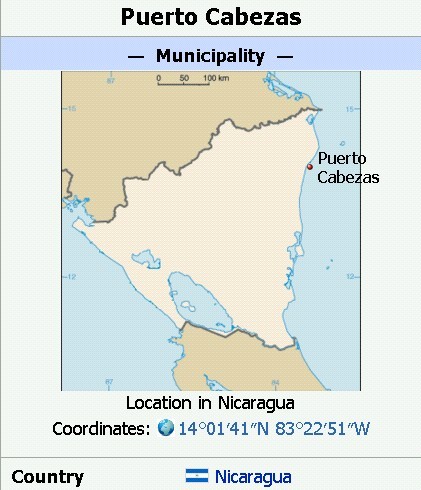

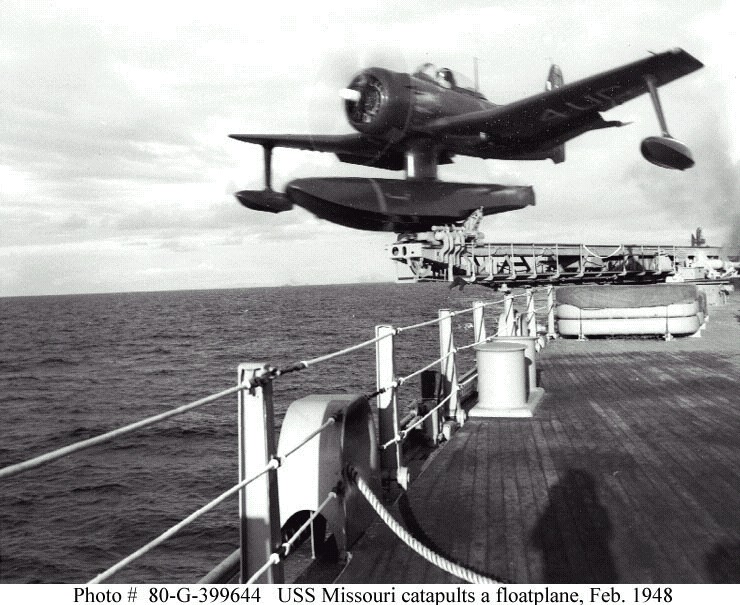

Late on April 16, 1961, the CIA/Assault Brigade 2506 invasion fleet converged on

"Rendezvous Point Zulu", about 65 km (40 miles) south of Cuba, having sailed from Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua where they had been loaded with troops and other materiel, after loading arms and supplies at New Orleans. The U.S. Navy operation was code-named BUMPY ROAD, having been changed from CROSSPATCH on 1 April 1961[11]. The fleet, cryptically labelled the "Cuban Expeditionary Force" (CEF), included five 2,400-ton (empty weight) freighter ships chartered by the CIA from the Garcia Line and outfitted with anti-aircraft guns. Four of the freighters, Houston (code name Aguja), Río Escondido (code name Balena), Caribe (code name Sardina), and Atlántico (code-name Tiburon), were planned to transport about 1,400 troops in 7 battalions of troops and armaments near to the invasion beaches. The fifth freighter, Lake Charles, was loaded with follow-up supplies and some Operation 40 infiltration personnel. The freighters sailed under Liberian ensigns. Accompanying them were two LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry) "purchased" from Zapata Corporation then outfitted with heavy armament at Key West, then exercises and training at Vieques Island. The LCIs were Blagar (code-name Marsopa) and Barbara J (code-name Barracuda), sailing under Nicaraguan ensigns.

The CEF ships were individually escorted (outside visual range) to Point

Zulu by U.S. Navy destroyers USS Bache, USS Beale, USS Conway, USS Cony, USS Eaton, USS Murray, USS Waller. A task force had already assembled off the Cayman Islands, including aircraft carrier USS Essex with task force commander John A. Clark (Admiral) onboard, helicopter assault carrier USS Boxer [EDITOR logical to assume with marines onboard], destroyers USS Hank, USS John W. Weeks, USS Purdy, USS Wren, and submarines USS Cobbler and USS Threadfin. Command and control ship USS Northampton and carrier USS Shangri-La were also reportedly active in the Caribbean at the time. USS San Marcos was a Landing Ship Dock that carried three LCUs (Landing Craft Utility) and four LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicles, Personnel). San Marcos had sailed from Vieques Island. At Point Zulu, the 7 CEF ships sailed north without the USN escorts, except for San Marcos that continued until the seven landing craft were unloaded when just outside the 5 km (3mi) Cuban territorial limit.[5][17][41]

Invasion

Invasion day (17 April)

During the night of 16/17 April, a mock diversionary landing was organized by CIA operatives near Bahia Honda, Pinar del Rio Province. A flotilla of small boats towed rafts containing equipment broadcasting sounds and other effects of a shipborne invasion landing. That was the source of Cuban reports that briefly lured Fidel Castro away from the Bay of Pigs battlefront area.[5][27]

At about 00.00 on April 17, 1961, the two CIA LCIs Blagar and Barbara J, each with a CIA "operations officer" and an Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) of five frogmen, entered the Bay of Pigs (Bahía de Cochinos) on the southern coast of Cuba. They headed a force of four transport ships (Houston, Río Escondido, Caribe, and Atlántico) carrying about 1,300 Cuban exile ground troops of Assault Brigade 2506, plus tanks and other armour in the landing craft. At about 01.00, the Blagar, as the battlefield command ship, directed the principal landing at Playa Girón (Blue Beach), led by the frogmen in rubber boats followed by troops from Caribe in small aluminum boats, then LCVPs and LCUs. The Barbara J, leading Houston, similarly landed troops 35 km further northwest at Playa Larga (Red Beach), using small fiberglass boats. Unloading troops at night was delayed, due to engine failures and boats damaged by unseen coral reefs. The few militia in the area succeeded in warning Cuban armed forces via radio soon after the first landing, before the invaders overcame their token resistance.[27]

At daybreak at about 06.30, 3 FAR Sea Furies, 1 B-26 and 2 T-33 jets started attacking those CEF ships still unloading troops.

At about 07.00, 2 x FAL B-26s attacked and sank the Cuban Navy Patrol Escort ship El Baire at Nueva Gerona on the Isle of Pines.[38] They then proceeded to Giron to join two other B-26s to attack Cuban ground troops and provide distraction air cover for the paratroop C-46s and the CEF ships under air attack. At about 07.30, 5 C-46 and one C-54 transport aircraft dropped 177 paratroops from the parachute battalion of Assault Brigade 2506 in an action code-named Operation FALCON.[42] About 30 men plus heavy equipment were dropped south of Australia sugar mill on the road to Palpite and Playa Larga, but the equipment was lost in the swamps and the troops failed to block the road. Other troops were dropped at San Blas, at Jocuma between Covadonga and San Blas, and at Horquitas between Yaguaramas and San Blas. Those positions to block the roads were heavily maintained for two days, reinforced by ground troops from Playa Girón.[13]

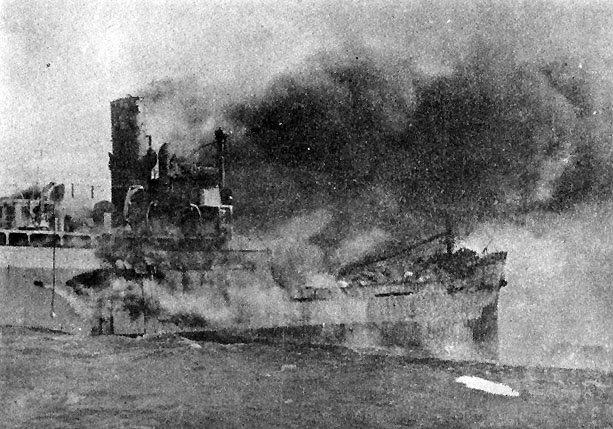

At about 08.30, a FAR Sea Fury piloted by Carlos Ulloa Arauz crashed in the bay, due to stalling or anti-aircraft fire, after encountering a FAL C-46 returning south after dropping Paratroops. By 09.00, Cuban troops and militia from outside the area had started arriving at Australia sugar mill, Covadonga and Yaguaramas. Throughout the day they were reinforced by more troops, heavy armour and T-34 tanks often carried on flat-bed trucks.[13] At about 09.30, FAR Sea Furies and T-33s attacked with rockets the Rio Escondido, that "blew up" and sank about 3 km south of Girón.[14]

At about 11.00, a FAR T-33 attacked a FAL B-26 (serial number 935) piloted by Matias Farias who then survived a crash-landing on the Girón airfield, his navigator Eduardo Gonzales already killed by gunfire. His companion B-26 suffered damage and diverted to Grand Cayman Island; Pilot Mario Zúñiga (the "defector") and navigator Oscar Vega returned to Puerto Cabezas via CIA C-54 on 18 April. By about 11.00, the two remaining freighters Caribe and Atlántico, and the CIA LCIs and LCUs, started retreating south to international waters, but still pursued by FAR aircraft. At about 12.00, a FAR B-26 exploded due to heavy anti-aircraft fire from Blagar, and pilot Luis Silva Tablada (on his second sortie) and his crew of three were lost.[16]

By 12.00, hundreds of militia cadets from Matanzas had secured Palpite, and cautiously advanced on foot south towards Playa Larga, suffering many casualties during attacks by FAL B-26s. By dusk, other Cuban ground forces were gradually advancing southwards from Covadonga and southwest from Yaguaramas towards San Blas, and westwards along coastal tracks from Cienfuegos towards Girón, all without heavy weapons or armour.

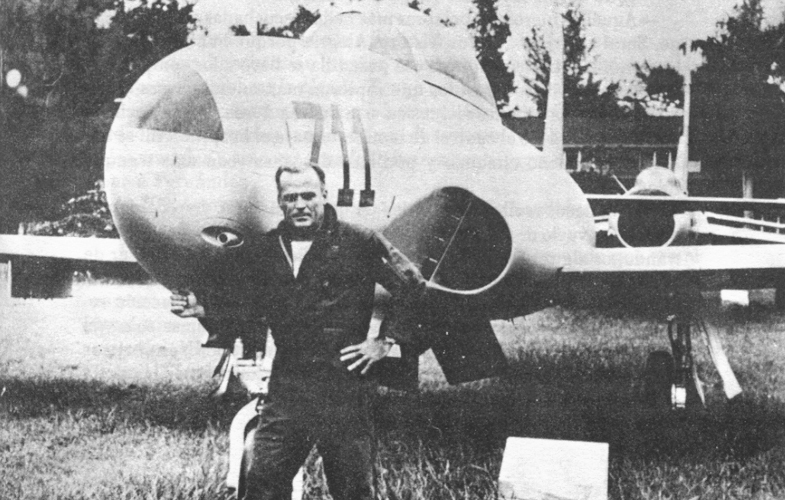

LT Del Pino by his armed T-33 Shooting Star

During the day three FAL B-26s were shot down by T-33s, with the loss of pilots Raúl Vianello, José Crespo, Osvaldo Piedra and navigators Lorenzo Pérez-Lorenzo and José Fernández. Vianello's navigator Demetrio Pérez bailed out and was picked up by USS Murray. Pilot Crispín García Fernández and navigator Juan González Romero, in B-26 serial 940, diverted to Boca Chica, but late that night they attempted to fly back to Puerto Cabezas in B-26 serial 933 that Crespo had flown to Boca Chica on 15 April. In October 1961, the remains of the B-26 and its two crew were finally found in dense jungle in Nicaragua.[38][43] One FAL B-26 diverted to Grand Cayman with engine failure. By 16.00, Fidel Castro had arrived at the central Australia sugar mill, joining José Ramón Fernández whom he had appointed as battlefield commander before dawn that day.[13]

On April 17, 1961, Osvaldo Ramírez (then chief of the rural resistance to Castro) was captured in Aromas de Velázquez and immediately executed.[44] The CIA was unaware or unconcerned at this repression's effects on the planned operation.[17]

At about 21.00 on 17 April 1961, a night air strike by three FAL B-26s on San Antonio de Los Baños airfield failed, reportedly due to incompetence and bad weather. Two other B-26s had aborted the mission after take-off.[16][40] Other sources allege that heavy anti-aircraft fire scared the aircrews, the resultant smoke perhaps a convenient excuse for "poor visibility".[13]

Czechoslovakian-made M-53 quad 12.7mm anti-aircraft machine gun

Invasion day plus one (D+1) 18 April

By about 10.30 on 18 April, Cuban troops and militia, supported by tanks, took Playa Larga after Brigade forces had fled towards Girón in the early hours. During the day, Brigade forces retreated to San Blas along the two roads from Covadonga and Yaguaramas. By then, both Fidel Castro and José Ramón Fernández had re-located to that battlefront area.[13]

At about 17.00 on 18 April, FAL B-26s attacked a Cuban column of 12 civilian buses leading trucks carrying tanks and other armour, moving southeast between Playa Larga and Punta Perdiz. The vehicles, loaded with civilians, militia, police and soldiers, were attacked with bombs, napalm and rockets, suffering heavy casualties. The 6 B-26s were piloted by two CIA contract pilots plus four pilots and six navigators from Assault Brigade 2506 air force.[27][38] The column later re-formed and advanced to Punta Perdiz, about 11 km northwest of Giron.[13]

Invasion day plus two (D+2) 19 April

During the night of 18 April, a FAL C-46 delivered arms and equipment to the Girón airstrip occupied by Assault Brigade 2506 ground forces, and took off before daybreak on 19 April.[45] The C-46 also evacuated Matias Farias, the pilot of B-26 serial "935" (code-named Chico Two) that had been shot down and crash-landed at Girón on 17 April.[42]

The final air attack mission (code-named Mad Dog Flight) comprised 5 B-26s, four of which were manned by American CIA contract air crews and pilots from the Alabama Air Guard. One FAR Sea Fury (piloted by Douglas Rudd) and two FAR T-33 (piloted by Rafael del Pino and Alvaro Prendes) shot down two of these B-26s, killing four American airmen.[17]

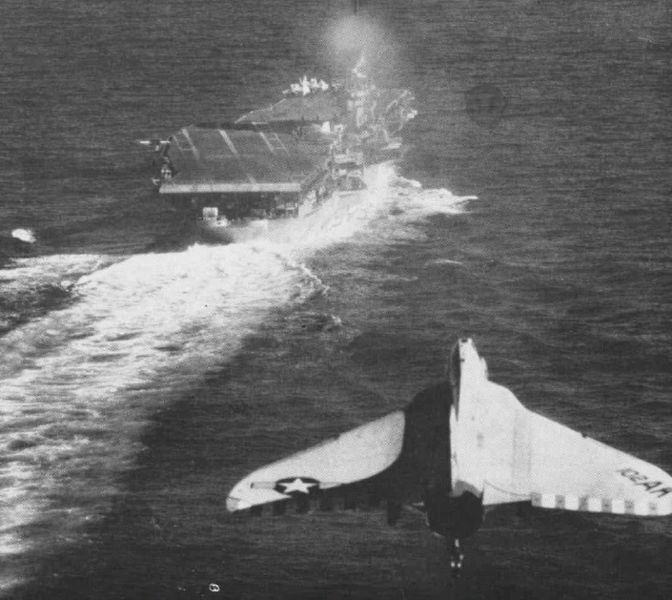

USS Essex

Combat air patrols were flown by Douglas A4D-2N Skyhawk jets of VA-34 squadron operating from USS Essex, with nationality and other markings removed. Sorties were flown to reassure Brigade Soldiers and pilots, and to intimidate Cuban government forces without directly engaging in acts of war.[38]

A section of A-4 SkyHawks

Without direct air support, and short of ammunition, Assault Brigade 2506 ground forces retreated to the beaches in the face of considerable onslaught from Cuban government artillery, tanks and infantry.[14][46][47][48]

Late on 19 April, destroyers USS Eaton (code-named Santiago) and USS Murray (code-named Tampico) moved into Cochinos Bay to evacuate retreating Brigade Soldiers from beaches, before opportunist firing from Cuban army tanks caused Commodore Crutchfield to order a withdrawal.[27]

Invasion day plus three (D+3) 20 April

From 19 April until about 22 April, sorties were flown by A4D-2Ns to obtain visual intelligence over combat areas. Reconnaissance flights are also reported of Douglas AD-5Ws of VFP-62 and/or VAW-12 squadron from USS Essex or another carrier, such as USS Shangri-La that was part of the task force assembled off the Cayman Islands.[27][38]

On 21 April, Eaton and Murray, joined on 22 April by destroyers USS Conway and USS Cony, plus USS Threadfin (submarine) and a CIA PBY-5A Catalina flying boat, continued to search the coastline, reefs and islands for scattered Brigade survivors, about 24-30 being rescued.[45]

Aftermath

Casualties

Aircrews killed in action totaled 6 from the Cuban air force, 10 Cuban exiles and 4 American airmen.[16] American Paratrooper Eugene Herman Koch was killed in action, and the American airmen shot down were Thomas W Ray, Leo F Baker, Riley W Shamburger and Wade C Gray.[27] In 1979, the body of Thomas "Pete" Ray was repatriated from Cuba. In the 1990s, the CIA admitted to his links to the agency, and awarded him the Intelligence Star.[49] 114 Cuban exiles from Assault Brigade 2506 were reportedly killed in action.[27]

Cuba's losses during the conflict are variously reported as 4,000 killed, wounded or missing [6], or about 5,000.[7] Cuban sources report over 2,200 casualties[50]. The final toll reported was 176 killed in action in Cuban armed forces during the conflict.[5] That number might be for Cuban army losses only, not including militia or armed civilian loyalists, so a total of around 2,000 (perhaps as many as 5,000, see above) Cuban militia may have been killed, wounded or missing in action. The 15 April airfield attacks left 7 Cuban dead and 54 wounded.[5]

Prisoners

On 18 April, 1961, at least seven Cubans plus two CIA-hired U.S. citizens (Angus K. McNair and Howard F. Anderson) were executed in Pinar del Rio province. On 20 April, Humberto Sorí Marin was executed at Fortaleza de la Cabana, having been arrested on 18 March following infiltration into Cuba with 14 tons of explosives. His fellow conspirators Rogelio Gonzalez Corzo (alias "Francisco Gutierrez"), Rafael Diaz Hanscom, Eufemio Fernandez, Arturo Hernandez Tellaheche and Manuel Lorenzo Puig Miyar were also executed.[6][13][24][35][51]

Between April and October 1961, hundreds of executions took place in response to the invasion. They took place at various prisons, including the Fortaleza de la Cabaña and El Morro Castle.[6] Infiltration team leaders Antonio Diaz Pou and Raimundo E. Lopez, as well as underground students Virgilio Campaneria, Alberto Tapia Ruano, and more than one hundred other insurgents were executed.[10]

About 1,204 Assault Brigade 2506 members were captured, of which nine died from asphyxiation during transfer to Havana in a closed truck. In May 1961, Fidel Castro proposed to exchange the surviving Brigade prisoners for 500 large farm tractors. The trade rose to U.S. $28 million.[8] On 8 September 1961, 14 Brigade prisoners were convicted of torture, murder and other major crimes committed in Cuba before the invasion, five being executed and nine jailed for 30 years.[3] Three confirmed as executed were Roman Calvino, Emilio Soler Puig ('el Muerte') and Jorge King Yun ('el Chino').[14][35] On 29 March 1962, 1,179 men were put on trial for treason. On 7 April 1962, all were convicted and sentenced to 30 years in prison. On 14 April 1962, 60 wounded and sick prisoners were freed and transported to the U.S..[3] On December 21, 1962, Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro and James B. Donovan, a U.S. lawyer, signed an agreement to exchange 1,113 prisoners for U.S. $53 million in food and medicine; the money was raised by private donations. On 24 December 1962, some prisoners were flown to Miami, others following on the ship African Pilot, plus about 1,000 family members also allowed to leave Cuba. On 29 December 1962, President John F. Kennedy attended a "welcome back" ceremony for Assault Brigade 2506 veterans at the Orange Bowl in Miami, Florida.[14]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Essex_(CV-9)

Bay of Pigs and Cuban Missile Crisis

In April 1961, Essex steamed out of Jacksonville, Florida on a two-week "routine training" cruise, purportedly to support the carrier qualification of a squadron of Navy pilots. 12 x A4D-2 Skyhawks had been loaded aboard. The pilots were from attack squadron VA-34 Blue Blasters. The A4D-2Ns were armed with 20mm cannon, and after several days at sea all their identifying markings were crudely obscured with flat gray paint. They began flying mysterious missions day and night with at least one returning bearing battle damage. Not generally known to Essex crew was that they had been tasked to provide air support to CIA-sponsored bombers during the ill-fated Bay of Pigs Invasion. The naval aviation part of the mission was aborted by President Kennedy at the last moment and the Essex crew sworn to secrecy.[1]

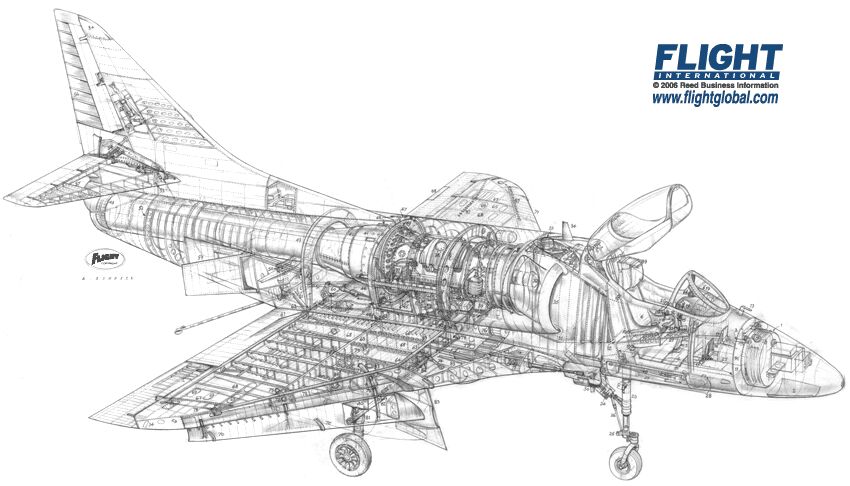

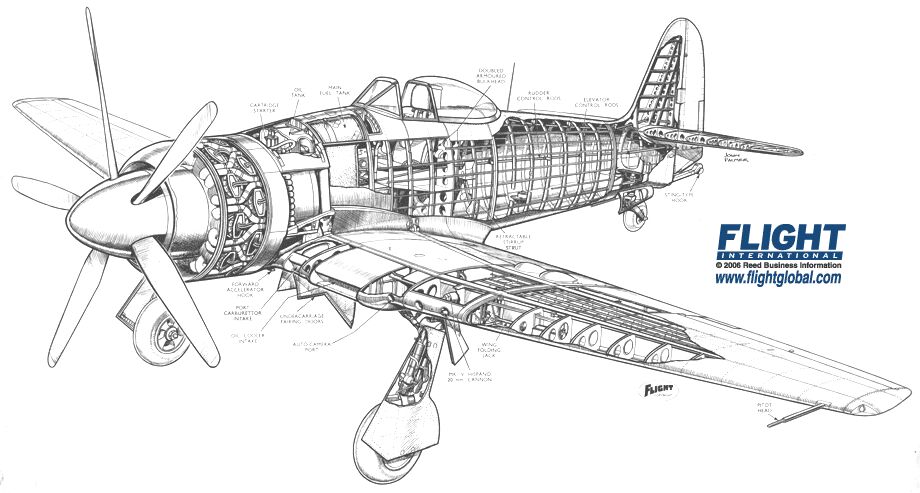

A-4 SkyHawk cut-away drawing

In the early-to-mid 1960s, standard US Navy A-4B Skyhawk squadrons were assigned to provide daytime fighter protection for ASW aircraft operating from some Essex class U.S. anti-submarine warfare carriers, these aircraft retained their ground- and sea-attack capabilities. The A-4B model did not have an air-to-air radar, and it required visual identification of targets and guidance from either ships in the fleet or an airborne E-1 Tracer AEW aircraft. Lightweight and safer to land on smaller decks, Skyhawks would later also play a similar role flying from Australian, Argentinean, and Brazilian upgraded World War II surplus light ASW carriers, which were also unable to operate most large modern fighters.[15][16][17]

20mm cannon in wing root of an A-4

Primary air-to-air armament consisted of the internal 20mm (.79 in) Colt cannons and ability to carry an AIM-9 Sidewinder missile on both underwing hardpoints, later additions of two more underwing hardpoints on some aircraft made for a total capacity of four AAMs. Only two confirmed A-4 air-to-air kills have ever been made, both with Zuni rockets designed for use against ground targets.

http://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=58&t=146060&p=1287947

reocities.com/urrib2000/Tanques3-e.html

M41 Walker Bulldog ...Five [light] tanks of this type formed the 4th Tank Battalion of the 2506 Brigade of Cuban exiled, that disembarks in Bay of Pigs on April 17, 1961. The M41 landed since barges LCU by Giron. They intensely fought, supporting the infantry, achieving to defeat 5 x T-34-85[s], together the recoilless rifles and the [2.36" and 3.5"] bazookes, until they were defeated, losing 2 destroyed and the remainder damaged or abandoned without munitions. Cuba send one M41 to the USSR, that was studied for the Soviets, and that today is exhibited in the Kubinka Museum of Moscow. Another are exibited in the Museum of Giron Beach.

globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/EJR.htm

The Bay of Pigs: A Struggle For Freedom

CSC 1984

SUBJECT AREA History

WAR SINCE 1945 SEMINAR

The Bay of Pigs: A Struggle for Freedom

Major Joe R. English

2 April 1984

Marine Corps Command and Staff College

Marine Corps Development and Education Command

Quantico, Virginia 22134

ABSTRACT

Author: ENGLISH, Joe R., Major, U.S. Marine Corps

Title: THE BAY OF PIGS: A STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM

Publisher: Marine Corps Command and Staff College

Date: 16 March, 1984

This paper presents a review of the invasion of Cuba in April, 1961, by a group of Cuban exiles. This invasion became known as the Bay of Pigs invasion because of the area where the landing took place. The invasion force was financed and trained by the CIA with the full knowledge and approval of the Executive branch of our government.

The operation was conceived under the Eisenhower administration as a guerrilla insertion. It was passed on to the Kennedy administration where it was expanded to the final product of a full-scale invasion by the brigade of exiles.